Three Cheers for Age Diversity and Deep Hanging Out

An engagement with the Walker Art Center Teen Arts Council sparks intergenerational exchange, championing as method, and a dazzling snack buffet

“The white wall…it was…nothing…and EVERYTHING!” is but one of the conversation pieces visitors are gifted when they enter the Walker from the parking structure. Subtle in placement is a wall placard with a QR code. The placard states:

When you enter the museum, this is one of the first places you might see. Is every object in the Walker art? The walls? The doors? The chairs? How do you know which features are art? Is this wall one of the most viewed and ignored artworks in the museum? Your art journey begins now!

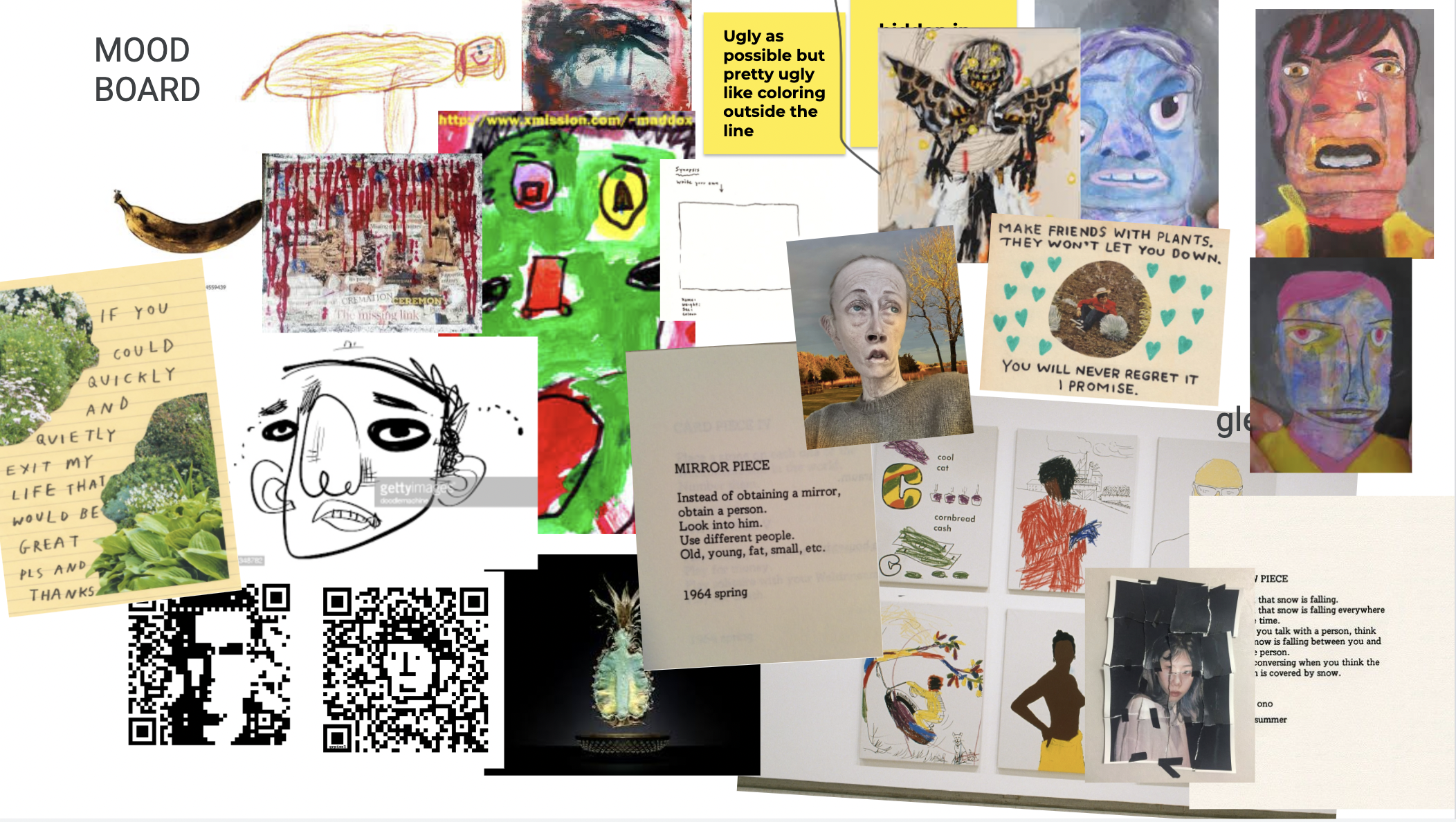

And so it does. There are five more meta-works by the 2020-2021 WACTAC cohort strategically scattered around the museum. Each confronts the viewer with an ontological question. QR codes activate WATAC’s thoughtful, unexpected, and joyfully creative reframings of the focal object or space.

