Dress-Up: Windfarm at Rogue Buddha

Lightsey Darst saw Catalyst and Mad King Thomas perform dance-like things at Rogue Buddha Gallery in Northeast Minneapolis. It had its points.

Lately, it seems that everyone wants to get dressed up and play with toys. Dancers, I mean—at dance events around the city, fishnets, Pepto-Bismol-pink cakes, Batman masks, cordless drills and other power tools, vintage hats: all are making their appearance, wielded and worn by the dancer-mannequin, who might adopt a bland expression while chewing suggestively on a wad of gum or smile 1950s housewife style while dishing up slices of the aforementioned radioactive cake.

A very interesting person I spoke to a few nights ago called this “dance’s love affair with the theatrical,” her voice taking a disapproving hop over “theatrical”. This VIP has a point: dancers do love transformation and they do love grand entrances (bursting through the gallery’s back doors in a vampy forties get-up that makes everyone gasp). Dancers like to pose and they like to try things on; all that time in front of classroom mirrors has some effect, eventually. But the heart of what this VIP is saying is that dancers like, sometimes, to escape from dance, keeping it somewhere in the background like a poorly behaved or possibly deranged cousin while they pose, and talk, and mess around with stuff. And her critique is that we want dancers to do what they and only they can do: dance.

Generally, a little more listening to this voice of reason would be a good thing. The raids on thrift stores, the proliferation of blank looks, the non sequitur prop played for laffs—it’s all becoming a tad predictable. And yet it can be done well. Enter Windfarm #2, part #2.

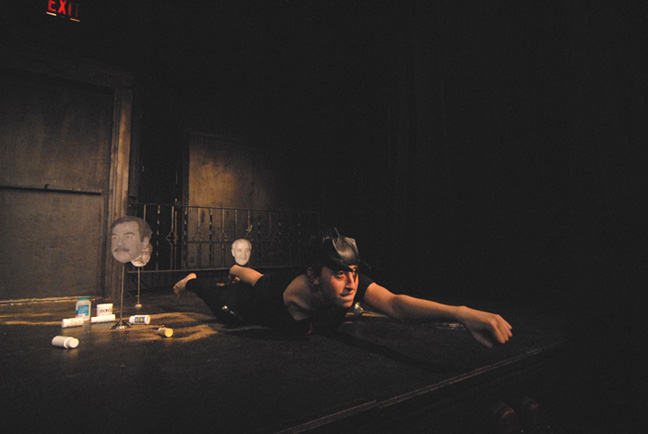

Emily Johnson’s “Pamela” calls itself, on one of the slightly Gorey placards that appear during the show, “a metaphysical rehearsal.” I can see that. Johnson, Hannah Kramer, and Jessica Cressey (who looks lately, and I mean this as a compliment, as sparkly as if she’d been eating babies) stalk and crawl and creep around in black vintage, moping over dead flowers, pushing the scenery around, and butting up against the walls. Kramer lies back on a couch and raises one vintage pump in the air, then, later, repeats the gesture—bored Weimar sexuality. Johnson turns her ascetic face up and blinks her eyes rapidly in a bled dry ecstasy, someone’s idea of a nun’s idea of orgasm. Or there’s the piece’s most repellant moment: Kramer wanders around in a black scarf and black glasses, Jackie O style, repeating “I’m so sad today” in her most meaningless soprano.

The name—“Pamela,” Pamela Anderson Lee, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded, Pamela the do-me pump—is redolent of false sexuality and melodrama. If three sisters were locked in an attic for twenty years, perhaps their lives would look like this. The entire piece feels like one of those wretched letters or journal entries that adolescent girls write, full of made-up emotion, grief and desire and romance without object or experience.

But I forgot to mention the dance. There are hints of it. And if there’s nothing in the moping and vamping but the desire to mope and vamp, there’s something in the dance. Clumpy, awkward, Johnson’s movement is utterly at odds with the dresses and pumps the women wear, and feels at first affectless, unrelated, until you begin to see the dark rage at the center of it. Self-hatred, maybe—the curvilinear feminine body forced into straight lines—or just motiveless anger: tantrum dance. It turns out there was something in that adolescent letter after all, nearly smothered in the forms offered for it, but burning there at the heart.

Mad King Thomas is a completely different kind of animal. Mad King Thomas is the kind of animal, in fact, that you used to make by folding a sheet of paper into thirds and drawing the head on this portion, the torso on this, and the legs on that. (Even the group’s name is a compound: the performers are Theresa Madaus, Tara King, and Monica Thomas.)

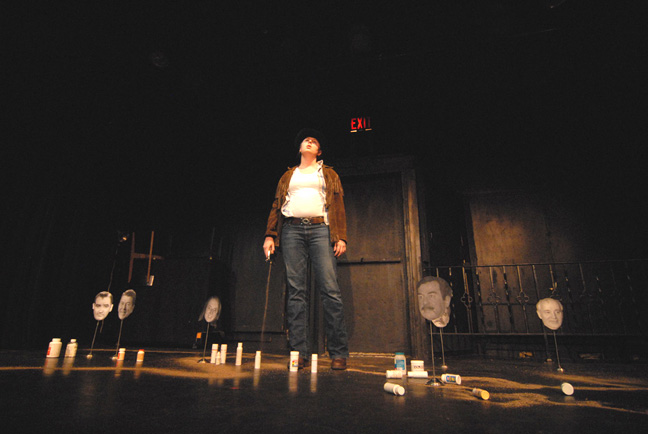

If in Catalyst’s latest dance is the dark matter holding together the frippery of the visible universe, in Mad King Thomas’s “Cover Your Head and Kiss Your Ass Goodbye” dance is a condiment—perhaps mint jelly, on the table for its color more than anything. Also on the table are plenty of objects—toy soldiers, a cake, a TV, heads of world leaders on sticks, sand, a bowl of ice—assorted shenanigans with objects, talking, and some clever stage images. We don’t even have to call Mad King Thomas dance, if anyone had rather not; let’s leave the bother of categorizing it to scholars (who seem to like that sort of thing) and simply enjoy it.

And it is enjoyable. I winced when I saw the endless props being set up, the oh so thrift outfits, but I’m pleased to report that Mad King Thomas actually works with these absurd items, creating effects sometimes wildly funny and sometimes poignant. Wildly funny would be the Starboy sequence, in which we are told to open and shut our eyes while two performers go through the stop-motion poses of a conventional hero story; also the horse-race-cum-line-dance performed with the heads of world leaders (I’m sorry, I can’t explain it any better; you had to be there). MKT achieves poignant effects with an array of toy soldiers lit up by flashlights, their fuzzy, triple-outlined images projected against a white wall; over silence, the still figures slide across the wall, going through the motions of battle.

“Cover Your Head,” as you might expect, evokes the dread of nuclear or other catastrophe, but there’s also a strain that explores the construction of heroism somewhat sympathetically, which is a welcome touch and more interesting than your standard take on nuclear war. No great thesis is achieved here, but that’s fine; “Cover Your Head” is well-woven and smart. There’s a bit of clutter (the cake and TV), and I worry that MKT buys into the faux heroism of Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start the Fire,” the singer’s self-dramatic “I can’t take it anymore!” But by the end MKT turns this outcry into a calm little endurance test, one performer’s hand in a bowl of ice cubes, a milky sweet smile across her face. We can take it, of course; that’s the scary thing.

On the way home from Windfarm, after all that posing and object-play, I switched off 99.5’s Mstislav Rostropovich marathon in favor of early Madonna. Strangely, I felt like dancing.