Host at Soap Factory

"Host," curated by Eizabeth Grady, is full of the damnedest things, or the things of the damned, or something. Its fun, though, and weirdly relaxing in its will to serious play while the tsunami hovers off shore. Through October 21.

Exhibiting artists are: Alejandro Almanza Pereda, William R. Bergman, China Blue, David Bowen, Tracey Goodman, Erik Shorrock Guzman, Wade Kavanaugh, José Enrique Krapp, Caitlyn Masley, Panayiotis Michael, Derick Melander, Jeffrey Morrison, Jason Peters, Meridith Pingree, Jenny Polak, David Politzer and Carol Salmanson

“Host” at the Soap Factory was curated by Elizabeth M. Grady of the Whitney Museum of American Art, and presents artists who think about the relation of individuals to various kinds of systemic structure or thought: whether that is biological or cybernetic feedback mechanism or the rough and ready futurist superman of self-help systems; or economic systems that sort and value people by productivity or mechanistic systems that dazzle us with their otherworldly beauty, fixing and holding our gaze.

The curatorial statement seems perhaps deliberately foggy; a show that presents the often malign beauty of hyperarticulated and overdefined systems maybe must avoid prematurely delimiting itself . . . or maybe wants to make the dubiety of its allegiance clear by being unclear?

Okay, so it worked on me. But how would you react to this statement?

“At the intersection between the private and public spheres we experience social and emotional tensions. Venturing into shared spaces, like the remarkable building and site of The Soap Factory, we may follow or resist pre-set paradigms of speech and behavior. The motion, interactivity, and participatory nature of the work in Host refers metaphorically to such daily choices, encouraging a heightened awareness of the impact of one’s actions on broader patterns of economic, political and societal relations.”

The statement goes on to disavow any advocacy for or against individuals or systems, and this is a blessing. There is no polemic here, and most works seem emotionally truthful about our exceedingly complex absorption into systematicity nowadays—often nodding toward humanness as at least partially defined currently by a kind of prosthetic machinery. This seems very postmodern, but of course one definition of humanness—human beings as the ones who use tools—has always accepted the tool, the add-on, the piece of technology, as part of our human bodies.

The way that the highly articulated works in this show recede before interpretation is very interesting: they don’t refuse to tip their hands; it’s just no one’s holding a royal flush or even a simple straight. No piece, even the really aggressive TV installation “Weight,” by David Politzer, manages any unambiguous stance on this massive infiltration of flesh and system.

In fact most of the pieces edge into humor, although, it is true, more or less dark (see the anarcho-terrorist kits built by Jose E. Krapp, “An Exercise in confession / the trouble with damage control; Or, The crew is getting restless,” and the Beckettian artist name really threads the screw, you know?)

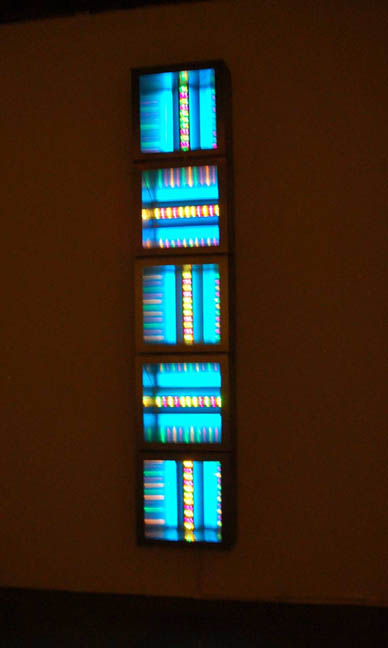

Some, though, are almost purely antic (like “Just Give Me a Place to Stand,” the rather amazing immense goofball structure held up with the menacing fragility of long lit fluorescent tubes stuck in water and balancing mirrors on rolling stools built by Alejandro Almanza Pareda, no more jerrybuilt than this sentence’s syntax), and some (Erik Shorrock Guzman’s “Lost Sense”) are dazzlingly and inhumanly gorgeous, like some kind of sex toy for highly advanced robots.

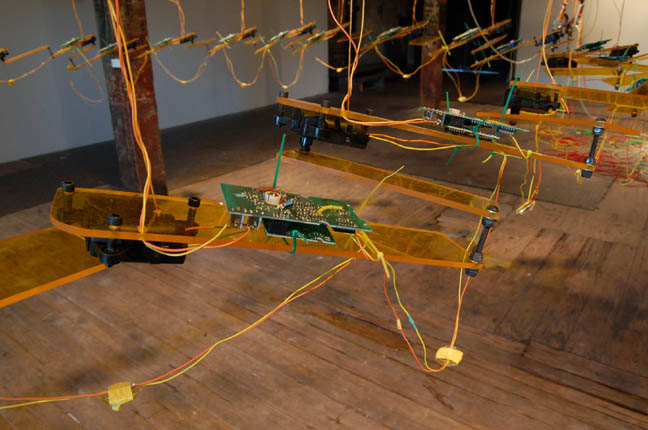

Meridith Pingree and David Bowen both do the sculptural equivalent of circuitbending, repurposing the circuitry of garage-door openers, toys, motion and light sensors, and other industrial debris including fishnet stockings, to create the illusion of living, perceiving creatures made of dreck. Bowen’s actually incorporate living beings (flies, bamboo plants) in the mix, reversing the machines-serve-life model into a life-serves-machine mode. But their weird semi-menace is completely undercut by the plaintively abortive quality of their movement, wallflowers at the dance of the living—or the lifelike.

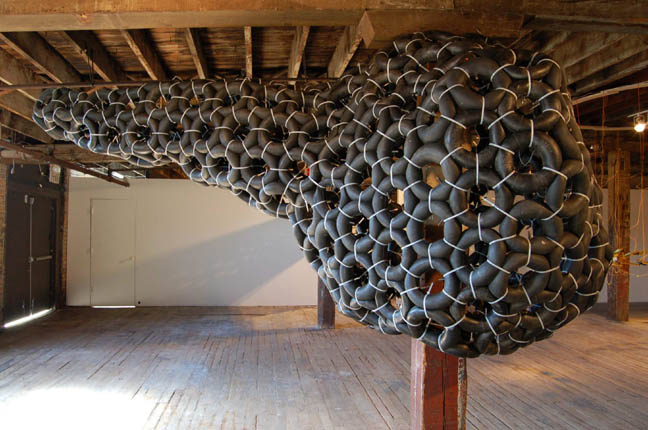

Caitlin Masley and Tracey Goodman both evoke the hive and the decay of cities, hypercomplex systems that often sag under their own weight, and crumple when nature’s skin ripples, or when the ocean casually rises and engulfs them.

There’s much more to see here, and it can’t be summed up; all I can do is designate Philip K. Dick the poet laureate of the world that this show seems to hint at, and recommend that you go see it for yourself.