Famous for Being Famous: Scott Seekins

After three years in the Twin Cities, Alex Starace finally understands the genius of performance artist Scott Seekins.

It all started innocently enough: I was having an ice cream at Sebastian Joe’s. The shop, like many coffee and ice cream places, hangs a rotating display of local (and oftentimes tacky and semi-professional) artists on its walls. I looked up and this time the art was his – Scott Seekins’s. This was too much: I had a sneaking suspicion that either I was stalking him or he was haunting me. I’d seen him in an elevator several times, in the IDS building, walking down Nicollet Mall, at Pizza Luce, on the bus, and at the CC Club. All my friends have seen him – one has seen him at least fifteen times in the past nine months. Everybody knows who he is. People speculate if he’s wearing a wig or not, why he sports such a ridiculous mustache, whether he wears his outfit around the house, and why, of all things, why, he keeps doing what he’s doing.

And so who is he? He’s a man, in his fifties or so, who wears all-white suits in the summer, and all-black suits in the winter. His outfit is a sort of performance art. He has a pencil-thin mustache, a black headband, and an over-abundant sprouting of black hair that flops back down over his head like a healthy fern. To put it bluntly, he stands out. For over twenty years he’s been a staple on the South Minneapolis scene – a curio, a subject of gossip, a passing bit of color. If nothing else, his persistence is phenomenal, so much so that, after hearing he’s been quoted as saying, “I am art,” I’m convinced that he’s right: he, himself, Scott Seekins the personage, is a piece of art. But how and why? I can only explain by first talking about my experiences with him – his art is of a very interactive nature.

I used to have an internship in the same building in which he has a studio, and so we’d occasionally share an elevator. These are the only instances in which I’ve ever talked with him. His conversation seemed quite regular and, aside from his hair, his outfit didn’t strike me as overly strange – I hadn’t yet realized he was always wearing the same outfit. Later that year, after I’d seen him numerous times and realized his schtick, I saw an advertisement for an exhibition of his. The ad ran in The Rake, and it was a full-body photograph of him. He was simpering into the camera and in big bold letters across the top ran the phrase “COME LOOK AT MY ART – PAINTINGS OF ME,” or some other overly forward invitation. My roommate and I, upon seeing such navel-gazing frippery, busted a gut laughing – he looked so pretentious, so ridiculous, and so pitiful. In the same issue of The Rake was an interview with him. In it, he described his trouble with women – apparently he wears his outfit on dates and so has trouble keeping a girlfriend. And when he does stay with a woman long enough to meet her family, his success is his undoing: every parent he’s been introduced to has strongly disapproved of him. Mostly, again, on account of the outfit.

It wasn’t until recently that I’d had much more contact with him. I saw him in the CC Club (a favorite bar of his) and told my date about his exploits – namely, that he wanders around in the same outfit all the time, as form of performance art. This captured her imagination, and since, she’s been seeing him nearly non-stop – she’s been looking. I myself had begun thinking about and seeing him more than I felt was healthy. His paintings at Sebastian Joe’s were the breaking point: Who is this person, and why do I see him so often? I decided to find out.

He’s an artist who graduated from MCAD in 1964, he’s extremely good (professional quality) at making accessories for model railroads, he likes fly-fishing, from all reports he’s very friendly and approachable, though he was badly assaulted in 2002 in part because of his outfit – he has trouble with people insulting and bullying him. He’s often listed as people’s favorite “familiar stranger,” and he has an obsession with Madonna (the religious figure) and Britney Spears (the pop star). Correspondingly, many of his paintings are either of a Madonna or of himself interacting with women. (In one work, he’s marrying Britney Spears and thinking “How I’ve waited for this moment…”)

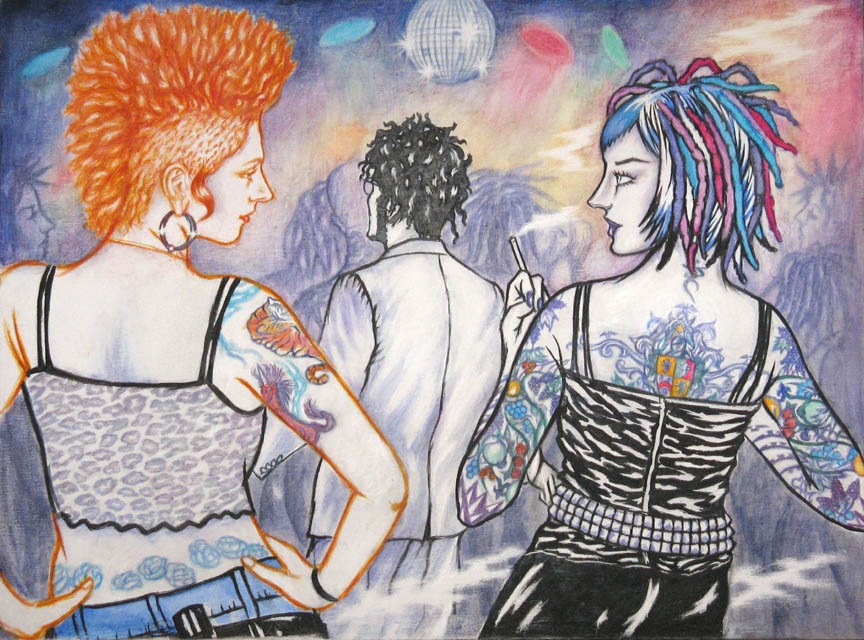

Overall, he’s a person with an active life, and a sense of humor. To take an example of his humor, in one of his paintings, I’ve Seen You Around Forever, Seekins stands in the background at a dance club, beneath a disco ball, his back to the viewer. On either side of him, in the foreground, are female punk rockers, complete with tattoos, dreads, and cigarettes. They gaze upon an isolated and alone Seekins and look bored, uninterested. It’s obvious they’re thinking the title of the piece – the artist’s humorous awareness of his status as a local icon comes through.