WACTAC—the Walker Art Center Teen Arts Council, a program offering space to teen voices and experiences at the Walker—is the oldest of its kind in the United States. I began with WACTAC in January 2020 as the Artist in Residence for Public Engagement, Learning, and Impact, with a plan to travel from New York to Minneapolis and meet with the teens in person once a month through June and mentor them through phases of project identification, research, and development. I worked with the 2019-2020 cohort first in person, and then on Zoom during those first harried months of the lockdown. I continued on to work with the 2020-2021 cohort.

Without any in-person contact, I was unsure how I might fit into the new cohort. And yet, we were peers from the first Zoom meeting. The intense love of art, self-possession, and astute observations about Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A voided any other definition of our relationship. In meeting a group of strangers for the first time—for a workshop, a lecture, a semester of classes—there is usually a clearer gap between us: of age, experience, culture, context. And it is the work of questions and answers, and traveling through ideas together, that bridges that space. Instead, their intense love and enthusiasm for art sparked my own love and enthusiasm, which is all too often suppressed by the critical distance of evaluating art as an artist, and the stupid been-there-done-that of adulthood.

How do we know a piece of art when we encounter it? What is art? Who is an artist? These fundamental questions that I witnessed this cohort asking every week triggered memories of past encounters with art, and experimentation with ways of being in museums, looking at art, and knowing art. One memory in particular came surging back: the day I almost got thrown out of Dia Beacon for crawling across the floor underneath the Fred Sandbacks as if they were a laser maze, and laying next to the Smithsons as if I were the land of the non-site itself.

Photo courtesy Nancy Nowacek.

Part of an ongoing series, “Doing Things,” this is an example of how I take the world in through my body. In this case, it is an Alexander Calder, Untitled, 1961, in the SF MoMA sculpture garden, 2011. Photo: Bob Holling.

…Sometimes the Clouds Come Back this Way… (2019) is a permanent sculpture by Nowacek at Franconia Sculpture Park offering a place for the public to engage in any sort of use they might imagine from walking a dog to walking mediation or political protest. Photo: Nancy Nowacek.

Photo courtesy Nancy Nowacek.

