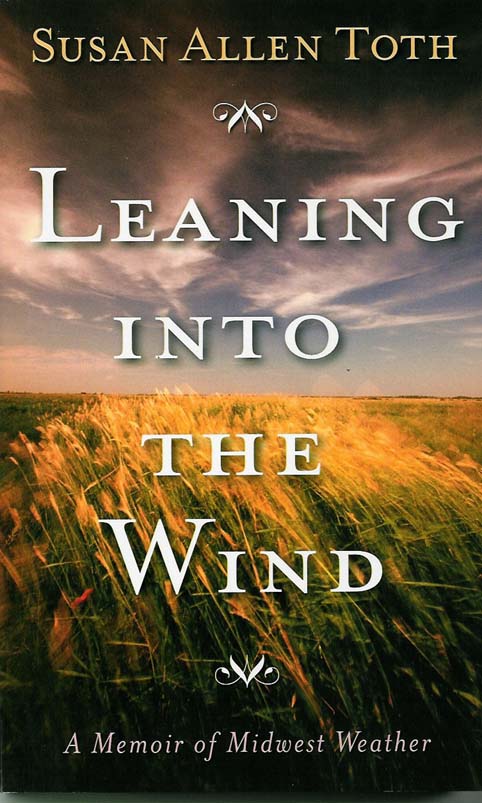

Essays in Search of a Reason to Live: Leaning Into the Wind

Ellen Sandbeck finds certain kinds of thoughts on the weather to be as tedious as conversations about the same subject.

Susan Allen Toth, a mediocre writer in dire need of a thesaurus, has

written an astonishingly trite book about how her boring life was

affected by completely normal experiences with weather. The most

interesting thing about the book is that the University of Minnesota

Press published it; they must be really desperate.

The first chapter is “interesting” only in the Minnesota sense, inducing

as it does a kind of verbal vertigo as it jumps to a different time and

location with each new paragraph. The second chapter, which contains

the phrase “growing up in the Midwest” more times than I cared to

count, is a stupefying recital of the obvious: people in the upper

Midwest wear so many clothes in the winter that they are rendered

unrecognizable; almost the entire population of Minnesota goes outside

to enjoy the first nice weather of the year; midwestern weather is

changeable.

This book may be of some slight interest to denizens of a far-off

galaxy who want to read up on what they should wear when they invade

the planet Earth. I can’t imagine it being of any interest whatsoever

to any Earthling.

(I read the rest of the book while jumping on the mini-trampoline. Bouncing is a prophylactic against coma.)

I will be skipping over essay numbers three, four, and five entirely, since they are so bland that I cannot even mock them.

Essay number six is about looking out at the weather through a window. It is chock-a-block with scintillating observations such as this one, which was brought on by the sight of a gently blowing windsock in her backyard: “We too had wind.” I was grateful that she allowed her readers a half-paragraph of rest before hitting us with the following: “Like most urbanites, I have seen much of my weather from behind a window. Midwesterners are deeply attached to their windows.” (The book wouldn’t stay open while I copied that section. I was forced to break its spine.)

Sometimes Toth really breaks loose and observes the weather from behind the windshield of a car when she and her husband “…take the long way home and turn off the freeway onto country roads. Oh, how we widen our eyes as the landscape unrolls before us.”

My copy of Toth’s book was soon studded with colored paperclips marking passages in which she admitted not only that she knew nothing about a particular subject, but that she was unlikely to attempt to enlighten herself. Essay number seven earned several paperclips, one marking this passage: “From time to time, after I had studied just enough minimal science to fulfill my high school and college requirements, I would temporarily grasp the basic principles of air pressure. Then I would promptly forget them.” This is rather astonishing since she claims that weather watching is one of her main preoccupations.

Toth is quite interested by blizzards, and the subject seems to have inspired her to do some actual hands-on research: “Midwesterners who can stay quietly at home, electricity and heat intact, may be pleased and excited by the word, ‘blizzard.’ (Dairy Queen has invented a gooey ice-milk treat, packed with chunky sweets, called a Blizzard.)” The parenthetical comment is Toth’s.

I doubt that this book required the services of a fact checker.

Essay number eight is a long whine about the existence of insects in the summer. Toth writes: “Everything bites me, everywhere.” “I suppose I should buy an illustrated book of bugs so I could look them up…But I don’t want to know them any better.”

But astonishingly, it later appears that Toth can actually tell the difference between a mosquito and a barn swallow, and informs us that she has, on occasion, had a mosquito enter her house and bother her at night. I cannot help wondering whether her response to this unusual situation (she smears her arms, hands, neck and face with DEET) bothers her husband.

Toth’s last essay begins: “I cannot imagine living in the midst of Midwest weather without sometimes thinking about God…”

By this point in the book, I would have been quite astonished if Toth had admitted to being able to imagine anything at all, but I found it rather touching that she believes so strongly in God that she can make the following impressive and probably ill-advised leap: “My mother nurtured tender petunias and tomato plants, and hail had ruined them more than once. So when the implacable Lord smote Pharoah, I knew how bad it was…”

And it was bad. The End.