“Exercises”: Merce Cunningham Draws!

Camille LeFevre has some fascinating conversations about Merce Cunningham in Minnesota, and offers an interesting read on the show of his drawings currently at the Katherine Nash Gallery at the University of Minnesota.

“Exercises,” drawings by Merce Cunningham, is at the Katherine E. Nash Gallery, Regis Center for Art, University of Minnesota, through November 10.

Last week, I talked with my friend, colleague, and Merce Cunningham aficionado Linda Shapiro about the 86-year-old dance icon’s influence on dance making in Minnesota. First, we compiled a rather exhaustive history of Merce here, starting with Cunningham’s long relationship with the Walker Art Center. Since a performance at the Woman’s Club Theater in 1963, the Walker has sponsored almost 15 Cunningham performances since then; a residency in 1969 followed by eight more; three commissions of seminal new works (“Fabrications,” “Field and Figures,” and “Doubletoss”); and the book and exhibition “Art Performs Life: Merce Cunningham/Meredith Monk/Bill T. Jones” in 1998.

Meanwhile, throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company toured the midwest via the Dance Touring Program funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, forging relationships with institutions like the College of St. Benedict which would, decades later, co-commission the 2003 work “Split Sides.” Back in Minneapolis, Shapiro, who studied with Cunningham in the 1960s in New York City, taught his technique at the University of Minnesota. In 1981, she founded with Leigh Dillard the Cunningham-influenced New Dance Ensemble, which continued until 1994.

Carolyn Brown, a founding member of Cunningham’s company and the choreographer’s long-time muse, was the first Sage Cowles Land Grant Chair in the University of Minnesota Dance Program in 1989. That chair, by the way, was endowed by Sage Cowles, the Minneapolis philanthropist who met Cunningham in the 1940s while they were both students at the School of American Ballet in New York City, was a member of the dance company’s Board of Directors for 14 years, and its president from 2000-2004.

So, after all that, surely some residual effects of Cunningham’s radical working methods (both computer-generated and/or chance-based), continually innovative movement and virtuosic technique, or egalitarian relationship between choreography, music, lights, décor and costumes would have trickled down into this dance community. Shapiro thought for a moment and sighed.

“Nope. Cunningham has never had a big influence on the dance scene here,” she said. The roots of German expressionism in Minnesota—via Wigman, Holm, and Hauser—and of classical ballet and Graham technique via Houlton, are just too deep. Even young choreographers coming out of the university today, she continued with a rueful laugh, “just can’t get away from their music.”

“The bigger influence has been on other artists in the community—visual artists, filmmakers,” she added. They have always been intrigued—even incredulous—at Cunningham’s chance working methods, and found a way into his choreography via his collaborations with such eminent artists as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Rei Kawakubo, Morris Graves, Isamu Noguchi and Terry Winters.

One of those Minnesota artists captivated by Cunningham was Tom Rose, who curated the exhibition of Cunningham animal and flower drawings, “Exercises,” at the Katherine E. Nash Gallery. Rose has long followed Cunningham’s dance works; rigorous, open-ended forays into the order, beauty and happy coincidences revealed within chance. Cool and intelligent, Cunningham’s works require a level of technical expertise and aesthetic embodiment his well-rehearsed, sleek, articulate dancers provide.

So when Rose, a professor in the art department at the university, first saw Cunningham’s drawings, he was surprised. “There’s a childlike honesty about them,” Rose said, “a sense of curiosity and wonderment.” In fact, many of these works are so unsophisticated, they look like illustrations drawn by a child for a children’s book. “That’s one of the things that struck me about the drawings,” Rose explained. “There’s a naïvete about them.”

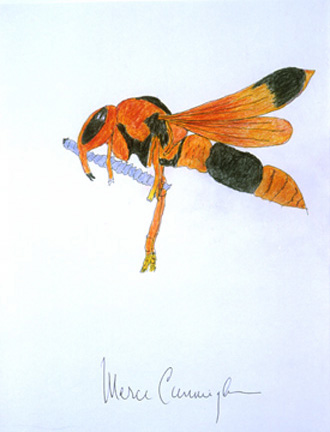

Most of the works—made using colored pens, pencils and crayons—are of animals, insects and birds Cunningham has observed during his travels. Some are rather ghoulish, others project a knowing slyness, one or two are more amorphous blob than recognizable fauna, and a one-dimensional childlike understanding of perspective renders others downright silly. Still, “Untitled (mountain goat)” and “Untitled (wasp)” have a vibrancy and detail that’s arresting.

Still, if these drawings weren’t by a world-famous choreographer whose name encapsulates the clarity of vision, sense of adventure, and integrity of execution we associate with modern art, would they be displayed? Probably not. While visiting with Cunningham last week over the phone, I mentioned the exhibition and asked whether the drawings spring from the same creative impulse as his choreography. He simply laughed and said, “I just enjoy drawing. I don’t do it with any sense of it being art. I’m very pleased that people want to see the drawings. But I don’t push that.”

But it was precisely the juxtaposition of Cunningham’s choreography and these drawings that intrigued Rose. The drawings, Rose explained, “reveal a part of Cunningham that people don’t normally see or aren’t familiar with. I’ve always liked Merce’s choreography, the austerity of it. The drawings are terrifically flamboyant relative to the rest of his work. They’re funny and charming; the antithesis of what you think of when you recall Merce and John [Cage, the composer who was Cunningham’s long-time partner and collaborator] and their work together.”

Cage and Cunningham, for instance, were infamous for their high-art, avant-garde experiments, which included using silence as sound, placing music and movement (created independently) side by side in time and space, and tossing a coin or rolling dice to determine the placement of people or phrases of choreography. But the two artists were also keenly aware of how everyday movement and sounds could be incorporated into their work; and how “chance operations” (as Cunningham still calls them) could not only free the imagination, but reveal serendipitous connections between the components of a work.

“I like the idea of celebration and revelation of the ordinary in Cunningham’s dance works,” Rose said, “and his sense of awareness of the everyday evident through common actions like walking, standing and sitting that appear in his work. As a non-dancer, a non-choreographer, I see in the dance works a quality of moving simply and easily that opens up a space in the mind to ambiguity and change.”

Similarly, the drawings “are very unpretentious. There’s casualness about them, a simplicity that’s found in nature. And they’re plunked down on the page, no decoration or flourishes.” The exhibition also includes Cunningham’s pen-on-paper notations for dance pieces like “Inlets” and “Roaratorio”—in which lines connected to dancers’ initials often conclude in spaghetti-like tangle.

“Cunningham, whether he’s drawing or choreographing, observes the ways things are,” Rose said. “A lot of what he’s interested in is the process.”