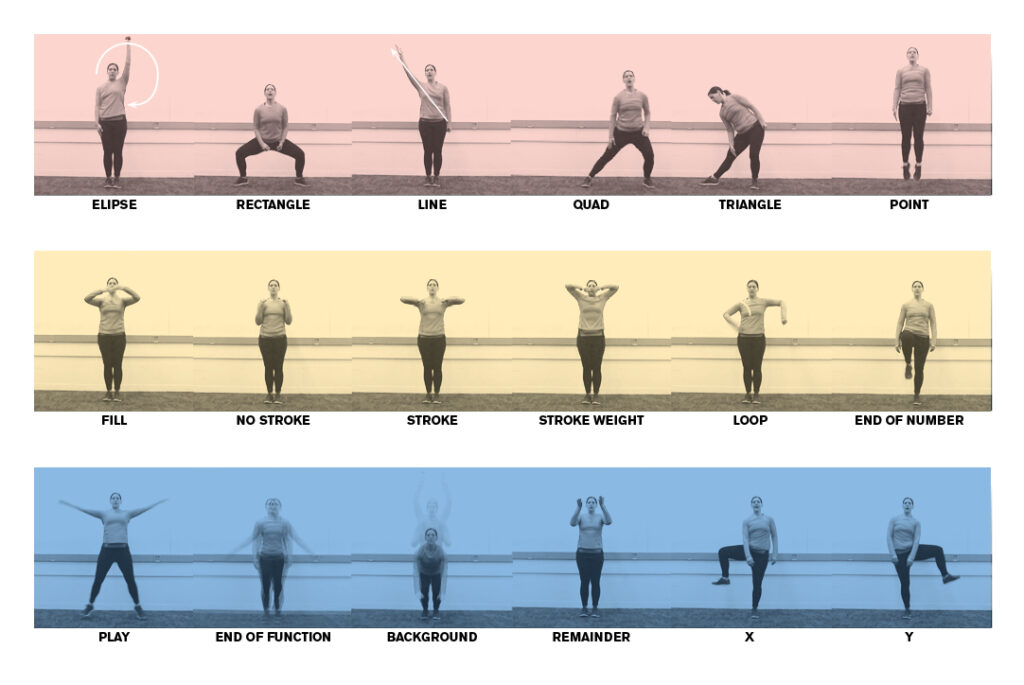

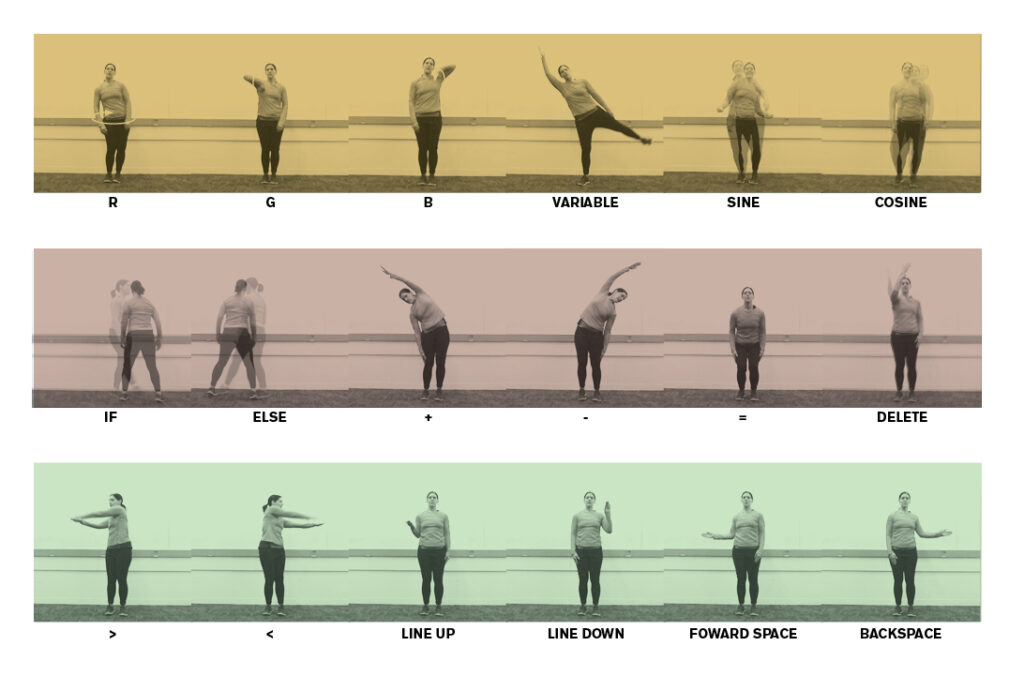

This is one of the forms of creative research in my practice: meeting the world through my body. I arrange my body in space in strange ways, move in strange ways, and build special tools in order understand and feel the world in new ways. It sometimes looks like dance, sometimes like exercise. Sometimes it looks like a task or manual labor. My practice emerged—in part—as a response to digital devices and the ways they essentialize their human operators to eyes, ears, and brains—there’s so much knowing lost in contemporary life.

And in many ways, my practice is aimed to awaken this impulse—to take in and know the world through the body—in others. Because I teach undergraduate students in a Visual Art & Technology program, this impulse becomes helping my students reframe the creative urges that they have as creative research. After all, what is art-making (and all creative practice) if not looking at and knowing the world in new ways? This is a question that my partner and I have been asking through a series of workshops over the past three years with students in New York City, Copenhagen, and Milan, in order to hone a methodology that helps creative practitioners move through their practices as research.

