Farm Accident: A Secret History

Andy Sturdevant investigates the elusive history of Farm Accident, an ephemeral art gallery which lay at the center of the disco era's elite Minneapolis contemporary art scene, notorious for illicit, star-studded exhibitions in the IDS building downtown.

“IT WAS SLUMMING IN REVERSE,” says Rachel Haselbauer over email, recounting her days as a gallerist in the art space she ran with her husband for four years, between 1979 and 1983. “By day, we were living in a tiny walk-up in Stevens Square, sharing a bathroom with three other families. By night, though, we’d be forty stories up over downtown Minneapolis, right in the middle of the financial district. You could see out the windows – they faced east – and the whole city was laid of in front of you, the capital, the Cathedral. It felt like we owned all of it. That was how Farm Accident felt.”

Farm Accident was an alternative art space, improbably (and illegally) located in an abandoned suite of offices on the 46th floor of the IDS Center between 1979 and 1983. If you were a well-connected artist in Minneapolis in the early ’80s, this is undoubtedly sounding vaguely familiar. Jenny Holzer, Robert Mapplethorpe and David Byrne all made appearances in the space while visiting Minneapolis, as did New York journalist Glenn O’Brien, who featured it on his infamous TV Party talk show in 1981. More importantly, Farm Accident also exhibited the work of at least two dozen other very ambitious Twin Cities artists in those years. The space was intentionally flooded on at least two occasions and filled with sand on one other.

Many other art spaces during this period existed on the margins of legality, but Farm Accident’s situation was unique. As Haselbauer suggested, theirs was a reversal of the usual formula by which underground galleries operated: by necessity, the space did its business in secret from the poshest address in the city. Openings were rarely publicized and even less frequently written about; exhibitions were known only to a handful of artists, Walker employees, MCAD faculty, musicians and hangers-on.

I first heard about Farm Accident two years ago, when I began researching the history of The Soap Factory and No Name Exhibitions for a show I was curating there. People spoke of it in mythical terms, like an outpost of the Lower East Side, floating up in the sky: Farm Accident, the no-holds-barred art space where the openings began at one A.M. or later, and you could only enter through a service elevator. And in the IDS Tower, no less.

In piecing together the story of the early Warehouse District scene from which No Name emerged, the name always came up. My interviewees would invariably lean forward, and ask “Have you heard about Farm Accident yet?” I’d say yes, I’d heard about it, but no one seems to have been there themselves. This was always the case: “Oh, I never went personally – I’d always hear about the shows later. But I have a friend who showed there; see if you can track him/her down…” Eventually, I just lumped Farm Accident in with venues like Medium West or E. Floyd Paranoid, other local galleries and spaces seemingly lost to history.

I abandoned the effort to find out more because — despite fantastic rumors of A-List names, raucous openings and other hazy, grandiose reminiscences — there was no real reason to believe Farm Accident wasn’t completely lost to history. First of all, oral history is all I had to go on. People had heard of the Haselbauers, but no one claimed anything like a friendship with them. Plus, besides a few passing mentions in the Twin Cities’ most faithful chronicler of the 1980s art scene, Artpaper, the only substantial print reference to Farm Accident that I can find anywhere isn’t even from a local paper: it’s just a few sentences in a profile on our local art scene by Grace Glueck, entitled “ART: In the Heartland, New Voices Emerge,” published in the March 3, 1982 issue of The New York Times. “Over forty stories up in the Phillip Johnson-designed IDS Tower, the elite of the Minneapolis art scene gather in a suite of abandoned law offices where they will revel until morning…” And that’s it. Glueck doesn’t say if she visited it herself, but there it is. And other than that, there’s complete media silence on the issue. Nothing in the Strib, nothing in the Pioneer-Press, nothing in the Twin Cities Reader or Sweet Potato/City Pages or anywhere else.

It was not until The Soap Factory show closed that I was able to take some time to put the pieces together. I finally managed to shake the names of “Rachel and Eric Haselbauer” out of a noted Minneapolis painter who’d been neighbors with them in Stevens at the time, but had since lost touch. Getting a hold of them took a lot of phone calls and email, but more on that later.

Eric Haselbauer and Rachel Saliterman met as students at MCAD in 1974, the year they graduated. She had grown up in St. Louis Park and earned a BFA in painting; he was raised in St. Paul and earned his degree in sculpture. The two of them got married after a quick courtship and lit off for New York City to live “in the cliché hovel” on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. There they spent a few years working on art, socializing, making friends with the denizens of the New York scene. In late 1977, Eric’s mother fell ill and, being out of money anyway, the couple returned to Minneapolis to take care of her.

