Family Reunion: Musicapolis at MCP

Rachel Joyce, redoubtable scenester, goes through the family album of her dreams at the Minnesota Center for Photography's show "Musicapolis: Scene and Seen 1965-2005."

I went to my first reunion last week. I had skipped my five- and ten-year ones. In some ways it was just like I’d been told by friends who’d done a better job at keeping up: waiting around to recognize or be recognized, thinking of a way to sum up my last decade by connecting the dots of only my accomplishments and rites of passage. Excitedly scanning the crowd to see who still looked good, kept their hair, had wedding bands, slimmed down, etc.

What was different was that no one at this reunion was going to be checking for me. And I would only recognize them from photos or if I was at their feet looking upwards. I was at the opening of the exhilarating Musicapolis photography exhibition at the Minnesota Center for Photography (curated by Colleen Sheehy).

I was not a part of this class. I was the freshman at the senior prom that sneaked in to handle punch duty. As a ravenous fan of Minneapolis music since my early teen years in the mid-80s, Musicapolis: Scene and Seen, 1965-2005, was close to my soul. For years before my first fake I.D., photos of the Replacements, Husker Du, Prince, the Time, Otto’s Chemical Lounge, Information Society, Urban Guerillas, the Wallets, and more clipped from the local papers and stuck obsessively to my bedroom walls were my only glimpse of this scene that captivated my imagination. And in true fan form I wish I could take each reader by the hand and lead you through the exhibit and share in liner-note detail my memories of the musicians. Knowing how utterly annoying that would be, I will instead share a few of my favorite images of the exhibition.

Bill Carlson offers the show’s earliest images. His exacting timing captures his subject’s expressions the moment they come to fruition on the face. The result is a collection of candid shots of the Beatles during their 1965 visit to Met Stadium that vividly convey each member’s personality. Even his image of a throng of screaming fans pressed against a wire fence manages to clearly capture wonder pooled in eyes covered by horn-rimmed glasses. Carlson’s photos in Musicapolis were taken when he was 17 and working as a photographer’s assistant. Having seen this collection I am curious to see how his innate sense of the subtleties of human emotion developed as his craft matured.

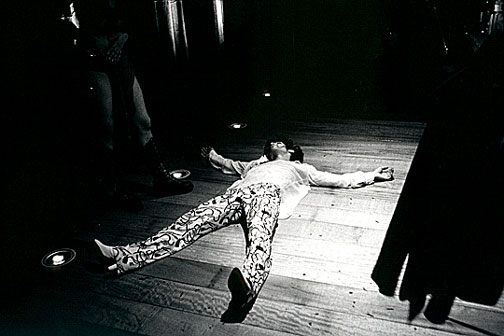

Another stunning example of an artist blessed with an acute sense of when to push the shutter is the collection by Jay Smiley. Here he captures Maurice Jacox, face contorted in musical reverie, decked out in Harlem Globetrotters short shorts performing at Parade Stadium with Willie Murphy and the Bumblebees in 1970. His group of photos from the late 70s through the 90s include an insider’s perspective of performances and offstage encounters with local and touring acts, including memorable shots of Patti Smith at the State Theater, the Blue Up’s Rachel Olson at First Avenue, and a sweat-bathed Ike Riley surrounded by his fans at the Turf Club.

The deliberately blurred images of Michael Markos poignantly capture the energy and drawing-outside-the lines abandon of the music of his subjects, late-70’s underground music icons the Talking Heads, Iggy Pop, and the Ramones, and local pioneers the Suicide Commandos and the Suburbs. Local music fans will appreciate his back-in-the day images of these musicians from the legendary incubators of Minneapolis music, the Longhorn bar and Kelly’s Pub. His collection of photos felt to me like pages from family photo albums and scrapbooks of friends and boyfriends I knew only in my daydreams.

