FILM: The Future of MN Film (Wherever You May Find It)

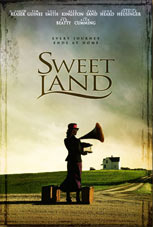

Ali Selim, writer and director of the acclaimed film fest favorite "Sweet Land," MPR's Euan Kerr, and web video creators Cristina Cordova and Juan Antonio del Rosario ("Chasing Windmills") talk about the future of motion pictures, wherever they may be.

Originally published on mnartists.org and in access+ENGAGE in July 2006.

WE HAVE BEEN STUNNED BY THE EXPLOSION of talent and innovation

that’s emerged in Minnesota in recent years, whether you’re talking about web video or traditional big-screen filmmaking. But at the same time, the local audiences for film seem to be evolving—some would even say

dwindling. We took our questions about the present and future of homegrown film to some news-making filmmakers and one of our favorite arts broadcasters: Ali Selim, writer and director of the buzz-worthy Sweet Land, a favorite at film festivals

(here and across the country); Cristina Cordova and Juan Antonio del Rosario,

creators of the Web video phenomenon Chasing

Windmills; and Euan Kerr, a Minnesota Public Radio news editor and one of

our favorite reporters on the movie beat. The conversation ranged far and wide—from the question of a “Minnesotan” film scene, to how the medium shapes the

story, to the looming concerns over the future of cinema as we know it.

Q: Have you run into

anything else like Chasing Windmills online?

Antonio:

There are some sitcoms, but nothing like what we’re doing, really (a daily, serialized fictional narrative).

Ali (to Antonio and Cristina): How do you make it all happen? How do you pay for it? How do you live?

Cristina:

Well, we’re not really making any money off of this right now. But,

theoretically, something like this could earn money through advertising.

Actually, what we’re leaning toward is product placement, because we already

have products in there. Chasing

Windmills, because it’s all about this couple’s daily life, is full of

products.

Antonio:

Everybody’s improvising. We’re still figuring out what to do with this new

medium. I see the New York Times multimedia

section changing formats regularly. Everyone’s trying to figure out “How do I

hold the baby?” I think it’ll take a little while for things to settle.

Euan: Do you think it really will settle?

Antonio:

I think a platform will develop eventually. The medium will mature and people

will try various things (and fail) until the Web develops its own conventions,

its own aesthetic.

Euan:

We’ve been going through this discussion at the radio station for going on ten

years. And we’ve got a much simpler format to deal with than you guys. First,

it was “we’re all going to satellite.” And then, “No, no,

nope. It’s definitely going to be… well, maybe not, the Internet.” [laughing]

Q: Ali, have you been making

use of the Web?

Ali:

Sweet Land’s website is ultimately for the

film festivals—they need images, press materials. It’s for 75 people really. If

other people come to the site, curious—that’s great, here’s a JPEG, download it

for whatever you want. What I’m really concerned with, though, are getting

butts in seats at the theater. When I dreamed of getting in this business (watching Mary Poppins and Flipper), I was dreaming of getting a

bunch of people in a room—all there to see my movie. That’s what I’m working

for.

Q: Will the movie-going

become a boutique experience only for true cinephiles, with the Web and TV

being the preferred method of watching films?

Ali:

Not at all… I think the same people who love their iPods will be saying, “You

have to see what’s showing down the block. It’s great…”

Antonio:

I agree. I don’t think people will want to lose that space. I don’t want to lose that space.

Cristina and I were speaking at a conference in San Francisco. We ended up talking about Lawrence of Arabia and screen size. Your

iPod’s great, but you can’t watch Lawrence

of Arabia on your iPod. Here’s the perfect visual story: you have that

great scene where Omar Sharif is arriving in the desert. On your iPod, when he

arrives you still can’t see him. Between the epic shot and the expanse of the

desert… on a screen that size, it’s just silly. You’re looking at empty space.

Ali:

And TV has adapted to the screen size, too. Television shows are mostly

dialogue, and they’re mostly close-ups. They figured out that wide shots just

don’t work on TV, and they adapted to the medium 50 years ago. Now we’ve got

these new media formats, and we’ll adapt to these

Cristina:

These different formats offer different experiences—they do different things.

