Illness, Metaphor, Wit

Hannah Dentinger reviews Susan Deborah King's "One-Breasted Woman" published by Holy Cow Press ($15.95). It's a deeper excursion than most into the context of this illness.

Susan Deborah King’s third collection of poetry centers around her experiences as a breast cancer survivor. In her preface to the book, she explains its division into three sections, Nigredo, Albedo, and Rubedo, terms Jung borrowed from the ancient pseudo-science of alchemy to describe the transformative nature of psychoanalysis. The journey of the psychoanalyst’s client (King herself has worked as a psychotherapist) is like the journey of the woman diagnosed with breast cancer: from fear and ignorance, through a necessary period of pain, to acceptance, and either death or renewed life.

This intriguing metaphor provides a frame for King’s writing, which varies from the intensely inward-looking to the more impersonal in her many fine nature poems. The collection begins with “Where She Can Be Found,” which functions as a sort of second preface and is a portrait of One-Breasted Woman, a symbolic figure that King says “visited” her while she was ill.

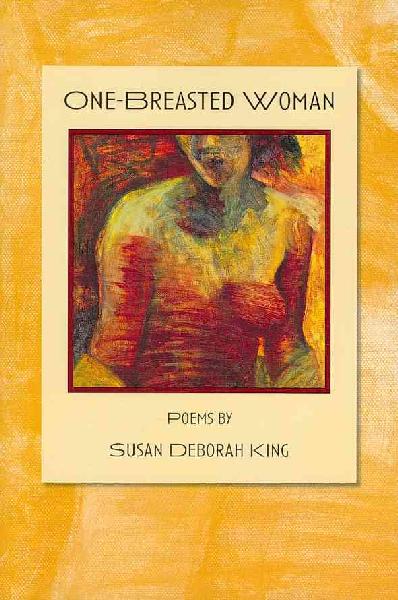

This poem, as well as the cover of the book with its colorful and impressionistic painting of a naked female torso minus one breast, are reminiscent of the type of New Age feminism that is best encapsulated by the popular poem “Warning,” by Jenny Joseph:

When I am an old woman, I shall wear purple

With a red hat which doesn’t go, and doesn’t suit me. […]

I shall go out in my slippers in the rain

And pick the flowers in other people’s gardens

And learn to spit.

Compare King’s One-Breasted Woman, “a lovely, lumpy, lopsided hag,” who

doesn’t care a stick anymore

how she, or anyone else, looks. […]

Down to her spreading hips falls

her wild, wavy gray mane,

yet she can be glimpsed at night

through candlelit panes trying on

ribbons and capes, enjoying jewels.

Although this aspect of contemporary women’s writing can be winning and may be empowering, it isn’t exactly original. However, as the book progresses, King’s individual voice quickly emerges and the reader is drawn into a companionable, humorous and wise presence.

Susan Deborah King has a keen appreciation of nature, and describes it skilfully, as in the poem “Passementerie,” which compares spring buds to sartorial frippery:

The trees are sprigged with mini-

gold-green pom-poms rah-rahing Spring,

hung with thousands of dangling tassels.

In “Tulips Dying,” a vase of flowers is ignored by a household too busy to look at them. They wilt,

their supple, slightly bended stems

sucking up darkening water in the vase,

soft green leaf spears arcing over the lip.

Their petals’ silken flesh dries and twists

to parchment, to husks. […]

It will be days before anyone notices

and in disgust absentmindedly tosses them

into dark plastic bags with moldy applesauce

to await the garbage truck’s uproarious jaws.

The surprise of these last lines, with their unusual half-rhyme (applesauce and jaws), provides a piquant contrast with the moody romanticism of King’s description of the wasted flowers. It is characteristic of her delicately ironic sensibility. King is at her best when, as in “Tulips Dying,” she combines psychological insight with close observation.

There is a sense of urgency in some of the poems in this book that does not always serve them well. An example is “Plastics,” a poem in which King is at pains to make her reader aware of the carcinogenic properties of plastics:

Did you know that softer plastics ‘gas off,’

release their toxins to whatever comes in contact

with them?

I feel that King’s eagerness to get her message across has worked against her here. Prose would seem a much more suitable vehicle for facts like these, which do not translate well into verse because it is a more unforgiving and concentrated form of writing.

Despite this tendency to over-explain, King has written some very fine poems about her battle with breast cancer. My favorite is “Boob,” which describes a prosthestic breast at humorous length, yet does not skirt the darker issues of trauma, fear, and self-doubt associated with having a mastectomy:

It looks like a sand dune, a mosque dome,

a homeless mollusk. It shape shifts in my hand

like silly putty, like a piece of meat in aspic.

When prodded, it jiggles. It’s a silicone hillock. […]

Still warm

for awhile when I take it off as I’ll be

for a few moments after I’m gone, it schlumps

faux-nipple down on my bureau making a basin,

a crater, a goblet top—the cup that wouldn’t pass.

King’s excellent ear for a memorable phrase is apparent here: “homeless mollusk” and “silicone hillock” are not merely evocative images—alliteration and internal rhyme make them catchy, too. And rare is the poet who casually alludes to the Bible while making a pun about her bra as in “the cup that wouldn’t pass.”

The preface to One-Breasted Woman informs us that a woman is diagnosed with breast cancer every 1.9 minutes. Most of us, sad to say, are aware of the prevalence of this disease—few lives have not been touched by it, if only peripherally. Susan Deborah King’s heartfelt collection of poetry is a testament to a struggle that belongs not only to her, but to millions of women and those who love them.