History In Your Hands: Allen Christian’s House of Balls

Writer and performer Sam Osterhout offers a funny, engaging essay in response to the inventive work springing from the imagination of sculptor Allen Christian, the artist behind Minneapolis' House of Balls.

“…Oh, Bill, to know

everything! Look—the whole world is alive,

waving together toward history!”

—from At The Breaks Near The River by William Stafford

MY BEST FRIEND IN GRADE SCHOOL lived in an antique store. His mother converted the first floor of an old, small-town train depot into the retail outfit and the family lived upstairs. As far as I could tell, this endeavor wasn’t a labor of love—it was just a business. In Kansas, people have to be pretty creative to make a living. If they’re not farming, some people sell Amway, some raise Rottweilers, and some people fix things. It’s been this way forever. And Josh’s mom owned an antique store.

The shop may have been unremarkable to Josh and his family, but it was a carnival to me. Every corner was filled with oddities: hundreds of broken pocket watches; piles of old, sent postcards; portraits of strangers—wedding pictures, even; a rusted oil can; milk-crates full of rail spikes; two jars of marbles; a stuffed rabbit. I used to stand still in the middle of the room, just to avoid disrupting the debris. Josh and his sister, Annie, ran through the store heedlessly, like crazy people, stomping on old prairie quilts and plowing through piles of playing cards. The destruction of these artifacts didn’t suit my ten-year-old’s aesthetic. Josh and Annie, and their disregard for the endless piles of stuff, drove me cuckoo bird.

Each piece of Plains detritus in that store had some purpose in its origins. Every spike and playing card had been made and touched and had collaborated with its maker to fulfill that purpose. As a little kid, it seemed like my interactions with the junk in that antique store constituted collaboration by proxy. Just by standing in that room, I could talk to ghosts. And by destroying these relics, Annie and Josh were destroying my link to the phantoms of a long-past Kansas.

I was a weird kid. And Annie and Josh were clearly Philistines.

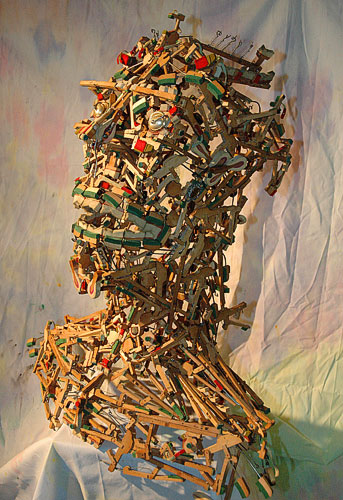

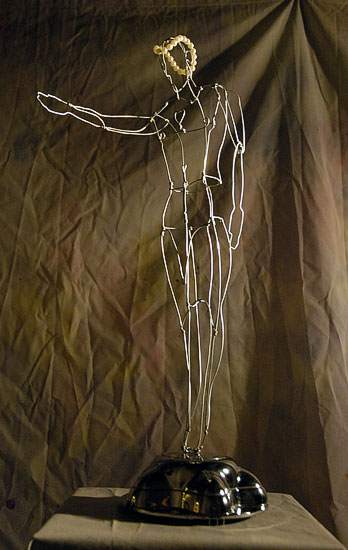

In early February as I walk into the House of Balls, a gallery-cum-storefront in downtown Minneapolis, I find myself standing among those ghosts again. The old oilcans, the rail spikes, the buckets, the barrels—they are all there; everyone I never knew come together again in junk. The floors and the walls and the ceilings and the stairs—all are covered with found objects, combined and sculpted into human figures. There are literally thousands of pieces—everywhere you look. It is like the antique store of my childhood, but the civil odds and ends in this place actually take the forms of the ghosts of their past, the makers with whom they once collaborated.

I am stunned and a little bit out of breath. I’ve heard about this place. Friends have told me that coming here is an experience, or that the work is eccentric and off-the-wall, but none of their descriptions really prepare me for what I find. I expected placards and artist statements and an artist with a sound sense of self-importance who uses words like schadenfreude.