The outline of our process was packed in my bag for my first WACTAC meeting, with the 2019-2020 cohort, in January 2019, ready to deploy. It never made it out. I forgot—in my ardor to do this kind of work with the teens—that they were teens, who had been already at school all day, had come on public transit to the meeting, and it was time to snack and chill. For the record, snacking and chilling as a methodology is underrated. It’s the ease-in, warm-up, social space where inner states migrate outward. It’s the space for setting down the burdens from the day, music or meme obsessions, weird dreams, funny stories. Crinkling of bags and shuffling of chairs formed the background for personalities unfolding: shy, observant, bold, reserved, expectant. In those moments, we become ourselves and a group banded together. Our work those winter months was to move through phases of creative research to uncover and hone a project idea. The outline traveled back for my second visit, early February 2020…and once again stayed in the bag. As we snacked, it was apparent new tactics would be needed: the group was tired and unusually quiet. Maybe it February, or the encroaching pandemic.

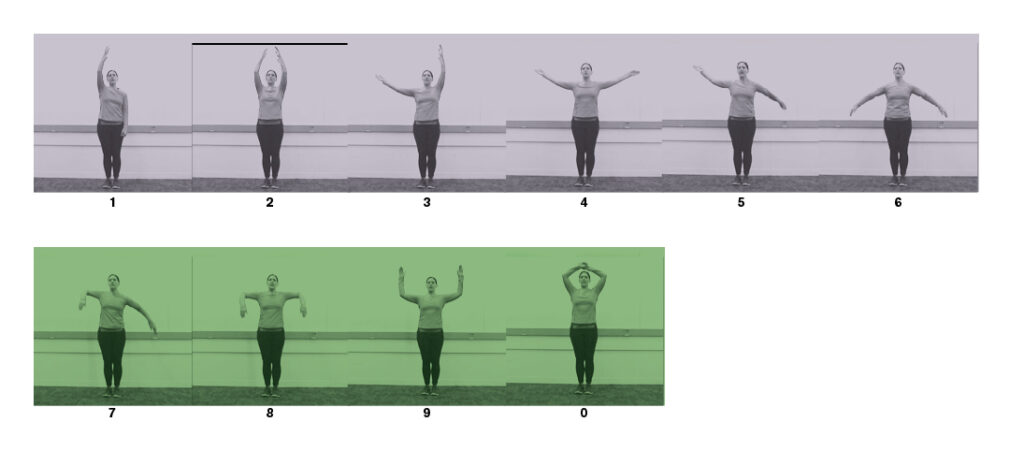

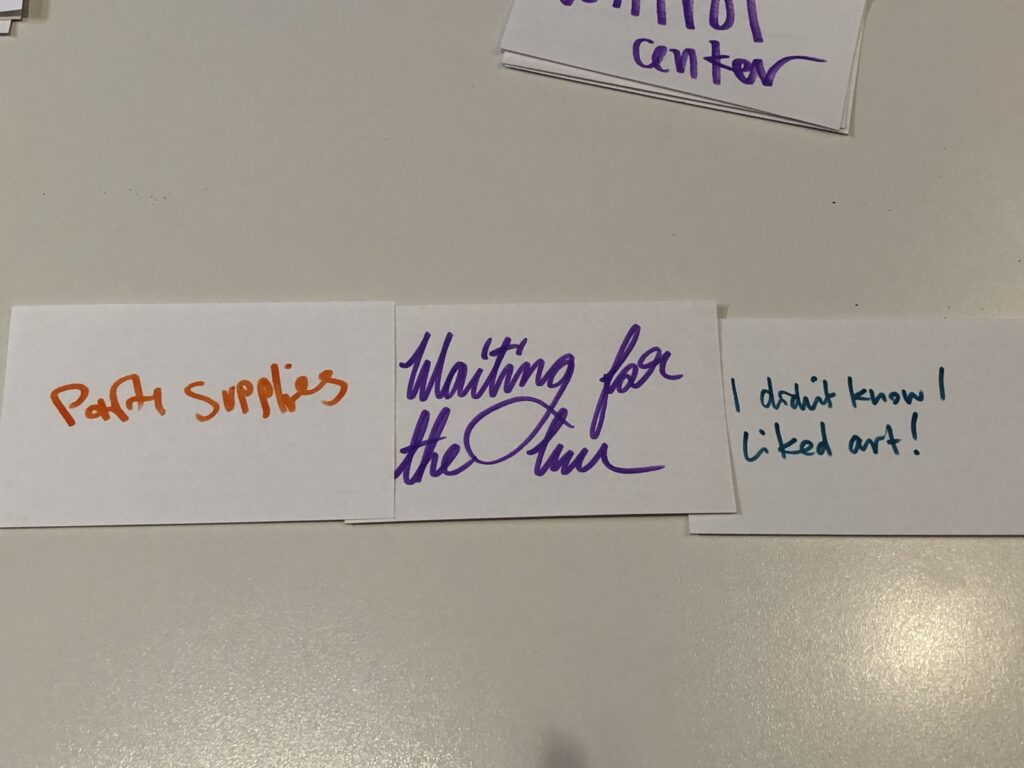

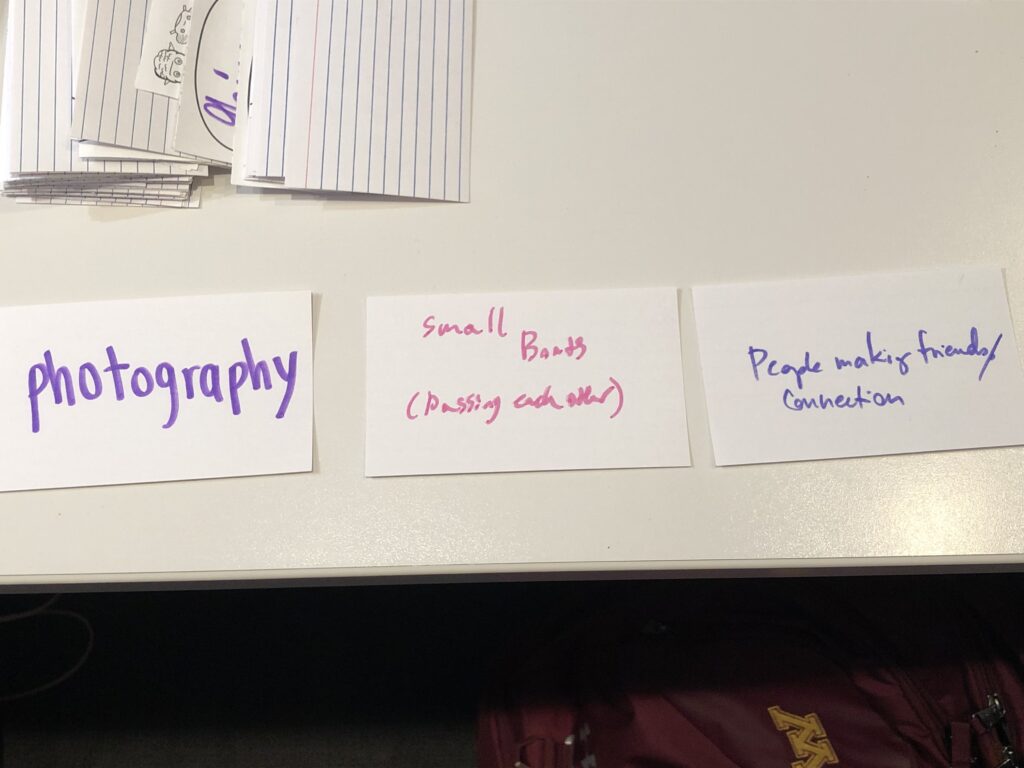

Mentoring is caring improvisation. In these first two visits, I found myself moving between observer, comic, and inventor—creating methods in the moment to help the group shape their ideas into a form. In that February afternoon, the Idea Machine emerged. In listening to the teens’ conversation about their work to date, I devised a process of helping them turn an inventory of resources, social interactions, and audience responses into decks of cards. Choosing a card from each deck dealt a project prompt like “singing / jury duty / people laughing” and “party supplies / small boats / ‘I didn’t know I liked art!’” We were moving in an interesting direction until, well, you know.

As for everyone and everything, the Pandemic Changed Everything, and, most painfully, our ability to gather together in the Walker, which was the special sauce for us all. Even still, I have two insights from my time with WACTAC, twice in person, and many, many times more over Zoom.

