DANCE: Something in the Way She Moves

Performance maven Lightsey Darst looks into the artistic heart of the dancer, with a revealing profile of McKnight dance fellow Laura Selle Virtucio (one of the featured soloists in the upcoming show, SOLO, at the Southern Theater July 11-13).

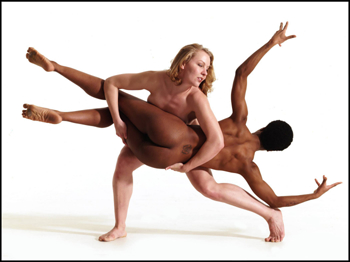

LAURA SELLE VIRTUCIO LIGHTS UP THE STAGE: she has a generous presence, strength she can modulate from explosion to feather with catlike grace. Lines hang in the air after shes moved on, as if they were there all along. You dont forget Selle Virtucios dancing. Shes memorable, too, for her distinctive formtall, but not the typical leggy, willowy-tall dancertheres no mistaking her for immaterial. She has a heroic build, more like a Michelangelo than a Gothic saint or a Baroque siren. Or, more like da Vincis Vitruvian man: like his, her movements reveal an order, a physical and emotional geometry that seems right and familiar at the same time that its startling and new. No wonder shes in such demand, dancing for Stuart Pimsler Dance & Theater, Shapiro & Smith Dance, and Carl Flinks Black Label Movement, along with many independent projects like Eddie Oroyans upcoming Momentum work, Brown Rocket (July 24-26).

Selle Virtucio, along with the five other McKnight dance fellows from 2006 and 2007 (Karla Grotting, Colette Illarde, Abdo Sayegh, Tamara Nadel, and Mifa Ko), will be performing the solo created for her as part of her fellowship from July 11 to 13 at the Southern. This occasion struck me as an ideal opportunity to learn more about dancersso visible and yet so often critically overlooked in favor of the choreography they performand as an ideal opportunity to learn more about this one exceptional dancer, in particular.

First, I wondered if Selle Virtucio, so distinctive in shape and style, ever wishes she were a different type of dancer. Im not a real leggy, long-extension, flexibility kind of dancer, she admits. And before she knew much about modern dance, she worried she would have to conform to the balletic model if she wanted to be a dancer. But now I feel more confident, she says. Each dancer has such specific strengths and weaknesses. What I lack in lightness, I make up for in bounding strengthand I can pick up the guys I dance with! Its not just that Selle Virtucios found her own strengths, though: Ive learned to morph and puzzle-piece and problem-solve.” She can put herself into “that little girl role if she needs to, by imagining her way in; or, she can lengthen the line of her leg by stretching through her torso so the same feel or essence comes out. She offers words that should cheer any less-than-tiny dance student: she now has no qualms about not being that small, petite dancer.

Speaking of students, what qualities do young dancers need to have or develop in order to become professionals? Selle Virtucios answers arent what you might expect. First, Theres something about the imaginationbeing able to get caught up in the story of a work right away. Watch Selle Virtucio in Joanie Shapiros work, for example, and you see a rich inner life rippling through her dance, a life that encompasses her fellow dancers. Most of the work I do demands for someone to be real on stagealive, alert, in an emotional and not a purely physical stateand to work with the people in the space as humansrather than as automatons. There are very few students who have that ability to connect.

Second, she says, is definitely desire. You have to be physically hungry somehow. There’s a need to move, a restlessness, that Selle Virtucio thinks is in everyone, but which is highly developed in some. But the requisite desire goes beyond the physicalyou also need the desire to be an artist, to say something to somebody outside your little community.

Finally, oddly enough, just being a good person, being able to have conversations and engage in thought and discussion. Ive heard similar words from other dancers. Dance is highly collaborative, and dancers need to be able to be present, to offer and accept suggestions. These are skills that other types of artists (writers, visual artists) sometimes pride themselves on not having. Actually, this is not the first time Ive been struck by the emphasis on health (of all kinds) in dance, and by the necessity for the dancer to work on all parts of him or herselfabout which, more later.

