Featured Artist: Alison Gerber, Fellow Traveler

Alison Gerber is this month's Featured Artist. Each month a different mnartists.org member artist will be chosen as the subject of an in-depth article. We hope you enjoy this look at the range and variety of the artists to be found on the site.

According to Alison Gerber, the pinnacle of the Walker’s recent “Everyday Design” show is a piece by Michael Anastassiades: the Anti-Social Light. Installed in an otherwise empty room, the ceiling-mounted fixture is the space’s sole source of light, and is notable for being sensitive to sound, so that it dims or completely darkens when you create atmospheric noise or talk. The Anti-Social Light thus seems to create an imperfect setting for conducting an interview – but here, it’s appropriate. For not only is the Anti-Social Light currently Alison Gerber’s favorite piece of art, but it also gets her talking about many of the issues that shape her own prolific artistic practice.

A photographer whose work has increasingly taken on aspects of performance and conceptual art, Gerber — raised in Inver Grove Heights, schooled at the University of Minnesota, and currently calling Minneapolis home — has been busy in past months; among other things, she undertook a residency in Trondheim, Norway, co-curated (with Jan Estep) the Soap Factory’s “Make it Real” show, and realized a Jerome Foundation “Inside/Outside Space” commission at Intermedia Arts. Her latest public art piece, Hostel, is currently in progress. All of these projects have reflected her fascination with orchestrating the experience of certain kinds of space and with casting those who encounter her art into a participatory, critical, role. Not unlike the Anti-Social Light, which she describes as “just an ordinary object that forces you to respect it and to adjust your behavior to it,” Gerber’s subtle and cerebral work alerts its audience to their often implicit relationships with spaces, places, and other people. Most importantly, it extracts from spectators a commitment to explore their own possibilities for action.

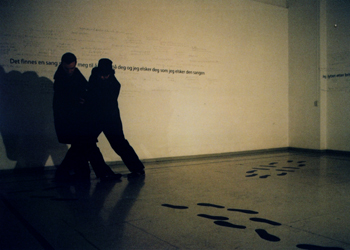

One intriguing experiment with such potentials was her Vil natten vare evig (Will the Night Last Forever), an event hosted in Trondheim on Valentine’s Day of 2003. The installation plays with the spatial configurations of a dancehall, aligning a row of chairs in formation along one wall and piping a sonic loop into the space. On the walls were printed texts in Norwegian concerning love; on the floor two large squares were marked, each containing step diagrams for unspecified dances. One square contained dance steps only for a solo participant. The room was, Gerber recalls, “a rather — no, a quite — uncomfortable space,” but it nevertheless succeeded in “making people interact in ways that were acceptable to me” and literally moving them in space.

“Can I make people who don’t know each other dance together?” she asks. “It was maybe a cheesy thing at best. But half, or maybe two-thirds, of the people would try out the steps. People danced, and people helped other people dance, moving their feet on the floor with the steps, people who didn’t know each other asked each other to dance. I liked this idea of art as a way to instigate or change social situations.”

In a more indirect fashion, her piece Informations in English, conducted in and around Reykjavik, Iceland in 2002, mediated the contributions of participants in what turned out to be a loose conversation about national identity. The piece involved small placards posted for one month at tourist sites, each one beckoning visitors to call a telephone number — Gerber’s cell phone — for more information about the site. Each caller was then asked to also contribute some information of their own about the site, and those contributions were mixed in and redistributed to subsequent callers. “At the beginning I was thinking about information as the material of the piece — about the way people have and use information, and shape the way other people think about their surroundings,” she says, noting that the information she gathered suggested wildly diverse interests and motivations. “I think you would call up to check on the representation of your nation; there was a lot of pride. But everybody also had a story or a personal relationship to the landmarks in the city” — including gossip about a certain guy who was remodeling his kitchen or about Donald Judd’s distaste for the design of the National Gallery of Iceland.

As the response to Informations swelled, Gerber found that its initial premises about information were complemented by the piece’s unforeseen character as performance — the piece was actually having an impact on how she lived her own life. “I underestimated the calls,” she explains. “I had declared that I was going to carry all these files around and answer the phone whenever it rings, on the assumption that nobody would call. I committed, and set myself up for it, and — hauling this bike bag full of stuff, having to duck into the toilet at the bar to take a call — the result was that it constantly made me think about what I was doing all the time….I understand how religious ritual works now.”

