Dancing a Bridge: New York City Comes Uptown

Critic Lightsey Darst reflects on the dance collaboration extravaganzas, featuring work from NYC and Twin Cities performers, that have been gracing the stages of both the Bryant Lake Bowl and the Walker Art Center this month.

Building a bridge

“It’s a bridge that’s been built and crumbled and built and crumbled,” says Kristin Van Loon, dancer-choreographer with the avant-garde duo Hijack and director of the Bryant-Lake Bowl theater. She’s talking about the New York-Minneapolis dance bridge, which has been especially important this past month.

Here’s the conventional wisdom about the relationship of New York to Minneapolis: New York sucks up talented young people and spits them back at us in the form of touring performances. All the best dancers and choreographers are in New York, because if you could make it there, you’d be there.

The reality is more complicated. New York is still tops in the performing arts, such that a show’s New York provenance weighs heavily with presenters and audiences. And New York is still a noted firing-ground for artistic souls. But those artistic souls, once fired, now feel more freedom to choose other places to work, as evidenced by the number of one-time New Yorkers who’ve settled in Minnesota’s balmier financial climate: Stuart Pimsler Dance and Theater, James Sewell Ballet, Karen Sherman, Linda Shapiro, et al. Plenty of dance artists carry on complete careers in Minneapolis, with no desire to “try New York.” Is the sense of provincial inferiority still there? A little bit; the amount varies depending on the dance form. But beyond the simple curiosity that artists anywhere express about any other art scene, what I hear most is that Twin Cities’ dancers miss the national exposure that can attend a New York performance.

For those Minnesota performers with ambitions to take their shows out East, you might think the density of former New Yorkers residing here would make it easy for Minneapolis artists to get to NYC. But it doesn’t work that way. Getting a booking, gathering the money to get a company to New York, being taken seriously by the New York press—all these have been stumbling blocks for local artists. But one dance form is making the connection, albeit under the usual radar.

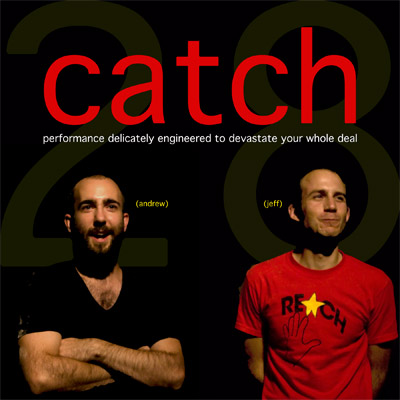

Like all dance-artists, avant-garde/contemporary performers are brought together by festivals, classes, and the occasional tour. But because these artists have seized the means of production, presenting each other in cabaret-style shows at small venues, they can offer one another more assistance than, say, ballet dancers can. A night at the Bryant Lake Bowl, ground zero for the avant-garde scene locally, means drinking, eating, laughing, talking, and a variety of short dance pieces, all cheered on by dance-scene regulars. New York’s Catch series (curated by Jeff Larson and Andrew Dinwiddie) is similar. Catch and the BLB can’t usually afford to show out-of-towners (the performances don’t bring in much cash), but they certainly keep out-of-towners in mind. This month, the Walker’s Out There series offered a chance that Van Loon, Larson, Dinwiddie, and Minneapolis’s BodyCartography Project seized. With the two large casts of Miguel Gutierrez’s Everyone and David Neumanm’s Feed Forward here on the Walker’s dime, “it just finally all came into alignment,” Dinwiddie says, to share New York work with Minneapolis audiences in two BLB performances, one on January 6 and another January 27. When the opportunity arises, Minneapolis dancers will similarly take over Catch in New York City.

Crossing the bridge

Three performances later (after the two BLB shows and Miguel Gutierrez’s Walker show), how goes the New York invasion? What new sights could we see?

After taking in the first BLB performance of the month, I came away with a distinct impression of difference. Minneapolis work can be diffuse, with any particular program or idea hidden under the entertainment, or the persona of the dancer, or perhaps dissolved entirely by radical politics that question the nature of meaning and artist. Conversely, the NYC work felt more experimental in the scientific sense of the word: more programmatic, more specific, its ideas more rapidly gleaned and lending themselves more clearly to reviewing and history-writing.