But Selle Virtucio doesnt mention talent, so I ask her: does an aspiring dancer need to be talented? I dont know that I ever really felt I had a talent for dance. I hate to comment on technical talent, because I dont know what that is, she demurs. Its different for each person and each choreographer. For Selle Virtucio, the dancers physical ability is only one component, and she considers it easier to achieve the necessary physical skill than to achieve the performative skill, the imagination, or the ability to collaborate. If you only have that (physical ability), youre out of luck, she says. More important is learning to use the skill you have, to infuse it with spirit. Being a good performer is so much more than getting your body in the right places.

Her own dancing, skilled as it is, bears this out. In all my visual memories of Selle Virtucio, shes mid-air, so naturally, I think shes an extraordinary jumper. But when I watch her closely, I dont see preternatural hang-time or elevation. Its the feeling Selle Virtucio gathers into her jumps that makes you think shes in the air forever.

I kind of think everyones a dancer, she muses. She cites her experience with Stuart Pimsler Dance & Theater, known for work with people with disabilities. We make dances with stroke survivorspeople who maybe cant speak or use their right arms at alland theyre beautiful dancers. Ive seen so many different types of people do work that moves me.

But what do dancers do, exactly? We have a basic understanding of what independent creating artists, like painters and sculptors, or writers and composers, do. They bring a vision of their own into the world through their chosen medium; or, simply, they make things. We also understand what repertory artistsclassical musicians, stage actors, or (for most of their careers) dancers at big ballet companiesdo: they interpret. They take a work by Mozart or a Sleeping Beauty variation and try to find their own version of it. But what about non-repertory dancers like Selle Virtucio (and most other local soloist dancers)? Selle Virtucio originates roles, roles which are created on her, with her collaboration, but which are not under her sole control (she has no ambition to choreograph). Where, then, does the creative responsibility lie? How does she think of her own work?

Trying to answer these questions, Selle Virtucio struggles through a painting metaphor. The choreographer is the painter, the dancers are the paint, but the paint is aliveso she switches over to paint-by-numbers, in which the choreographer brings the dancers into that space of his or her vision and we help color. Over time the dancer learns what the choreographer might want, and the choreographer learns what the dancer might have to give. And, at least in the modern dance Selle Virtucio does, choreographers want dancers who have something of their own, in particular, to give.

So, were back to the idea of the dancers total involvement in the dance. The dancer brings not just a body, but an entire personality to work. And thats not all: the personality, as expressed through the body, has to be magnetic, complex, unique. So I ask Selle Virtucio a question thats been percolating in my mind for a while: do dancers have to become, themselves, works of art? With a moments hesitation, she agrees. The people I dance with, who I think are amazingtheyre all works of art to me. She cites Mathew Janczewski (ARENA Dances choreographer and fellow Shapiro & Smith dancer): He has a way about him, a charm in his movement, in his emotional presence. Indirectly, she agrees that its true of herself as well. Its very rare that Ive not been asked to just go with it and make my own choice. Choreographers know thats when theyre going to get you at your peak performance, if youre heart and soul and body has dug into something. And the dancer must be able to show that heart and soul and body. You have to have some kind of master instinct that youre not afraid to just put out there.

For most of us, thats a scary idea. For dancers, thats life.

Lest you get the idea Selle Virtucio is some kind of self-proclaimed dance sage, she doesnt normally spend too much time thinking about all this. Its weird to verbalize some of that stuff, she says. I truly do just try to be on stage and to be in my life, and let the instinctual thing take over. Its the upcoming solo performance that’s prompting this kind of inquiry in her. The McKnight is a big award, and Selle Virtucio feels self-conscious about winning it and about performing her subsequent solo for an audience full of other dancersall the people who deserve the award as much as you do. Even more, she feels pressed by the question: whats next? Ive just been going with the flow, and the flows got to a point where I have to start choosing.