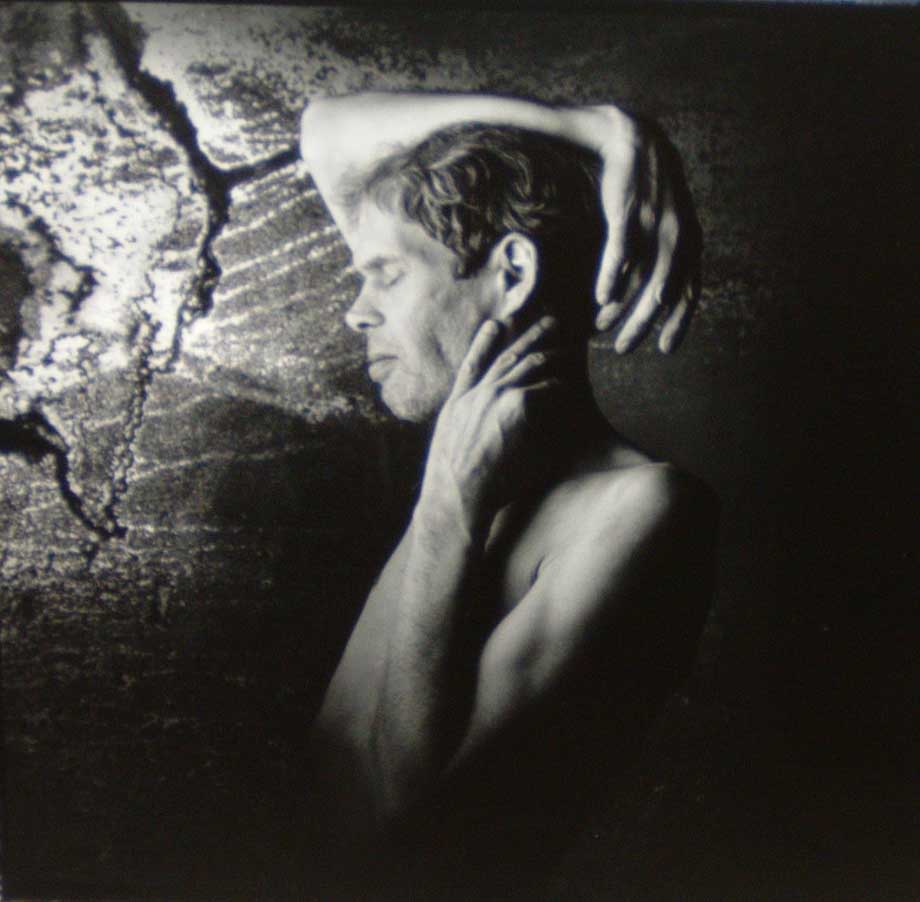

Greg Helgerson’s photos possess such stark clarity they elicited a physical response. If you have ever FELT someone starring at you, or had your breath falter when someone met your gaze, you will understand the sensation of viewing these images. A photo of Alexander O’Neal outside the Guthrie Theater momentarily transfixed me. His lowered eyelids and direct gaze pierced from the photo, making me avert my eyes as if I owed him money. To add to the effect, the photos were intimately displayed sans frames.