Ali:

I actually have all of Sweet Land

on my cell phone screen. Let me get it. [Pulling out the phone and bringing up

the film on its screen.] There you go. All you need is a headset. It goes on

for two hours like that.

Euan:[big laugh] Have you watched it on there yet?

Ali:

No, I haven’t. But I gave it to someone at a film festival and he disappeared

with my phone, came back two hours later, and said he loved it. So, I guess he

didn’t mind the screen size.

Q: But don’t you think he

had a different experience, watching it on the phone, than you’d intended?

Ali:

A totally different experience. But I

think watching it on a screener at home is a totally different experience. We’ve

played the movie to sold-out houses (God bless) across the country, and there’s

such an energy in the room when you watch the movie that way. People play off each other in a theater; they know it’s okay to laugh from the others’ responses. It’s a very different experience.

Cristina:

We have to exploit something completely different than that for Chasing Windmills. For one thing, we have to deal with what people think of when they think of a “vlog,” which is

really me with my camera, showing you, “Hey, this is me eating breakfast.” That’s

what’s out there. We have to work with that. And why are viewers interested in watching

someone eat breakfast? Because it’s real people. The reason people go to these vlogs and read all this personal stuff is that they’re reaching out, sometimes in weird and

desperate ways for sure, but reaching out all the same for an experience of real people.

We’re

giving you that. You can sit there, by yourself, and look through a peephole

into my apartment. It’s fictitious, but we’re creating that

illusion for you. On that small screen of your computer, you want something

intimate. You want to be alone. It’s

not a joint experience, it’s a private one. It’s almost dirty. You’re looking

in on someone’s raw life—on the toilet, having sex, having arguments, personal

conversations. What we show people is really kind of ugly. It’s pretty dark

stuff. [laughing]

If

I were making something for the big screen, I would never make that. You need

to think about the medium you’re using. You can’t just take content intended

for TV or movies and throw it on the Web. It’s demeaning to the content. We had

a showing a while back, where a few of episodes of Chasing Windmills were shown on the big screen. I wanted to run and

hide under a table. It was horrible… it

was just awful. The images were never meant to occupy such a large space. Chasing Windmills is Web video—we’re not

intending to create a big-screen film.

Antonio:

You can shoot a film with your hand-held camera and not follow any rules of the

medium. And you can project it onto a wall. You can even call it a “film.” But

you’re not going to be using the aesthetics that work in that medium. And that does affect the story. On the Web, each

of our episodes needs to be self-contained. They need to exist by

themselves—with a beginning, middle, and end. There has to be some sort of

closure to each one. It’s a series, and each part needs to move the story

forward, but the Web requires instant gratification. There’s got to be some

sort of gag, something that holds it

together.

Euan:

I’m really intrigued by the question of where the audience is going. I’m

concerned about cultural literacy. You can fit lots of references into your

work, but if the audience doesn’t get it… when it’s for naught… If nobody’s

reading Moby Dick anymore, and if

they haven’t seen Gregory Peck, is it just going to be lost? [pause] I went to see Pirates

of the Caribbean with my son this week, and was infuriated by it. First of

all, it seemed to just lift things from other movies—for two and a half

hours—and there was a gimmick where the guy’s face moved around like an

octopus, but there was no story.

Ali:

It’s nice that it could infuriate you. I slept. [laughing]

Euan:

I keep hearing that people love it, but there’s no story there. And when you make it to the end, you find out it’s

not even really the end. “By the way, come back next Memorial Day for the rest

of the story.” The fact that people aren’t furious about that worries me.

Q: Ali,

now that Sweet Land has been received

so well, and you’re thinking of making more movies, does Euan’s concern about

audience expectations worry you, too? Do you worry that the audience for

thoughtful films is dwindling?

Ali:

[pause] From where I sit, my job is really to focus on

the story I want to tell and how to tell it well. Then I have to trust the

story—and that it will resonate with people, find its audience. If I start

worrying too much about making what people will like … I’d probably just end up making… Pirates of the Caribbean. [Everyone laughs] People ultimately want a good

story, well told. But, I think Alex and Malcolm [Ali’s son and Euan’s son respectively] might

think Pirates of the Caribbean is a

good story—the standards for that, the expectations of what that is, are based

around something different [more visual excitement.]

