ESSAY/FEATURED FORUM: Diary of a Crisis

Lightsey Darst chronicles the recent turmoil at the Southern Theater, but her nuanced essay offers insight into more than just this particular tumult. It's a good start to this month's featured forum on recent shakeups elsewhere in the art scene.

THE CRISIS BEGAN ON JULY 15. That day, The Star-Tribune broke news of Jeff Bartletts abrupt dismissal from his longtime position as Artistic Director of the Southern Theater. He was surprised, he said in the article. He didnt know why it had happened. Quickly, people in the dance community forwarded the article to each other. Bartlett was important. He didnt just book shows, he got involvedmost visibly by serving as lighting designer for most of the Southerns season, lighting shows with sensitivity and skill. Bartlett was the Southern, people said. An emergency meeting was planned for the day after the Stribs article; then a public meeting was set for Monday, July 21, with an invitation/demand extended to members of the Southern Board (who were, of course, behind the decision to dismiss Bartlett in the first place).

Actually, you could probably trace the roots of the crisis to as early as 2006, when the Southern racked up a big debt after renovations. Or perhaps you’d tie the current turmoil to more recent eventssometime this spring, when Bartlett and the (more or less) all-new board started to struggle over power. But Im not writing about the inside dirt here. Im writing about the middle view, the crisis in the dance community which depends on this arts organization. And for those of us in the middle, July 15 was when the crisis started.

Here’s how I remember it: I get the news via the University of Minnesota dance department. I admit my initial reactions muted. I know its An Event; I know Ill be hearing more about it. But I dont know Jeff Bartlett. Besides, I have this thing, this perpetual unwillingness to get involved; I dont sign petitions. So here I am, spectator to yet another scene of severe emotion, as panicked or furious emails fly through my inbox. It doesnt seem healthy to me, this voyeurism, but what am I to do? There are a lot of strong emotions in the world, and we can only really feel so many of them. I dont want to attend the Monday meeting; my weeks already packed. But the guilt-tripping emails begin arriving in my in-box: Please, please make time to attend this meeting, runs the one that finally gets me. So I go.

_________________________________________________

The community meeting about the Southern on July 21 is one of those rare occasions when you could take out the entire dance community at once, if you were so inclined: everyones here, from the postmodern floor-crawlers and the flowing-tressed ballerina queen to the modern veterans and the young hopefuls.

_________________________________________________

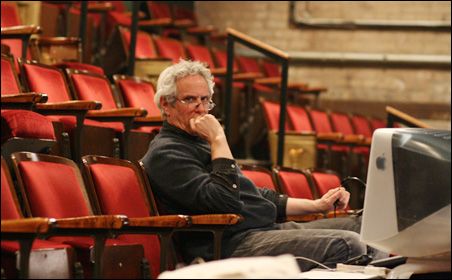

7:00, Monday, July 21, the black box at the U of Ms Barbara Barker Center fills up. Some people sit in a congenial-looking circle on stage; the rest of us pack the bleachers. Standing room only. It’s one of those rare occasions when you could take out the entire dance community at once, if you were so inclined: everyones here, from the postmodern floor-crawlers and the flowing-tressed ballerina queen to the modern veterans and the young hopefuls. Name a company; its represented. And the funders are here too: This Big Foundation and That Big Foundation and The Other Big Foundation. And the dance journalists, sitting in the crowd with the dance partisans, because were dance partisans too. And the Southern Board members and the new President/CEO are here, sitting in the congenial big circle, smiling like they have no idea whats about to happen.

Things start civilly enoughin the first five minutes. We have a facilitator who tells us when we can say what, and the beginning is reserved for introductions. The Board members proudly state their time of service18 months, 2 months, 2 years, 1 dayand the dancers come back at them with years performing3 years, 15 years, 20-plus years. Subtext: who owns the Southern, who knows more about whats best for the Southern? It doesnt take long for this subtext to come out in the open, and then its on, the war of words. First, the partisans: shouts and dignified speeches, fast quips and heartfelt pleas, and what they all have in common is an undercurrent of anger.

Theres a lot to be angry about. Bartlett wasnt just dismissed; he was abruptly ejected in a manner that could hardly have been more disrespectful to the artists who signed on to produce work under his aegis. Consider this: contracts havent been signed, but the season brochure went out the weekend of Bartletts firing, with the full years concerts, minus the usual letter from Bartlett. Given that the brochure must be prepared well in advanceyou dont just crank one of those things out the night beforethe Board must have known (or at least suspected) in advance that they were going to off Bartlett. But they didnt tell anyone, even after they let him go. The artists slated for performances this year at the Southern were left to read the news in the Strib. Admittedly, the Board wouldnt have sanctioned that leak, but what did they think would happen? In the Southern Board, clearly, were dealing with a group of people who will have to take on at least one negative adjective: if they arent nasty, conniving, devious, malicious, or arrogant, then theyre inept and naïve. Sorry, gangbut this was a big bungle. Theres no way around that.