The first is this: if not improvising, most often, I was cheering the teens on. Cheerleaders get a bad rap, but our world today of fear-mongering, powered by binary rhetorics of winning and losing, and the tribalism of “us” and “them” is woefully lacking voices of support and encouragement. Neoliberalism has forced focus on our own hustle and turned all others into competitors. We’re so exhausted from fighting for our own survival that we’ve forgotten how to cheer each other on. I often wonder how the world might look if there was as much—if not more—championing and cheering as there is competition. And I think it’s a role into which many more folks with privilege, platform, or power might want to consider moving: supporting the visions of those who don’t have privilege, a platform, or access to power.

As a group of young people from all over the Twin Cities, with all sorts of different backgrounds, cultures, and identities, the WACTAC teens model the world I want to live in. And they are smart as hell. I didn’t always understand their slang, and their interests and choices didn’t always make sense to me. But the invitation given to me was essentially an opportunity to show up and say, “yes, and.”

The power of “yes, and” is in its ability to bridge differences of all sorts: ideas, interpretations, experiences, backgrounds. Watching WACTAC at work, and adding to their creative instincts with even more possibility, expanded our shared imagination. And our respect for the humble potato.1 It was so powerful, I neglected to notice until the very end of two cycles, that we—me, the teens, and the facilitators—had been engaged in intergenerational, or mixed-age, exchange. These kinds of programs are rarely framed as such, and that’s probably because intergenerational exchange isn’t yet in the forefront of our cultural awareness. We don’t think about age diversity as a kind of diversity because, as the last form of “acceptable” bias, age isn’t yet considered a category of “otherness.”