Q: Do you think the answer

will lie in niche filmmaking?

Antonio:

That’s happening already. There are all kinds of different cinematic

experiences to be had, depending on what you’re looking for. And, really,

fragmentation of the market is the best thing that can happen to writers. Fewer

multi-million dollar payouts, but more writers will be able to live

comfortable, middle-class lives making a living at it. The best thing about the

Web is that you can harness an audience internationally who, collectively,

could ultimately mean a significant market for your work. All of a sudden, lots

of filmmakers who couldn’t make it in the current system, actually have a shot

at doing something profitable. You’re talking about a whole new medium, where

filmmaking becomes like painting.

Euan:

The downside of this though, is that with a lot of people making movies, a lot

of them are going to be just terrible. It’s tough for the consumer to wade

through them. I wonder if it really would be easier to break in and get

noticed. You can make movies, but will anyone watch them?

Cristina:

I think there’s a tight, pretty incestuous group of people on the Web who

really check out what people are coming out with. When they saw Chasing Windmills, they loved it and

wrote about it on their pages, and linked to it. I think our audience found us

that way, by turning to those people as a way of wading through the traffic. It

got around in ripples like that—and since there’s really nothing else like it,

people have been all the more enthusiastic about what we’re doing. I’m not sure

about all the reasons why, but Chasing

Windmills got attention.

Q: When it all shakes out,

do you think people will still go out and see movies in a theater?

Antonio:

I don’t like going to the movies. I end up uncomfortable. I’ll undoubtedly have

to pee in the fourth act, so I’m always missing a chunk of the important part

of the film. I find it an increasingly unpleasant experience. And, God forbid, I

get someone laughing in the wrong place, or talking. Then I’m just miserable.

Most of the time, I’m more comfortable watching movies at home, and with bigger

and bigger TV sets and better sound and all these things that can simulate the

theatrical experience… I’m not a teenager and I don’t need to get away from my

parents. I’d just rather watch from home—going to the theater loses out to that

most of the time.

Cristina:

There’s something else going on, too. When I go to the movies and after sitting

through that discomfort, I’m mostly disappointed. I end up just frustrated.

Most of the movies that I see that I really like, I end up renting, either

because I didn’t make it to the theater in time or didn’t know to look for it.

I’m sure if I’d made it to the theater to see Munich or Syriana

I would have gone home pleased. Unfortunately, the last movies I made it to

the theater to see were big Hollywood

pictures. And afterwards, I just ask myself, “Why do I still do this? I have

problems with my lower back, and it’s painful.” [aughing]

Maybe if I just picked the right movies

to see in the theater… But how do you know?

Ali:

Cristina makes a good point. If the last ten films people saw in the theater

changed their lives—if the movies really mattered to them—they’ll keep going to

the movies. If they make the effort to go out to a theater and they’re

consistently disappointed, they’ll stop coming. I think there are lots of

things to do besides go to the movies—it really comes down to the story.

Filmmakers need to do their jobs well, focus on telling their stories the best

they can. If they do that, I believe the audience will be there. But it has to

be worth it.

Q: What do you make of the

troubles the Oak Street Cinema’s been having? Beyond sentimentality, is there a

real film community ready to actively support cinema in town?

Euan:

I wonder if there really is a Minnesotan film scene. I think there may have

seemed to be some kind of cohesive scene in the past,

because people would get together to make a movie (even if it was Jingle All the Way or some monstrosity

like that) and they’d meet and talk about what they were doing. Then they’d

make enough money to go off for three months and make something worthwhile. Now,

I don’t know if there really is a film community here…

Antonio:

I think it’s great that people arguing for it and trying to save it, but at the

end of the day, they’re not really showing up to watch movies there. Nostalgia

comes cheap.

Cristina:

I think it goes beyond just nostalgia. It’s about wanting

to preserve something—even if you’re not really using it—because it is important. I followed the whole

situation online and in print, but I didn’t show up to watch films or go to the

meetings. Antonio, I don’t think we’ve been to the Oak Street once to see a movie since last

August. And film is important to us. But even though we’ve not really done our

part to support it, it’s valuable to me to know that it exists.

Antonio:

It’s unfortunate, but there it is. I love that there has been someplace where I

can go and see Birth of a Nation on

the big screen. It’s a hell of a luxury, and I want it. But are there enough

people who are going to show up for enough pictures there to pay for keeping it

around?