And this, the artists are determined to let them know.

_________________________________________________

After all this, the Southern Board will have to take on at least one negative adjective: if they arent nasty, conniving, devious, malicious, or arrogant, then theyre inept and naïve. Sorry, gangbut this was a big bungle. Theres no way around that.

_________________________________________________

Responding, the Board members are a mix of sad, defensive, and condescending, but they have a keynote too: they cant say anything. Sometimes this takes the form of Orwellian gobbledygook, as in this sentence from a pre-meeting press release titled Southern Theater in a Strong Leadership Position: “Throughout this process [of changing the structure of the Southern], Jeff Bartlett was given multiple opportunities to give feedback, participate in the discussions, offer solutions, and ultimately embrace the new organizational structure of the Southern Theater by actively participating in harmony with the new organization.”

When youre given multiple opportunities to embrace something, you know the writings on the wall. Were also treated to absurdist legal exchanges, like this nugget:

Board Member [deflecting a question about the reason for Bartletts dismissal]: We dont have a legal release to discuss that.

Dance Partisan [wielding a laptop]: I just got an email from Jeffs lawyer saying you havent requested a legal release.

Board [with a snort]: Well, we could request a release, but Im sure we wouldnt get it.

Partisan: But will you request a release?

At such times it seems there must be something really shocking the Boards keeping from us. In the words of one partisan, Youre making it sound like he molested children! Whatever the reason, its clear that hes out for good; the Board does not remotely entertain the idea of Bartlett returning.

Why was Bartlett let go? Everyones best guess: the Board said, Heres how its going to be, and Bartlett said No. And how did they say it would be? After several capitalized-sounding utterances about New Plans, and a handful of vague references to Bartletts legacy, someone gets down to specifics. The Southern will now have three curators (for dance, music, and theater) and one President/CEO. Im spurred to ask my one question of the night: If there are three curators, does that mean dance will no longer come first at the Southern? Answer: Dance will remain the Southerns chief focus. Oh! All right then. I feel comforted. Its a comfort that wont last long.

As for the middle of the meeting, once the partisans have said that theyre angry and the Board has said they cant say anything muchi.e., once an impasse has been reachedwell, what follows is a truly classic hour-and-a-half. I take notes. Here, a little chopped and edited, but generally verbatim, are my notes from the middle of the meeting:

Approach this conversation beyond tonight, by having & feeling

the importance: tried

a new strategic vision. I know the function. You want us to

see the element of humanity; future; we are convinced / in feet,

expand. Step

forward. Plans are potentially / the only plan

are being considered are what you see beyond that the only plans.

Division built upon needs to be built upon need to be careful. It

seems

very very simple! Model viable, motivating / landscape & market /

where everyone

can flourish, share a thought, a strong collective sense. Part

home. Let me

understand this (information exchange). Youre right on. Bring /

Reportget

everything very smoothly. what about a visionary? Specific /

inability to talk. Question we cant comment. We struggled

mightily / legal representation /

Things happen. and its painful and its difficult. I understand

it doesnt matter what I say.

In the last thirty minutes, things again become interesting. An expletive-laden burst (as the Strib will have it the next day) from a dance partisan sets off one of the board members. Shes been whispering angrily to her neighbor for a while, and apparently the f-bomb she hears is just too much: she sits up straight and delivers herself of a screed that, in my defective memory, now comes from the mouth of Megan Mullallys shrill Will & Grace character. I dont need to be treated like this! Ive given over 100 hours to this Board! Ive got a husband and children to go home to! We all sit back in shock. You have children? More than one? And you can still afford those shoes?

_________________________________________________

One board member sits up straight and delivers herself of a screed that, in my memory, now comes from the mouth of Megan Mullally’s shrill Will & Grace character. I dont need to be treated like this! Ive given over 100 hours to this Board! Ive got a husband and children to go home to! We all sit back in shock. You have children? More than one? And you can still afford those shoes?

_________________________________________________

But its the 100 hours that bring me up short. I was in a Fringe show this summer, which, between rehearsal and performance, probably occupied 50 hours in three months (not counting transit), and, like a lot of local dancers, I wasnt paid for my time. But it would never have occurred to me to tote this up, because I know thats nothing. 100 hours? Welcome to the party! 100 hours? That and a quarter will get you on a bus that you probably dont even know how to ride!