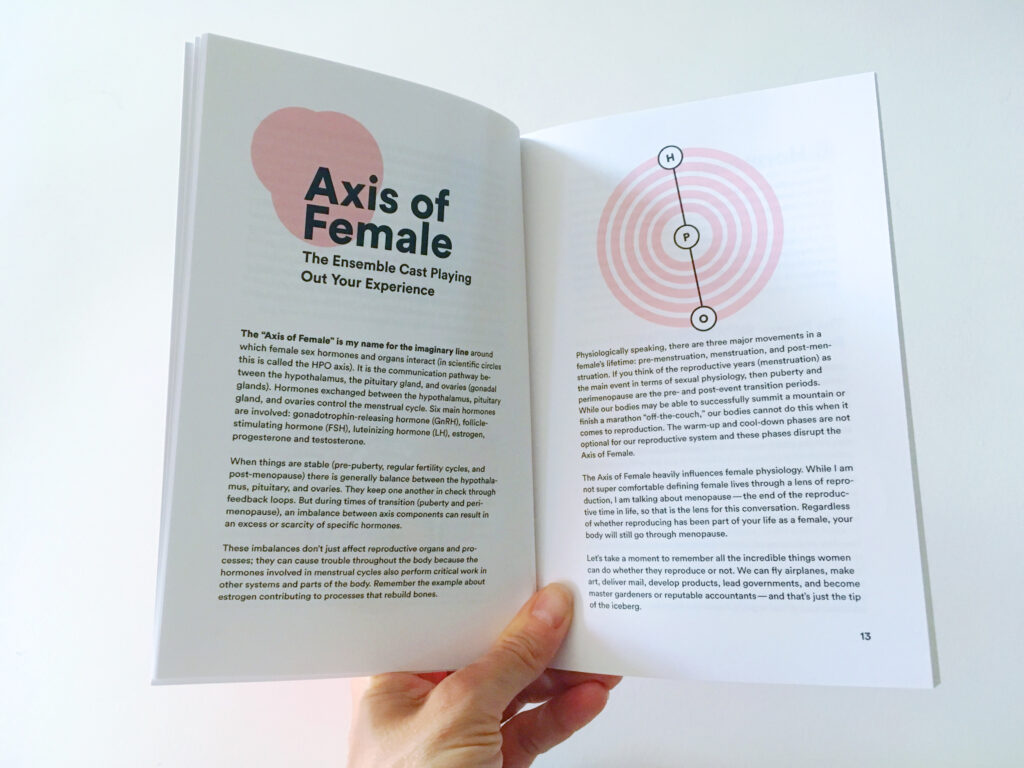

Ageism entered my practice through menopause. About five years ago, Sasha Davies and I, good friends stationed on opposite coasts, were noticing to one another that we were starting to hear stories of early menopause and surgical menopause from friends, all of whom were stunned, shamed, confused, and isolated to find themselves in a biological state that half the world will experience, yet no one talks about. We were even more shocked when we realized that we knew only as much as the ageist and misogynistic crumbs supplied by television and movies had given us. Together we created Menopause: An Imperfect Guide, an introductory guidebook to aging female reproductive health—the first project. M__________, the Menopause Project was the second. It was a pop-up gift shop stocked with artist multiples inspired by menopause, its symptoms, and/or cultural attitudes. Mirrors and t-shirts invited shoppers to “Let Go of The Fantasy” (Amy Khoshbin.) Prints, mugs, and t-shirts claimed, “Growing Older is A Lucky Thing,” and “Celebrate Crones” (Macon Reed.) Folding fans slyly offered “For when the body sneaks up” (Chloë Bass). There were also enameled ribbon-shaped pins for “SWEAT,” and colorful macaroni-styled jump ropes for maintaining bone density and heart health. The shop was a lure for a program space exploding behind it. Free public programs included: The History of Menopause (yes, it has a history); Hormones, Hormones, Hormones; Herbal Approaches to Symptoms, EVERYTHING YOU WANTED TO ASK ABOUT MENOPAUSE AND SEX BUT WERE AFRAID TO ASK, and the Whys and Hows of Powerlifting for Women. There were multi-generational conversations as well. A personal account of menopause sparked nearly two hours of discussion in a room filled with mixed ages (22-73), gender identities, and sexual identities. That discussion impressed upon me the critical and exuberant necessity of mixed-age encounter and exchange, and shifted my interest simply from “ageism” to “mixed-age encounter.”2 Think about it: how often does the opportunity present itself to be in a room filled with multiple ages engaging in conversation or shared activity?

View of the program space of M________ waiting for the first program of the day. Background walls display a menopause museum containing related cultural artifacts: among them a portrait of Edith Bunker, the first character on television to experience menopause. Photo: Nancy Nowacek.

Nam Phoang Dong shares her thoughts in a mixed-age group conversation about bodies and aging in M________, The Menopause Project, 2018. Photo: Nancy Nowacek.

Flyers designed by Nowacek were hung throughout Brooklyn advertising M________ in both English and Spanish. Photo: Nancy Nowacek.

A interior view of M________, The Menopause Project, 2018. On the far wall is a t-shirt by Macon Reed to “Support Crones,” a jump rope by Nowacek, and an etched mirror reading “Let Go of the Fantasy,” by Amy Khoshbin. Photo: Hai Zhang.

As part of M_________, the Menopause Project, Lindsay Cormack taught a workshop on Powerlifting as a response to menopause, and Lainie Fefferman reviews her instruction before attempting a dead lift. Photo: Nancy Nowacek.

Interior spread of Menopause: An Imperfect GuideI co-created by Nancy Nowacek and Sasha Davies, written by Sasha Davies, designed by Nancy Nowacek, and Illustrated by Kate Bingaman-Burt, 2018. Photo: Nancy Nowacek.

Though extended families demonstrate age diversity, family gatherings may be one of the few contexts in which people of very different ages seek to interact with one another. Our society has evolved to a place of siloed generations. (Please see Ashton Applewhite’s blog post “Let’s Climb Out of the Generation Trap” from June 29, 2021 on thischairrocks.org.) That’s partly an effect of the ways activities, institutions, and services are structured, but it’s also the growing effects of ageism and the disappearance of older folks from mainstream culture. Or worse yet, their erasure. Ageism, defined in 1969 by Robert Neil Butler, is prejudging a person based on their age. A contemporary example is the meme “OK boomer.” And ageism goes both ways. Younger folks, like the WACTAC teens, are also targets of ageism in the devaluation of their skills and ideas as young people. There are multiple impacts of ageism, including lack of social connection, loneliness, and lack of empathy and understanding between generations. When the value and benefits of diversity are sought, age diversity should be among them, because bringing different ages into contact with one another can build understanding and mutual respect, and improve the mental and emotional health of all involved.