Instead, I find Allen Christian and the universe he’s created out of things he’s found. Christian, the sculptor behind the House of Balls, makes connections for a living—he’s an electrician. When I meet him, he strikes me as soft spoken and thoughtful. I ask a question and he quietly stares straight ahead or up at the ceiling, or else he looks at one of his pieces; he answers carefully. Sometimes he disappears abruptly, and then reappears with one of his sculptures to illustrate a point. He comes back in the room carrying a bowling ball—one of his favorite mediums—sculpted down into a pair of lovers, or an aluminum plate die-cut into a face. I get the feeling that the House of Balls and each of its thousands of figures and oddities exists in his head precisely as it’s situated in the store. “Friends will come over and see that something’s missing,” he says, “and I’ll say, ‘I sold that piece two years ago.’” He’s got the place memorized.

Christian works his electrician job during the daytime hours. In the evening he makes his way to the House of Balls (“the storefront,” as he calls it) and begins sculpting. He says he makes at least one sculpture per day, some days two. By his own admission, he’s been called “uniquely bizarre,” a “curiosity,” and a “fucking freak.” Nonetheless, he’s been confusing and amazing people for over two decades. The House of Balls’ first incarnation was on 1st and Hennepin—another little storefront—for about eight years. The House has been in its current location for the last fourteen years and, judging by the amount of work on display, it’s been a busy fourteen years for him.

At House of Balls I feel like I’m ten again and in Kansas, standing in the middle of Josh and Annie’s antique store. But Allen Christian’s whirlwind of oddities is different in that he has purposely peeled away the layers of each object to reveal its story, or he has sometimes created a new story by combining disparate elements into a composite sculpture.

Christian is an animist. On his website, he declares, “I believe that the non-living thing acquires soul from contact with the living so that, with repeated use, a scythe takes on the spirit of the arm swinging it, the highway hungrily swallows the restlessness of those who traverse it, and a fence post longs for the wings of the crow that sits atop it.”

Unlike the old antique store, where an object kept its stories to itself, in House of Balls Allen Christian opens everything up for scrutiny. He forces the viewer to engage with the old stuff, to consider its history and the hands that have worked together to shape it. “Whether you make things or not,” he says, “you’re a part of the process.”

This is an idea that makes sense academically. People make things. People die. New people take care of the things the old people made. Therefore, people throughout time are linked through their things. Seems true. But when you spin the cogs and ding the bell of The Tabulator, a metal statue made from old typewriter parts, you really comprehend this truth. You have to run your fingers along one of the bowling balls that has been cut down to reveal an inner face, hold these things and manipulate them yourself. It’s only when you conspire with these oddities, contribute to the process, that you can feel the utter beauty of our collective human past.

Maybe I’m still a little weird.

I’ve never felt terribly connected to Minneapolis. I moved here to get married and then divorced. I have a car full of junk that I’ve collected along the way—folding chairs and picnic baskets and file cabinets and on and on. I don’t know what to do with it all. Toss it? Store it?

I shake hands with Allen Christian, that day in early February, and leave the House of Balls. I walk up to my car and look in. My junk is still there. I am suddenly struck with the image of all that stuff—my life in piles—reconstituted in some future Minneapolis antique store. Maybe there are some kids in there, maybe they live there. They’re running around the store like crazy people, kicking all of my old stuff. Their kicks collaborate with it—even the destruction of my stuff is collaborative—and, therefore, those kids collaborate with me. I look at my junk and can suddenly see my place in Minneapolis.

Allen Christian makes another connection.

About the writer: Sam Osterhout is co-founder of the Lit 6 Project and The Electric Arc Radio Show. His short stories can be heard on Minnesota Public Radio and in bars and bookstores across the country.

What: Midwestern Dandies: The Whimsy and Wit of Tom Stack, Chris Kerr, and Allen Christian

Where: The Fox Tax Gallery, Minneapolis, MN

When: Exhibition runs through April 30

Visit the website for gallery hours and detailed show information.