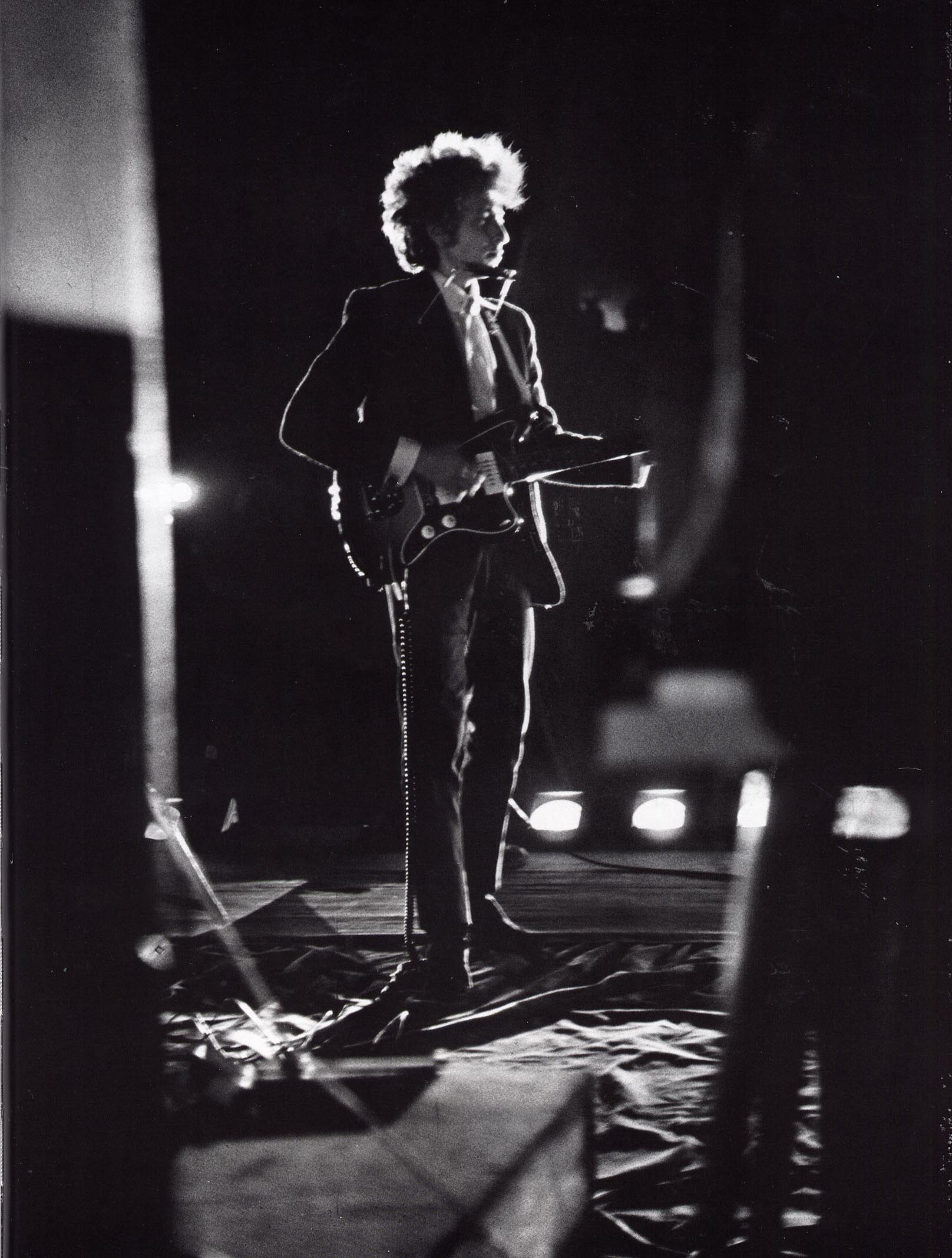

Helgerson’s vast collection, the largest in Musicapolis, includes photos from the 70s and 80s of visiting icons Mick Jagger, Elvis Costello, Madonna, U2, Albert King and particularly striking candid shots of Bob Marley. The collection also contains many rare images of Minneapolis music including Prince onstage at First Avenue, the Capri and the Orpheum in the Controversy album period, and The Replacements and Husker Du in 7th Street Entry.

Photographer Kathy Chapman also has an impressive number of photos of local music from this time. Unfortunately the images are mounted in a jumbled pattern of off-centered frames that makes it very difficult to be drawn to singular photos and challenging to have an intimate connection with individual subjects. She masterfully captures the minutia of her subject’s personalities, including meant-to-be-private glances; her photos deserve the clarity that more standard centered hanging provides.

I was happily surprised with the photos by long-time Star Tribune photographer Jeff Wheeler. Although his Strib work is solid and gives the viewer an accurate representation of the artists stage presence, his photos in Musicapolis capture performers’ unguarded personalities. The images felt like the frame just before or just after the money shot needed to accompany a mainstream news piece. The relaxed approach to these shots revealed a depth of artistry to his work I assume is not always possible given the confines of his assignments.

Favoring a more unconventional approach to shooting her subjects, Kathleen Day-Coen’s work gives the viewer a sense of what it would be like to have been involved in the events she photographs. Her use of saturated color and lighting evokes more subtleties of mood and emotion of the experience of the shots than straight documentary. Her photo of Tim Easton frames him in an exotic, seductive lane of the Bryant Lake Bowl. As much as I enjoy the BLB, I have never seen it as the sublime space Coen gives us here. The accompanying black, white, and spot color photo of Iffy at the Turf Club, obscured by intense washes of red, is mesmerizing.

The photographs of Bonnie Brown display the most astute familiarity with the physical quirks of her subjects than any in the show. The way a lover knows how you brush sleep from your eyes or wrap strands of hair around two, not one, fingers, Brown knows Kat of Babes in Toyland always strains up toward a too-high mic, and she knows when Lori Barbero is ready to flash that smile. I personally thank her for confirming that Curtiss A. keeps up on our neighbors to the north, as a candid shot of him reading a tabloid paper about UFOs documents. This intimacy is heightened by her use of the full spectrum of gradations of gray in her black and whites.

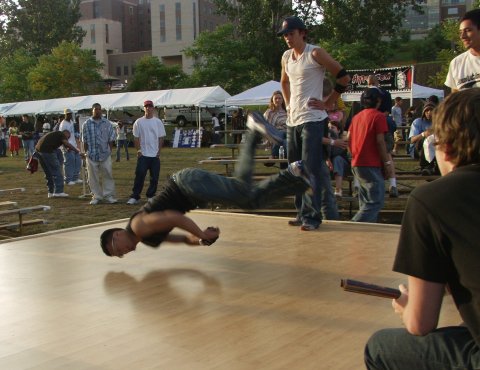

Although the exhibition attempts to display the work of local photographers documenting the music scene of 1965-2005, there were too few photographs from recent years. Of the images from the twenty-first century, the work of Yvette Griffea-Gray was most compelling to me. It is a relief to know that the burgeoning hip-hop scene for which Minneapolis is acquiring a national reputation as a hotbed of talent will be documented with the artistic flair and reverence it deserves. If a similar show is mounted in a decade or two, there will surely be crowds gathered around her images of Pen Soul, DJ Stage One and local breakers just as gallery traffic congested around Terry Gydesen’s backstage access-acquired Prince shots and Mark Norberg’s portrait of Bob Mould.