ESSAY/FEATURED FORUM: What’s With the Kids These Days?

Michael Fallon reflects on "Young Artists and How the World They're Creating Will Be Completely Fucked Up, and Perhaps That's As It Should Be." We want to know what you think--read the essay, then weigh in on the mnartists.org forums.

TWO WEEKS BEFORE THE GREAT AMERICAN ARTIST Robert Rauschenberg passed away at age 82 this past May, a group of seven young people, all of them one-quarter of the artists age, stood in front of an audience of about 100 at the 2008 Mpls-St. Paul International Film Festival (M-SPIFF). The occasion was the screening of a film, Disconnected, that the group had made for a class on documentary film at Carleton College in nearby Northfield. As I listened to these kids answer questions from the audience about their film, several subtexts to the event came to mind.

First, it was odd that these students from blink-and-miss-it Carleton were, for the most part, calmer and more relaxedsmug almostthan any twenty-year-old has a right to be in front of such a large audience. This is especially true considering the event, a notable international film festival, was olderat 26 yearsthan these kids were. But then, this may not be so unusual after all, given the numerous reports from those in-the-know which suggest that most kids of this agethose of the so-called Generation Y, born after about 1980have come to believe that attention and fame is their very due. According to a 2006 survey by the Pew Research Center, 51% of 18- to 25-year-olds identified to be famous as one of their top two goals. This was above to help people who need help (30%), to be leaders in their community (22%), and to become more spiritual (10%), but behind the number one choice (to get rich, 81%).

_________________________________________________

According to a 2006 survey by the Pew Research Center, 51% of 18- to 25-year-olds identified to be famous as one of their top two goals. This was above to help people who need help (30%), to be leaders in their community (22%), and to become more spiritual (10%), but behind the number one choice (to get rich, 81%).

_________________________________________________

Second, as I listened to these young filmmakers talk, a strange thought struck me: at the same time that the aspirers seemed confident their career was (finally, gosh!) well underwayrushing outside afterward like movie stars on the red carpet to take a group marketing photoit was near miraculous that the venue for their film (i.e., M-SPIFF) still existed. While the festival was healthy enough this year, with more than 140 films from 40 different countries, last years event showed far fewer films to scant fanfare, and buzz had it that the organization overseeing the festival, Minnesota Film Arts, was selling off assets to deal with a ballooning deficit. “We didn’t know if we were going to have enough money to pay bills to have a festival,” said Al Milgrom, who, despite being older than Rauschenbergs age at death, was widely credited for rescuing M-SPIFF this year, after taking a few years off due to health problems. Whats truly ironic about this? A cause for the festivals recent struggles may be that young audiencesmuch like these fame-seeking film studentswho once kept alternative film festivals and other such events afloat are no longer showing up to support the cause. It is remarkable and fortunate that Milgrom, who, in 1962, founded the org that would eventually start up M-SPIFF, still showed up to rally people to the cause after all these years. Because the truth is such arts events (which, after all, play a crucial role in helping young artists become known) are rapidly dying off, no thanks to the young generation that seems unwilling to attend them.

Finally, it was clear to me that the abundant self-confidence on display by these kids wasn’t necessarily evidence of skill or achievement. The film they made was actually not all that good; it was not revealing, not at all introspective, and it made little logical sense. The subject of the filmto follow three of their fellows who pledged to give up their sundry electronic devices (i.e., to become disconnected)for the final three weeks of the semester, was simply contrived to fulfill their course requirements. And though there were a few funny moments (such as when two students tried to figure out how the librarys three old typewriters worked), in the end, the films characters went through little growth, and Disconnected didn’t have much traditional narrative arc. The rather shallow and blasé conclusion of the film seemed merely to be: Wow, its amazing how much valuable time we young people waste on our computers, though I sure wouldnt give mine up again!

ONE CANT REALLY FAULT YOUNG PEOPLE their personal blind spots regarding their own originality (or lack thereof). Every young generation sets out to reinvent culturefirst by pooh-poohing the idea that any original thought has been had in the centuries leading up to their arrival, then by tossing up their supposedly (but rarely actually) new takes. How could these disconnected kids intuit, for instance, that the majority of the population (anyone older than, oh, about twenty years old) still remembers an unwired world, and so would find their fabricated struggles and shallow conclusions fairly ridiculous? Still, common as the myopic creative ambition of young artists is, this blindness can benow, in an age of near-ubiquitous youthful delusions about fame and fortuneespecially problematic.

_________________________________________________

Youthful hubris is (and always has been?) affront to older, established artists and grunt-workers who’ve been doing hard time for years to keep culture alive. In the end, such arrogance is taken as an acte provocateura nasty Molotov probably destined to blow up in the throwers own naïve face.

_________________________________________________

This youthful hubris is (and always has been?) an affront to older, established artists and grunt-workers who’ve been doing hard time for years to keep culture alive. And such arrogance is often taken as a negative acte provocateur that, in the end, causes the most harmat least in terms of turning off future audiences and potential alliesto the wanna-be revolutionary him/herself. Its a nasty Molotov destined only to blow up in the throwers own naïve face.

Now, Im entirely aware that these musings on my part may just be the usual generation-based sour grapes (more on this below) coming from someone who feels the creative imperative slipping from his hands. In fact, my wariness of being charged a grumpy has-been has kept me from writing on this topic until now, although I have been pondering the subject for more than two years. After all, every aging generation produces essays just like the one Im writing here. The argument, in effect, goes like this: the nascent generation is misguided, culturally and in most every other way, and once we elders grudgingly hand the world over to them, everything we’ve worked for will go to pot.