Another outburst is more informative: a dancer, her pleading arms evocative of Greek tragedy, tells us that she saw the numbers, that the Southern would have been no more if it werent for the actions of the Board. I wasnt supposed to know! she says. But she did know, and now shes telling us.

But why wasnt she supposed to know? Why couldnt the Southern have told us all? If wed known the Southern was in big trouble, wed have had a bake sale. Transparency, please. Sure, artists are stupid about money, we couldnt have understood it if wed been told, etcyou can haul out those lies, but its shocking how dancers manage to keep themselves fed despite not making any money to speak of. Does the business side of an arts nonprofit exist to keep the pretty people blithely unaware of the real worldeven when the pretty people want and need to know whats going on? Shades of Jack Nicholson: You cant handle the truth!

Finally, a mealy-mouthed but well-intentioned young woman offers up some closure, extending thanks and understanding in all directions. When she gets to the Board, howeverand we respect you and what youre doingan irate partisan cant take it anymore, and he snaps out the zinger of the evening: I dont respect the Board!

When, now past 9:30, its over, we applaud our facilitator with the deranged enthusiasm Im told prisoners sometimes show for their captors.

Q. What did we learn from the meeting?

A. The Boards made its decision, and theyre not willing or able to talk about it.

Q. What else did we learn from the meeting?

A. The dance community wont take this lying down.

Q. How will they take it, then?

In the days afterwards, outside the meeting hothouse, peoples opinions are more complex, less monumental. So what did you think of the meeting? people say, smiling, or, We need to talk about the Southern thing, they might hiss, on the verge of unloading a conspiracy theory. Private opinions and experiences dont always match up with public statements: a seemingly staunch Bartlettian betrays secret amusement at the circus; a vocal supporter turns out to have had Bartlett problems (at the time, I thought, Wait, I havent seen your work at the Southern in years!); an artist who sat still and silent at the meeting most passionately speaks for Bartlett in a tête-à-tête at a café.

Some people certainly stay right on the tone of the meeting, among them one longtime partisan, who develops the charming habit of hitting “reply-all” when responding to what appear to be private emails regarding the controversy. Each of his missives is a fist-pounder, suitable for analysis by high school oratory classes. He closes one such message with this stinging peroration: They [the Southern Board] will have to call me before I call them. They will have to explain before I have to ask. They will have to apologize first. But, my friend! I want to exclaim. They are never going to call you! They have no bleeding idea who you are!

Among the dominant pro-Bartlett strain, I hear a few less flattering voices. Bartlett burned a few people along the way (artists whose phone calls he wouldnt return, etc), and theyre enjoying some schadenfreude at his expense. Egomaniac, someone says.

In this cacophony of voices and opinions, Bartlett seems to be losing his selfhood, his familiar nervous smile spreading out into a void, his name becoming a word. Was it Bartlett that brought a whole steaming dance community together? Or, was it Bartlett-plus, Bartlett and a way of doing things he representsthe Old Way, the friendly, informal, artist-dedicated way, without a lot of fancy theater amenities (online box-office, etc)a way also represented by the Southern itself, with its peeling-paint interior and rugged unrestored arch.

Amid this talk, the crisis goes on. A boycott looms: the artists of the 2008-2009 season are talking about pulling out. They need to hear from Bartlett: Does he want them to protest? Will it do him any good?

A petition makes the rounds: Springboard for the Arts will pony up the money for an independent evaluator, and we, the undersigned, would damn well like you Board people to indicate your willingness to comply by August 14 (I grotesquely simplify). I dont sign itfear of commitmentand the next day its published with a slew of names. Instantly I feel bad. When are you going to stand up, if not in a crowd of justifiably angry artists? When are you going to stand for something? But Im hardly alone.

Others, just as gun-shy, arent willing to be swept along on a wave of ill-informed indignation. Another know-nothing controversy is someones verdict. Indeed, we know nothing. But faith in Bartlett propels many forward. Anger at the Board is another motivator; mistrust of any executive power that holds itself above artistic power propels another mass. And despite my non-signature, Im feeling myself pulled along with this last group. And I’m swayed because, as I find myself explaining over breakfasts, coffees, and cocktails, with increasing vehemence, this three-curator model disarms the artistic side of the Southern. The three curators will compete for the Presidents approval; theyll have no leverage. I dont know much about big non-profits, but I have a strong sense that the artistic and executive powers ought to be balanced. After all, art is why these organizations exist.

And then suddenly, on August 13, two letters (dated August 8) go out to the Southern Theater’s email list: one from the Board Chair, and one from Jeff Bartlett. The Chairs is predictable, nothing new, but Bartletts (if equally predictable) seems to settle the deal. Read it for yourself here. Basically, he says, Thanks, gang, but no thanks. I signed the papers; Im out.