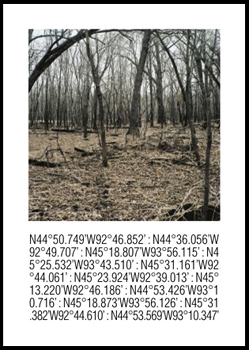

While Informations in English was essentially a piece about the multiplicity of viewpoints — as the unexpected “s” in the title seems to suggest — certain of Gerber’s works instead target a particular way of seeing. This is the case for her works directly confronting the practice of tourist photography, including Picture Yourself (her Jerome installation piece this past spring), which juxtaposed her own images with lists of global positioning sites in prints and on postcards distributed at sporting goods stores and state parks. The idea was that one equipped with a GPS system could potentially track down the points indicated on the card and make what Gerber refers to as “a perfect 19th-century landscape picture with a perfect frame and a vista.” Yet the effect of the piece goes beyond that of its antecedents, which for the most part aimed merely to produce visually appealing derivatives (among these antecedents are the old Kodak “Photospots,” which designated particularly photogenic sites for tourists, or the perennial camera club advice to model one’s photographs after a postcard of the site). Instead, Gerber argues that Picture Yourself, along with an earlier work of hers called Surrogate, seeks to share a critical, technical, and visual vocabulary with participants in the piece. “People are going to photograph things that should be photographed,” she says, referring to the conventionally beautiful fodder of tourist photography. “But I want some thought given to how you portray your own experience within that.” In Picture Yourself, the blunt instrumentality of the GPS data — the reduction of landscape to a functional set of numbers — makes “beauty” accessible, or at least findable, at the same moment that it renders its basis in convention transparent.

A public project in Chicago this summer sought a similar effect, posting photographic pointers to tourist photographers at thirteen sites around the city. The matching signs give little suggestion that they are part of an art project, appearing, because of their unified design identity, to be some sort of city or parks initiative. Given Gerber’s interest in sharing a technical or critical vocabulary with spectators, it is curious that in this case the pieces gain their authority by speaking a bureaucratic language instead of an art language. (This was also the strategy in the placards of Informations, as well as a piece called Contact, installed at the Soap Factory in 2002: there, an innocuous rack of cards bearing contact information for gallery staff used the gallery’s fonts and mission statement to legitimate its solicitation of visitor feedback.) It is precisely here that the most interesting contradictions opened up by Gerber’s work are manifested; the work opens the basic and nagging question about the function of this thing we call art. For it is precisely the occasional unrecognizability of Gerber’s work as “art” that enables it to have its effect.

“If you want something to function in space it has to speak a language other than an art language…if it’s the latter you come to it as art first and reality second,” she says. “People assume that art must be a comment on what’s happening, instead of art itself actually being something happening. If I just wanted to make some kind of commentary then I can do that through art,” she continues. “But if I want to change things, then I have to actually get people to think about what is possible.”

Gerber’s current piece, Hostel, does indeed promise to provoke both thought and action. Hostel involves the distribution of small litho tabs (like a museum admission badge) to hundreds of art world people from around the U.S. and abroad, among them many who have hosted Gerber in her travels or who have themselves similarly benefited from the generous hospitality of others. To wear the badge is at once to signify membership in a virtual community, but it also comes with a commitment — those who sport the insignia are duty-bound to “host” other badge-wearers. A community member who spies the “Hostel” logo on someone’s bag or lapel is entitled to request accommodation, support, and resources from the wearer. The import of Hostel is obviously practical – it’s about finding a safe haven in an otherwise alien place, and Gerber is currently developing a complementary administrative apparatus to facilitate the work of transient public and relational artists. But Gerber stresses its symbolic power; it’s “a way for people to assert their belief in the importance of the movement of young, unestablished artists,” a means of inscribing a potential artistic community within a contemporary world that is increasingly mobile and transient. Like so many of Gerber’s works, Hostel fuses design, performance, and concept to simultaneously comment on the situation and provoke people to think of how they might intervene in it. “Art seems a representation of reality and not reality: this is the assumption,” she explains. “But art can function as real life now.”