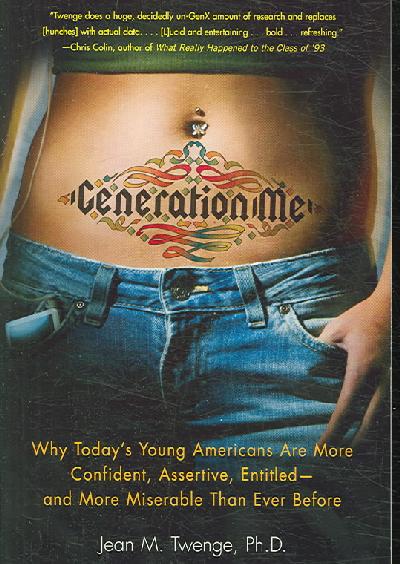

My particular concerns about kids today go back to an intense experience I had in early 2006 leading a group of ten people between the ages of 21 and 28 on a large research project. It was then that I first became aware of the fairly sizeable chasm between my generation and theirs. In the wake of my own frustrating interactions, I’ve remained sufficiently concerned about what sort of future these artists were setting themselves up for to keep seeking info about this emerging generation. And it turns out I havent been the only one. In the past two years, the generation most commonly known as Y born between 1980 and 1997 (give or take a few years, depending on whom you talk to)has become the focus of much observation, study, and commentary in scores of articles, both popular and academic, and books, including: The Dumbest Generation by Mark Bauerlein, Millennials Rising by Neil Howe, Managing Generation Y by Carolyn Martin, and so on. Much of this attention may have to do with this groups connection to the Internet and wireless revolutionsas so-called digital natives, who cant clearly recall a time prior to these tech developmentsand with the rapid social and economic changes which have accompanied them. One of the best documented of these books, Generation Me by psychologist Jean Twenge (who counts herself a member of the generation she has studied), is also one of the most damning assessments of Gen Y.

Young people today, writes Twenge, have been consistently taught to put their own needs first and to focus on feeling good about themselves. She further claims that, despite what you might expect, such self-pampering has done the group nothing but harm. Twenge cites numerous studies which offer evidence for a host of problems among her generational cohorts: a decline in manners and regard for social rules; a disengagement with civic concerns; a tendency toward cheating and an antipathy toward authority; a strong sense of entitlement and inability to take criticism; high levels of drug use; loss of faith in the rewards of responsibility and hard work; increasing sense of loneliness and an inclination toward shorter relationships and sexual promiscuity; rising levels of depression, anxiety, panic, and nervous breakdown; and suicide rates twice what they were in 1950.

Despite its myriad problems, this young generation also hastellingly, and incongruouslya remarkably high sense of self-regard, or what Twenge calls a cotton candy sense of self with no basis. In psychological terms, according to Twenge, her generation is afflicted by abnormally high rates of clinical narcissism, a pathology with numerous manifestations (many of which are listed above). In fact, her discovery of increasing rates of narcissistic personality disorder among recent annual surveys of college freshmen is what initially alerted Twenge to her generations problems. Much of the blame for this, according to her research, falls squarely on educational and parenting philosophies that came into vogue after 1980, which focused on developing self-esteem in children. She explains, over the past decades Gen Y-ers have been told, over and over in school and in the home, that it is who they are, not what they do, that is important; that they are valuable and worthy, no matter their accomplishments; they are simply special. Ironically (or perhaps not so ironically), such ego-boosting has resulted not in more well-adjusted kids, nor in more accomplished ones, but in a whole host of disconnects: unrealistic expectations for success; a lack of interest in striving for accomplishment; an inflated sense of the value of their own efforts; taking for granted the nullity of others’ opinions; an overall thin-skinned-ness; a diminished capacity for extended study and deep thought; and frustration and disappointment when realizing that others dont share their high self-regard.

The nicknames that others have given to Gen Y tell the story: The Look-at-Me Generation, Generation Me, the Dumbest Generation, the Entitlement Generation, Generation Why? Instead of creating well-adjusted, happy children, Twenge writes, the self-esteem movement has created an army of narcissists Praise based on nothing teaches only an inflated ego. The purpose of school is for children to learn, not for them to feel good about themselves all the time. Twenge ends her book, in fact, with a near-desperate plea for immediate reform of the education system, gearing it more toward the teaching of skills and accomplishments over self-esteemlest we face a long future of underachieving, unfocused, unproductive, and disgruntled kids .continue reading this essay in the mnartists.org forums

About the author: Michael Fallon is an arts writer, nonprofit administrator, and educator based in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Since 1998, he has written more than 160 reviews, feature articles, essays, and profiles for publications like City Pages, Art Papers, The Orange County Weekly, Saint Paul Pioneer Press, The Pittsburgh City Paper, Fiberarts, Public Art Review, Art in America, and mnartists.org. Michael has been a member of the American chapter of the International Art Critics Association since 2000, and in 2002 he founded a local arts writers association, the Visual Art Critics Union of Minnesota (VACUM).

>>FEATURED FORUM: Read Michael Fallon’s provocative essay, in full, on the trouble with Gen Y artists, then enter the fray, yourself, by offering some of your own observations and comments during this month-long featured forum conversation.<<