“We wanted to do something big,” says Rachel. “It was disheartening to be back home after being in New York, so we had lots of grand ideas about what we could do.” The ideal project became apparent over the course of a few meals with Rachel’s family.

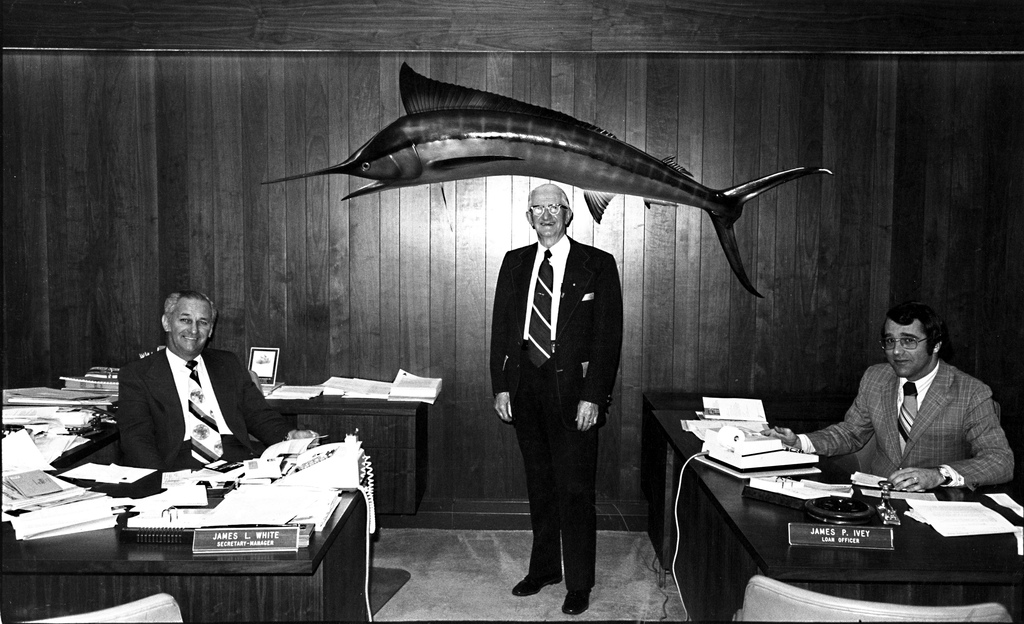

Rachel’s uncle was an affable commercial real-estate broker, named Bill Christensen; he was in charge of several properties downtown, including some spaces in the IDS. He had prospered in the building boom of the 1960s and was a lover of the arts – he collected work by contemporary artists (reputedly, he was the first Minnesotan to own a Basquiat painting), and had, in fact, helped his niece through MCAD. The IDS space had gone through a few tenants in the early ’70s, most notably serving as the offices of Petersen, Brenner and Kaplan, LLC, a law firm specializing in class-action lawsuits against manufacturers of farm equipment. When the law firm moved their offices to a less expensive address in the western suburbs in 1977, the space sat vacant for a year.

________________________________________________________

‘You know, there is a space that just opened up that might be interesting…’

And of course, he was talking about the IDS.“

________________________________________________________

“We’d been talking to Bill about how we’d wanted to open a space, and knew he had a great line on the real estate market,” says Eric. “Bill was always very supportive; he’d always asked us when we were in New York what art we’d seen. So, he was sympathetic.”

Rachel continues: “This one night – and this would be early in 1978 – we’re out at this dumpy Italian place in Richfield, Anzevino’s, and we’re all talking about real estate and where might be a good place for a gallery. And Bill gets a sort of gleam in his eye, and says ‘You know, there is a space that just opened up that might be interesting…’ And of course, he was talking about the IDS.”

Things moved quickly from there. Eric and Rachel saw the space and thought it was perfect. “We loved the hubris of operating in the IDS. It seemed so ridiculous,” says Eric. The space would be available after hours only, and only accessible through a freight elevator.

“Bill was just about to retire, I think,” says Rachel. “And he was always kind of a punchy guy, punchy old Uncle Bill. Working out of a vacant office suite, illegally, was just the kind of thing he thought would be a great laugh, a great joke.”