To choreograph her solo, Selle Virtucio chose New Yorks Colleen Thomas (whose visceral work was seen last year at the Southern Theater and in Zenons fall concert this year). Ive worked with the same people for the last nine, ten years, she says, and while shes not planning to quit any of her current jobs, she wants to reach beyond herself for her solo. In particular, she wants to try a different approach to emotionsomething that has the potential for lightness rather than this really dramatic, romantic thing that she often finds herself doing. Also, she wants to push her acting to the side and let the dance speak for itself: to find a way for some of the movement to just be movement, movement that, because Colleens a good choreographer, just says something with its essence. The resulting solo, Can You Look Me in the Eyes, is a departure. Its far more postmodern than Selle Virtucios usual work, with abrupt switches of music and movement style, irony, and a rubber chicken.

This brings up the question of typecasting. To some extent, Selle Virtucio does find herself typecastalways the strong one, always emotional, rarely just a physical presence. But she tries to work with people who can recognize here we go again, Laura doing her part! Laura doing her part is a beautiful thing to see, but Selle Virtucio doesnt want to be a one-trick pony. She wants to find new sorts of parts that she can inhabit as beautifully and convincingly. And now were circling back to the question about the dancer as a work of art: because, if the dancer has an inherent and recognizable force to offer the choreographer, that is always in tension with an individual’s need to grow beyond what one is now. How does a dancer manage to changeand do it without becoming lost in a haze of self-absorption?

To resolve this Zenos paradox takes Selle Virtucio a few moments, and her answer, perhaps, contains the reason she dances. I dont know what I really am out thereshe points into the empty audience at the Southernout there, in the world, in my life. Instead, I work out a lot of that personal stuff by dancing. A choreographer will ask for a certain emotion and Ill take it somewhere, and Im learning about myself and discovering things without having to put words to them. Dance is art for Selle Virtucio, but she cant bring herself into the work without learning about herself at the same time. She cites a recent rehearsal for Eddie Oroyans Brown Rocket, one of the works featured in the upcoming Momentum series. At the end of the rehearsal, I couldve cried, for realI couldve completely lost myself. It felt like, at that moment, I was about to learn something about me that I could never put words to, but that I had just livedright there in that 15 minutes [of dancing]. And now I go out to my life and try to think about it: why did that affect me so much? Dancing connects her to new parts of herselfin that moment when the acting, the pretending breaks down and something else, something real, bursts through.

But the connection works both ways, and Selle Virtucio wants to work on the back side of the embroidery more in the next few years. In order to be able to say anything new to an audience, I need to live my life a little bit. Those feelings shes most often shared with audiencesemotional struggle, the triumph of spiritual strengthmagnificent as they are, arent the only ones Selle Virtucios capable of expressing. I need some more life experience, so I can fill myself up again, learn more about myself that I can bring to the stage. You start to feel dry after a while; you dont want to keep saying the same things over and over.

Her solo certainly shows a different woman: someone learning, trying, climbing past the defeats and victories of early adulthood, and on to the shades of gray and the wider view that come next. Her moments of struggle and ascension, here in this new work, have all their familiar power, but the ending promises to give us something new: a woman who can feel deeply, but look at her own feeling (and even laugh at it) at the same time.

All dancers have their own stories, which are similarly enacted on stage. Watch closely as the five other McKnight soloists take the stage for SOLO: who are they? where are they going? how do they find themselves in the dance? and how does their art work?

What: SOLO: each of the McKnight dance fellows for 2006-2007 debut solo performances choreographed expressly for them

Where: The Southern Theater, Minneapolis, MN

When: July 11-13; Friday & Saturday at 8 pm (post-show discussion on Saturday, July 12); Sunday matinee at 2 pm

Tickets: $24

What: Brown Rocket choreographed by Eddie Oroyan who performs with Laura Selle Virtucio; part of this year’s Momentum series of new dance works

Where: Southern Theater, Minneapolis, MN

When: July 24-26

Tickets: $18

About the writer: Lightsey Darst writes on dance for Mpls/St Paul magazine and is also a poet and editor of mnartists.orgs What Light: This Weeks Poem publication project.