Utter silence on my email.

Is the crisis over? Bartletts statement is all legalese, someone says, and we should be aware of that. Okay: what should we do with our awareness? Is protesting Bartletts dismissals a dead letter now? I hear nothing about the fate of the petition. I hear nothing at all.

So I start writing. And I call for helpwith the view from the middle ground a hopeless haze, I need illumination from the inside. Forget the soup of personalities, the who-said-what. Not that theres nothing to say about S. B. et al, theres plenty, but that kind of unraveling depresses without enlightening. What I want to know is whats going to happen?

Its not over. I wish, sighs my source. The 2008-2009 artists are still talking about a boycott. The Southern refused Springboards offer of an evaluator. The artists are just going to have to trust them, they insistbut its a trust the Boards done nothing to earn. On September 6 the Southern is hosting an open meeting; by September 15 the artists will decide whether to stay in the season or not. My source describes this as a lose-lose decision. Working with the Board feels like crossing a picket line. Abandoning the Southern makes a statement, but thats all. It does no one any positive good.

My source confirms my intuition about the structure of arts organizations. A natural healthy tension is necessary, a balance between artistic risk and the bottom line. Bartlett could have used a stronger executive to creatively butt heads with, probably; but, now, the Southern is all executive.

What does this mean for the future of the Southern? Heres where it gets dire, because Bartletts ouster isnt just a sample of executive power run amok, and then back to business as usual. In other words, it isnt just a matter of principlefiery at first but easily forgotten. My source sketches a disaster scenario. The bigger companies, held at the Southern primarily by their relationship with Bartlett, will leave for the Lab and the Schubert (set to break ground this fall), which have larger spaces where they can sell more tickets and make more money. The Southern will be left with smaller companies and independent choreographers, groups that a more financially conscious theater wouldnt want anyway because they cant pack the house. Bartletts legacy of a theater for local dance fails, and the independent artists he boosted between bestsellers have no comparable theater to fall back on. I dont want to be cynical, says my source, but we could be looking at the end of an era.

What next? If September 15 brings news of a boycott, everyone will watch the Boards next moves. How will they regroup? How will they approach the community? But if on September 15 you hear that the Southern season will go on as planned, dont mistake it for happily ever after. If the artists go on with their scheduled performances, theyll be doing so as a tentative act of faith, and theyll be doing so in honor of the last Southern season Bartlett curated.

Going into this crisis, my main concern had been whether the Southern programming would become more conservative. I hadnt always agreed with Bartletts vision, but I respected the fact that he had a theater to run, and I liked the Southerns programming enough that Id guess at least half my articles and reviews feature Southern shows. My first thought was that I didnt want to lose my go-to theater.

But I hadnt realized how delicately the Southern was balanced, or how big a change Bartlett’s dismissal might portend. I hadnt realized that I couldnt lose my go-to theater without everyone else losing theirs. Perhaps, still, itll all blow over: the Board will shape up, the artists will perform and find they can work with the new Southern management. I hope so. But whatever happens, I wont forget what Ive learned about the frailty of the moment in the arts. Look around: half of what you see will be gone in twenty years. The other half, well have to fight for.

In the midst of the crisis, the Fringe show I was in opened at the Southern. In my limited Twin Cities performing career Id never stepped on that great stage, and there I was, dumping my stuff in the dressing room, slumping in dancer schmattes around the inside of the theater, at precisely the moment when people were most inclined to say, Its just a spacethat a Bartlett-less Southern is just a venue.

Is it true? Are theatrical spaces just spaces? I dont know how to answer that question. Visit PS 122 in New York and you will get a yesthat low-ceilinged room, with its poor sightlines and two obstructing columns, is surely nothing special on its ownand a no, because its not just any low-ceilinged room, its PS 122. Like a church, a theatrical space becomes hallowed, and that hallowing is not a light switch you can flick off.

Nowhen a theater goes dark, youll feel the long-drawn pain.

About the writer: Lightsey Darst writes on dance for Mpls/St Paul magazine and is also a poet and editor of mnartists.orgs What Light: This Weeks Poem publication project.

FEATURED FORUM: Summer Shakeups: What Do These Changes Mean for Minnesota’s Art Scene?

From the turmoil over Stewart Turnquist’s departure from the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program (MAEP) at the Minnapolis Institute of Arts to the kerfuffle over the resignation of Minnesota Museum of American Art’s director, Bruce Lilly to the recent closures of the Minnesota Center for Photography and Theatre de la Jeune Lune–this summer has been a tumultuous one for arts organizations. WHAT DO YOU THINK? Weigh in with your own thoughts on what all this turnover means for Minnesota’s arts scene in this month’s featured forums.