Dubbing the space “Farm Accident” in honor of its previous tenants, Rachel and Eric began working out the logistics. The only means of entry was a freight elevator, since the main elevators were closed down overnight; and the elevator was only accessible from the adjacent parking garage. On nights when there was to be an opening, Eric would have to stake out the garage, wearing a custodial outfit so as to move through the building unnoticed. After dark, he would shuttle in Rachel and any artists, and after midnight he paid off a regular coterie of custodians “with cigarettes and twenty dollar bills” to guide partygoers in through the freight elevator, three or four at a time, in total silence. “It was like Man on Wire,” laughs Rachel, referring to the recent documentary on the French aerialist who snuck into the World Trade Center to perform his own art. “I saw that film and it took me right back.” In the morning, the revelers would have to be snuck back down. Unconscious or sleeping gallery goers were often carried out in tarps or crates by Eric and an accomplice, dressed in custodial gear, to avoid suspicion. One prominent New York sculptor was carried out in this way, and dumped near Moby Dick’s on Block E, until he woke up several hours later.

The logistics of this arrangement dictated, of course, that Farm Accident only show work in three or four exhibitions a year – but the ones they opted for were remarkable for their sense of derring-do. Rachel and Eric were careful to always choose regional artists they thought could handle such a unique space and whose work lent itself to easy, ephemeral, high-concept installation.

The names of the artists who showed at Farm Accident are faintly familiar to most Minnesota arts lovers: Russ Kaudy, Sandra Dwyer, Diane Sheehy, Bruce Boulger. Boulger paid tribute to the unusual gallery space with a 1979 piece called Presence, wherein he filled the rooms with helium and Christmas lights composed of bulbs hand-painted with purple watercolors – “the story was you could see this purple glow from anywhere downtown or in the Warehouse District, kind of like a Bat-Signal for artists.” For his show, Kaudy procured a collection of Minneapolis Police Department uniforms and Minnesota North Stars jerseys and stitched them into a long fabric roll with which he wrapped the entire room, in a piece entitled Thin Green Line/Thin Blue Line. Sheehy’s exhibition, crisiscrisiscrisiscrisis, consisted of tiny figurines made from plasticized petroleum, buried in mountains of sands for gallery goers to sift through and find. The sand was painstakingly brought up to the space, over the course of two weeks, in wooden crates by Eric and Sheehy. Dwyer’s show consisted of some of her Super-8 short films projected on each wall – one of these, May I Borrow Your Husband?, was shown in the Whitney Biennial in 1984. Each of these exhibitions was documented on 35mm film and with Polaroids, dismounted immediately, and that was the end of it.

________________________________________________________

The parties they told me about were fascinating; a who’s-who of the Carter-era

Minneapolis art scene, with an odd splash of out of town visitors,

bleary-eyed late-night revelers and anyone else who was able to talk their way in.