Cristina:

When we first moved here, we went straight to IFP Minnesota. We paid our dues,

joined up, and offered to volunteer our time… But it’s amounted to nothing

really. On the other hand, when our work was shown at the Bryant Lake Bowl and as

word has spread about it online, all kinds of people came out of the woodwork.

There has been an incredibly supportive community of people to emerge, even offering

the use of equipment. But it’s not organized through anything like IFP. The support we’ve gotten has developed out of

relationships from people who’ve seen the series and spread the word. I do

think there are people looking to create a community—they’ve just not organized

themselves.

Antonio:

I do really appreciate the fact that here, instead of talking about creating something, I get the feeling that all kinds

of people are just quietly doing it.

A ton of really talented people in Minnesota are devoting themselves seriously to telling stories. There is far more respect

and encouragement for the independent voice here—an encouragement to find your

own voice and your own rhythm and to do that. And that’s unique about the

creative environment here. Nobody’s looking at you, you don’t need to posture

or talk about it—just shut up and find a quiet corner to work. Do something.

Special Features Section:

Media Recommendations from Euan, Ali, Cristina, and Juan Antonio

Euan:

I was handed a copy of A Sunday in Hell, I’d never

heard of it. It’s about a bike race, a foreign film from the ’70s. Beautiful,

French agricultural trails—it’s an amazing story. It’s not even really about

bike racing—it’s much more than that. I loved it.

Ali:

It’s one of my favorite movies. It’s scored with a mournful cello throughout… amazing. Just a wonderful film.

Euan:

Also, Road to Guantanamo. It’s just come out, and I think people should see it

just so they can talk about it. The movie centers around interviews with three

British guys who did some really stupid things and ended up in Afghanistan on

a lark. They were arrested, almost got themselves killed, and finally were

shipped to Guantanamo. Michael

Winterbottom, the director, intersperses those interviews with recreations and

actual footage shot from what was going on in Kandahar. The film’s manipulative and really,

really effective. [laughing] I finally saw Jules et

Jim which is out on DVD. That’s also an incredible piece of

film, and the extras on the DVD are really good.

Antonio:

I keep rereading The

Art of War.

Cristina:

He’s trying to internalize it. [laughing]

Antonio:

It’s true, I am. But I’m finding that as I read it, it calms me down. So

there’s that. And here’s a film that’s affected me lately—but it’s not good. I

watched Spielberg’s Munich recently, and I

became enraged. Spielberg is really a master of his craft now, and it’s cool to

see his mature work. But I came out of the film feeling almost like I had

watched something as bad as a Nazi propaganda film. It’s very effective, but

under the surface the message is horrible. In Munichthe Jewish people get the luxury of a

guilty conscience, and the Palestinians don’t. So, what am I walking away from

here? The Jew is human dealing with real internal conflict, and the Palestinian

is an animal without a conscience.

I don’t think I would have had such a violent reaction, but I watched Spielberg’s

introduction to the DVD (which in itself is a pretty pompous thing to include)

and that killed it for me. He said something I think all of us as filmmakers

can agree with, “The only tool you have as a filmmaker is empathy.” He said

that he was really just trying to empathize with what it’s like to do something

and have to live with the consequences, to understand. So, I’m with him at the

beginning, my hopes are up. And then I saw the film. What happened? What a

hoax!

I’m

pontificating in my head, I’m chain smoking, and I can’t stop thinking about

it. But there were all these things I

really liked about the film too, so it’s not that simple. It’s been a long time

since a movie has really gotten under my skin this way, so that’s something. As

a viewer, I felt cheated. Some day, I’ll tell you about my reaction to Saving Private Ryan…

[laughing]

Cristina:

L’Avventura. It’s the most

beautiful use of silence that I’ve ever seen anywhere. There’s a vlog called 90

Seconds of Dave. He did a narrative series,

15 episodes, and I think it’s absolutely beautiful, it’s art. I love the

way he mixes media—video, images, text. It’s just beautifully done.

Ali:

I really liked Man Push Cart. And

I liked The Syrian Bride—they took

this horrible Middle Eastern crisis and made something really human out of it.

I appreciated that.