In another piece, Is It You, My Prince?, a woman in royal clothing lies on a bed. She’s looking eagerly at a man, Scott Seekins, who’s just burst on the scene in knightly regalia, ready to rescue her. It’s hilarious, particularly because the faces of the characters have Lichtenstein-ish dots – it’s a cartoon. And this is where it all comes together: Seekins’s work is about self-abnegation on a grand scale. Here we have a man baring his mundane fantasies and longings to all of us, making himself an everyman to an entire city.

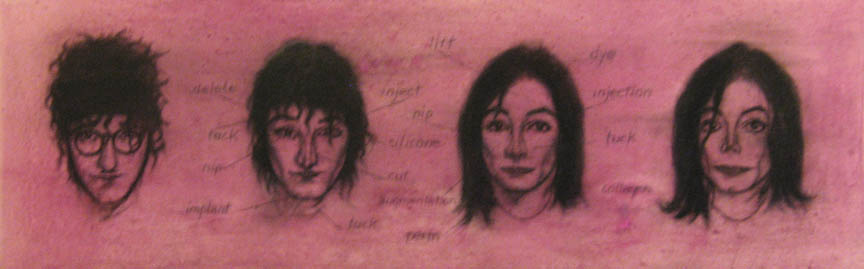

Flash back to pre-fame Seekins. There’s a photograph of him taken in 1974 by Thomas Arndt, and currently held in the MIA collection. In it, we see Seekins as a youngish man, holding a can of beer. There are premonitions of his current hairstyle and outfit, but for the most part he’s nondescript. There’s something haunting about the photo – like looking at old pictures of your parents and realizing that they lived rich and full lives before you were born: here is the man that we know (sort of) and love (sort of) years before, when he wasn’t a full-blown kook, but just a guy. And then compare this to one of his current pieces, Metamorphosis Two, in which, in a very schematic drawing, we see Seekins’s face on the left side of the canvas and Michael Jackson’s on the right. In between are two more faces, mid-transition, accompanied by helpful diagrams that show how to nip, tuck, cut, perm, augment, and implant Seekins’s face in order to change it into Jackson’s. It’s rather creepy, made more so by the fact that Seekins has already done something similar.

And yet his behavior is usual (consider his hobbies: fly fishing, model trains, and going to bars) – what is unusual is that we notice it. In other words, many of us can boast that we frequently go out, but few of us can boast that we stand out while we do it. And therein lies the genius of Seekins’s work: he invites us along to speculate, to take or leave what he does. In an era where self-indulgence is the norm – where artists dump their innermost feelings on the viewer as a matter of course and justify incomprehensibility by “personal meaning,” Seekins does neither of these things; the memoir is currently the ascendant literary form, and yet Seekins tells us almost nothing about his personal life. Instead, he’s managed to tag himself in a very unassuming way: he looks weird, so if you want to keep track of how many times you’ve seen him and deduce from that what his life must be like, you can. But you don’t have to, and he doesn’t push himself upon anyone. He, just like you, is a person living among a crowd of other people, and if you become interested enough – as I ended up being – to think about him and wonder what he does and how he lives – then you end up thinking of his entire life and thinking of it in terms of a piece of art.

His actual paintings reinforce this. Almost all of them are in a particular genre: Metamorphosis Two, architectural blueprint; I’ve Seen You Around Forever, seventies stoner style; Is It You, My Prince?, Renaissance festival / comic book; Time for Hope Has Passed, anime. As a result, Seekins tells us very little about himself, and a lot about Minneapolis and its inhabitants; Seekins’s paintings place himself in the cultural context in which he (and all the rest of us) live – he gives us a mental mapping of the physical space he traverses. He goes to a hip-hop concert at night and the next day he paints himself as a pimp standing next to a pair of hoes. It’s a natural thing, something we all indulge in. And Seekins does it in such an obviously referential and open way that his imaginings are less personal and more universal (or at least more American) than one would think possible. He is, rather prolifically, painting the daydreams and fantasies many of us have, at least passingly, thought about.

And so when he says, “COME LOOK AT MY ART – PAINTINGS OF ME,” it’s not so much that he’s giving us self-indulgent tripe, but that he’s regurgitating the culture and life we all think about and deal with every day. He is Waldo in Minneapolis’s metaphorical game of Where’s Waldo – he’s in the scenes we all walk through. And so when we find him, we find ourselves: a person, living, strange, full of yearnings and ideas, heavily influenced by pop culture, and surprisingly private (he has no website or blog and the jocularity in his paintings hold the viewer at arm’s length). He is, then, no different from the rest of us, except in that he’s devoted a good portion of his life to showing us as much.