When encounters are framed as age-diverse, the forms of power each group has or doesn’t have can be articulated, and the differences in experiences brought by age can be articulated, just as experiences from differences in identities, cultures, and backgrounds. That is to say, age-diverse encounters pose an opportunity to welcome the often not-talked-about part of who we are: our biological and our perceived ages, and all that come with them. If the best learning environments are those that invite the totalities of each participant’s identities to the table, so to speak, then age should also be a part of that. Imagine age-diverse group introductions: name, pronouns, biological and perceived ages.

Sharing personal experiences is integral to creating meaningful intergenerational exchange. WACTAC did that in some unexpected ways. The ice-breaker question for our last meeting was, “What is your favorite limb?” which turned into, “What was your favorite childhood injury?” which turned into a funny, gasp-worthy set of stories that created common ground for all of us. Their exploration of the power structures that make “Art” and “Artists” gave us a shared goal—another key to intergenerational work—but selfishly, I wanted more. I wanted some Deep Hanging Out.

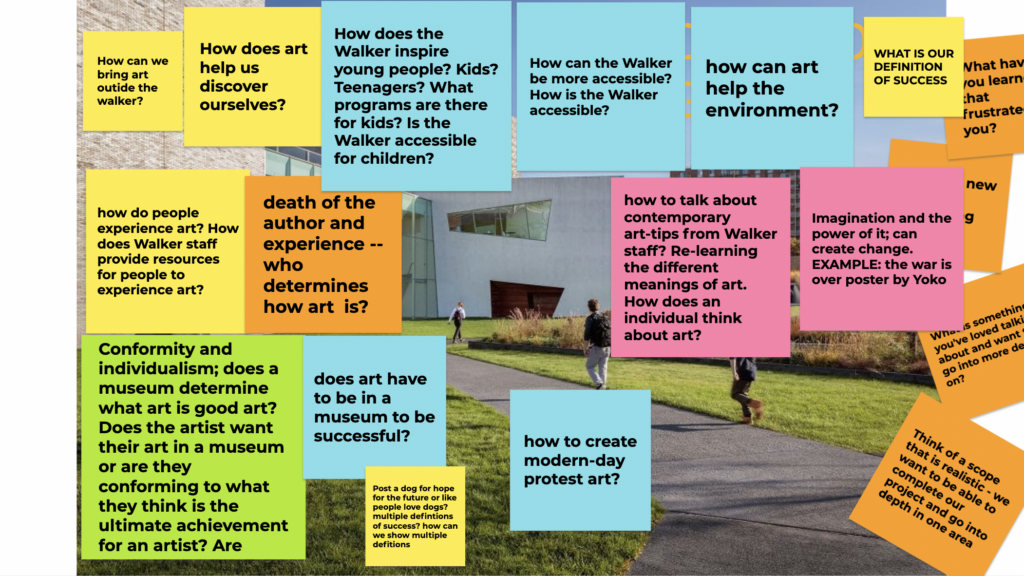

WACTAC’s process. Screenshot courtesy Simona Zappas.

WACTAC’s process. Screenshot courtesy Simona Zappas.

WACTAC 2020-2021. Photo courtesy Simona Zappas.

WACTAC’s process. Screenshot courtesy Simona Zappas.

Deep Hanging Out3 is a strategy and term I learned from the excellent organization Public Matters in Los Angeles. Deep Hanging Out is the sharing and learning that comes from taskless time together… i.e., snacking and chilling. Though the teens and facilitators, who met every week over the entire school year, found some good hangout time, my role as an every-few-weeks participant, dropping into weekly two-hour meetings with an agenda of three or four tasks, it was hard to find that sense of being with. I finally got a little bit of that at the very last WACTAC meeting, when we were finally able to gather in person. After a semester of cheering on the group through Zoom, it was deeply gratifying to finally meet them as people, with legs, feet, height, mannerisms, incredible style and magically colored hair—more literal and figurative dimension—that had been impossible to perceive virtually. We sat around and munched from a dazzling snack buffet curated by the facilitators. It got quiet for a moment, everyone lost in chewing. And then the request for an opening question for the group came: “What is your favorite snack and why?” An unexpected hit: chocolate-covered rice cakes. Together we crunched, marveling at the ability of a single snack to be vegan, gluten free, and super yummy.