Daniel Linehan’s excerpts from Not About Everything, in which Linehan repeats “this is not about everything” and a laundry list of other things that the performance is “not about,” clearly questioned the good of artistic work. And, despite his assertion that “this is not about endurance,” it certainly is dependent on staying-power, his and the audience’s, as he spins in a circle for most of the piece. This sort of work is entertaining enough in the moment, making the audience feel clever for getting the underlying content; but on reflection it feels thin and young. Unfortunately, Gutierrez’s Walker show, Everyone, though more substantial and more interesting in its surface construction, ultimately suffered the same “got it, done with it” fate in my mind. On the other hand, I’m still mostly loving Christine Elmo’s solo number one, seen at the January 6 BLB performance. Elmo plays pretty obviously with privilege and disclosure, walking about in her leotard, making ballet arms leaving us to catch only snippets of her through a barely-parted curtain. But the image she constructs remains long after the concept’s been “got”. Elmo’s smoky sex appeal, half-seen, memorably incarnates that fascinating archetype, the crush.

“You’re not developing technique and precision, you’re developing ideas and show,” Jeff Larson said when I asked him about making dance in New York. The pressure-cooker of competition for time and money forces artists to be clear about their niches and the stages of their development. Performances that come to the Walker from New York often have hooks, angles, innovations—something for audiences and the press to grab onto.

But my impression of New York work as idea-driven faded a bit this past weekend, at a BLB show which featured New Yorkers alongside Minneapolis BLB regulars. In this performance the differences between the two regions’ styles weren’t so clear-cut. “I feel a great kinship” with Minneapolis work, Larson told me; and this kinship was especially evident in straight-up dance pieces by Anna Marie Shogren (Mpls), Justin Jones (Mpls), and Chris Yon (NYC). All three showed precise movement that seemed to create its own language for emotional states—not a mimetic language, not an exalted language, as in romantic ballet or early American modern dance, but a kinesthetic language capable of expressing the subtlety and variety of daily emotions. Yon’s Hugo looks like life to me—life translated, but neither idealized nor trivialized, which I find a particularly interesting achievement. The similar style and effect isn’t coincidence, though: ex-New Yorker Jones used to work closely with Yon, and Jones has certainly influenced and been influenced by our scene (and Shogren) since arriving here. With Yon moving to Minneapolis this summer, we’ll certainly see more of this type of dance.

Still, in this most recent performance the idea-centricity I noticed in the earlier Walker and BLB shows this month persisted, though in a slightly different form. While Minneapolitans Mad King Thomas and Erin Search-Wells threw the kitchen sink into works that looked as if they needed a few more hours to expand to full size, New Yorkers like Andrew Dinwiddie, Matt Citron, Neal Medlyn, and others followed narrow branches of inspiration to their very tips. These focused NYC performances also pursued theater in a more brazen way than Minneapolis dancers, so far, seem comfortable with. Dinwiddie’s recreation of a Jimmy Swaggart speech was my favorite. I found myself experiencing Swaggart’s surprisingly intelligent preaching through Dinwiddie’s full-throated and full-bodied performance, sans irony, sans modern commentary. Obsessive, yes; not exactly dance, maybe; but it’s an absolutely concentrated experience all the same, with the artist’s desire to show you the rest of his talents and influences refreshingly reduced to nil.

I suspect the New Yorkers’ narrower focus might assist them in gaining press coverage (not to mention those big Walker gigs, like David Neumann’s Feed Forward, which opens this Thursday). Some Minneapolis artists could certainly benefit from greater concentration in their work. But the primary impression left by these performances isn’t one of intellectual difference in approach and execution, anyway. Instead, most striking is the clear pleasure of dancers and audience in seeing each other, in having made their own connection across the country.

For Kristin Van Loon, the chance to see New York dance isn’t about hierarchy but simply about difference. These days the Internet and other media have turned the world into one backyard, so that artists anywhere can be acquainted with their counterparts anywhere else. Even so, dance remains profoundly local, and you’ll understand why when you consider how much dancers rely on each other: as collaborators, teachers, students, roommates, etc. For example, Van Loon tells the story of seeing a Chicago dance festival and realizing that at that time in Chicago, dancers often initiated movement from their fingers; while, in Minneapolis, movement came from the core, with the arms and hands following. Dance from elsewhere offers new choreographic possibilities. Van Loon hadn’t seen all the NYC artists before presenting them; instead, she was enthusiastic about “that leap of faith that I take—and that I think is a great thing to offer audiences.” In this performance network, there’s also “that other leap of faith—[out-of-towners] can have my apartment for a night” before the Walker’s expense account kicks in. Let’s hope it’s not too long before someone will return Van Loon’s leap of faith, allowing Minnesotan artists similar entry into New York’s dance scene and solidifying this new bridge.

About the writer: Lightsey Darst writes on dance for Mpls/St Paul magazine and is also a poet and editor of mnartists.org’s What Light: This Week’s Poem publication project.

What: David Neumann’s Feed Forward

Where: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

When: Performances run from January 31-February 2

Tickets: $20 for general admission (discounted tickets for WAC members)