________________________________________________________

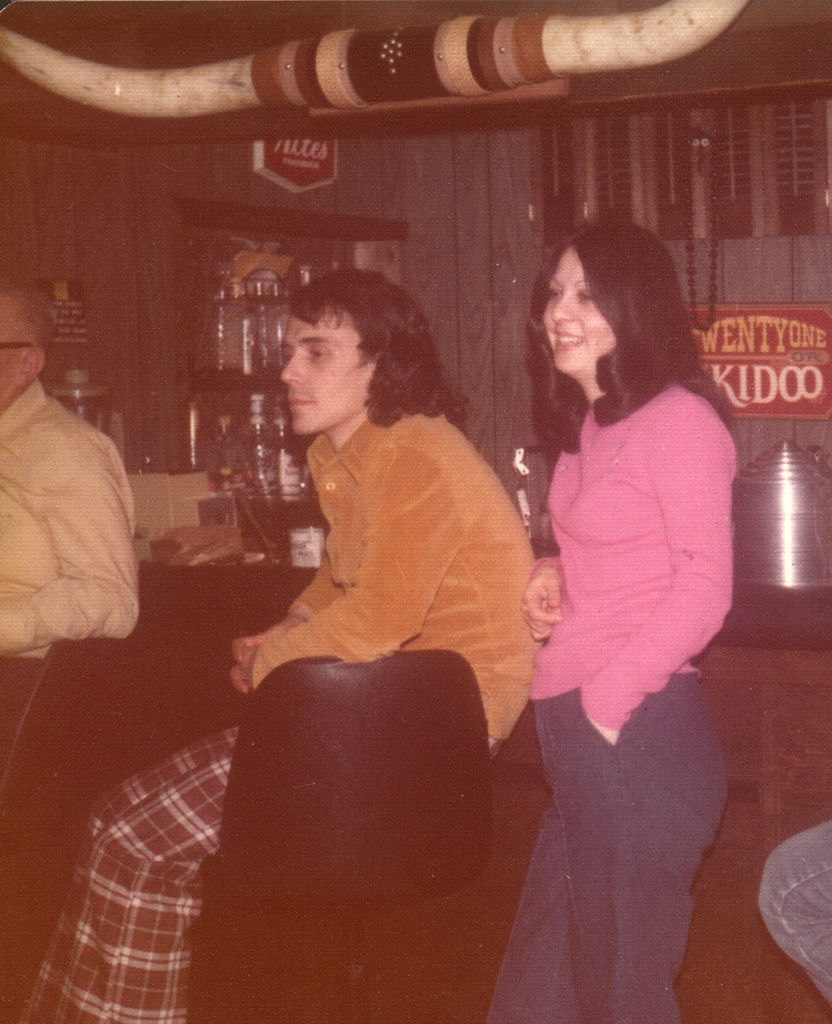

The parties they told me about were fascinating; a who’s-who of the Carter-era Minneapolis art scene, with an odd splash of out of town visitors, bleary-eyed late-night revelers and anyone else who was able to talk their way in. “We never had less than a hundred people up there,” says Eric, “but never more than 150. We had to keep it kind of exclusive; otherwise, it would get out of hand.”

In 1981, the gallery had the distinction of showing what is possibly the very first piece of anti-George W. Bush art in America: a drawing by Michael Brandt, from a larger series of defaced images of the children of Reagan’s cabinet members. This one in particular was a crude mimeograph of then-Vice President Bush’s two sons with silver paint scribbled over their faces, “silver spoons” scrawled presciently across the bottom. At another memorable opening, performance artist Jim Schober assembled, over the course of a night and to the cheering of the crowd, much of an actual John Deere tractor from parts he’d smuggled up piece by piece, using only a high-powered drill and some bolts as his tools. The piece was called Lifter Puller – a title that a young, hard-partying teenage musician named Craig Finn in attendance made note of.

There were other highlights through the early ’80s, but by 1982 the fun was wearing off. “We were kind of tired of having our life’s work be this thing we could never talk about,” says Rachel. “We were proud of what we did up there, but the silence was corrosive.”

Bill Christensen died in 1982 at the age of 79 and, after four years of secret exhibitions, it seemed to be a good time to hang it up. “It was a tough time,” says Eric. “Bill passed, then my mother a short while later; and then both of Rachel’s parents passed away soon after that.” Rachel agrees: “We had no money, no savings. We were definitely having a crisis of spirit. We’d been out of school for almost ten years, and suddenly we seemed very alone.”

One night in 1982, after a miserable month of unexpected deaths, Eric and Rachel were cleaning up from one of the final openings, looking out the window of the IDS from Farm Accident. Both thought they saw a shape in the western sky. “It was the Angel Moroni,” Eric writes simply. “I can’t tell you how I know that – the only contact I’d had with Mormonism was our heroin dealer, who was a lapsed LDS. But I knew it was him.”

They both understood that it was a sign – they were being called out West to become Mormons. “We didn’t even think twice,” says Rachel.

Eric and Rachel may have been great contributors to the Minneapolis scene, but they were never deeply a part of it. When they moved on, they left few friends behind. By then, the Warehouse District scene was coming into its own, and the focus was shifting to commercial spaces in that part of town, where there was no need to sneak around via freight elevators. By that time, Minneapolis was enjoying a cultural resurgence with an artistic elite all of its own, in such figures as Prince, and there seemed little need to import luminaries from the couple’s New York days.

Quietly, in early 1983, Rachel and Eric left Minneapolis for Salt Lake City, where in the fall they enrolled in Brigham Young University’s MFA program. They still live and work in Salt Lake City today – Eric is currently Assistant Curator of Sculpture and New Media at the Salt Lake City Museum of Contemporary Mormon Art, and Rachel earned her PhD and now teaches printmaking and church history and doctrine at BYU. It was in Salt Lake City that I was able to contact them via email, and piece together the stories and quotes you’re reading today.

“It was raucous, it was amazing. The view from the 46th floor when the sun is rising is unlike anything else,” writes Rachel. “It seems like a lifetime ago.”

“It’s all so unlikely,” agrees Eric.

Please contact the author with your memories of Farm Accident here.

Andy Sturdevant is a Minneapolis-based artist, curator, and writer.