Dance Review: Slightly Ajar

What will you see? Who will control what you see? Miriam Colvin tackles tough issues of media and mediation in Slightly Ajar. The show ran through December 21 at Patricks Cabaret, 3010 Minnehaha Avenue South, Minneapolis.

“We guarantee that the theater entrance will be unlocked when you arrive. We cannot promise that you will be able to open every door,” reads the advertisement for Miriam Colvin’s Slightly Ajar. And so the show begins, before the show begins, as you walk up to Patrick’s Cabaret on Minnehaha Avenue and encounter three locked doors before the promised open theater entrance. The advertisement also tells us, “You may not experience the same event as the person next to you.” Well now, this is always true, you think to yourself; of course what I see is formed in part by myself, and therefore differs from what the person next to me sees. Colvin really means it, though, so much so that you won’t be able to stop asking questions about what you did and didn’t see, and who showed it to you, for the continuation of your evening.

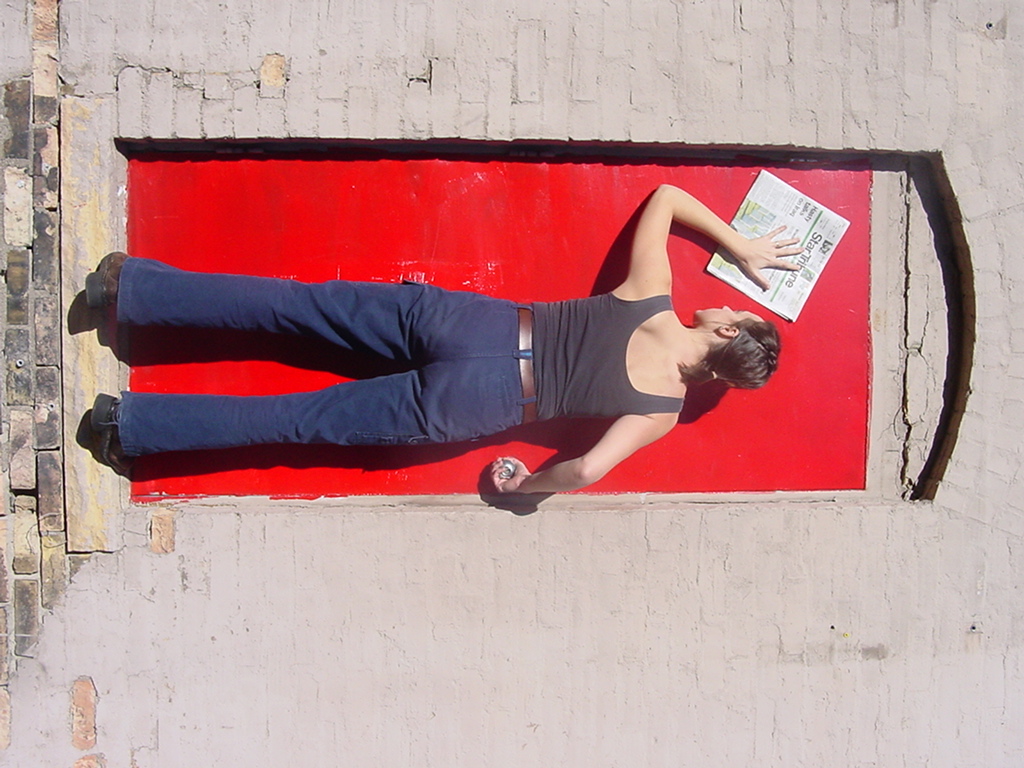

Slightly Ajar is a performance in four parts that combines the work of seven dancers, four visual artists, a musician, videographer, and lighting designer, and three guides. What kind of dance performance do you need a guide for?, you may ask. Well, the kind that goes outside, upstairs, around corners, and through doors. We, as audience members, would be helpless without them at this show, and we trust them implicitly. With our trust they also have power: the power to tell us what to do, to decide what we do and do not see, and to tell us what we should be thinking about what we are seeing. As such, the guides are an integral part of this performance, and an integral part of Colvin’s overall theme relating to the media and how it is mediated to us.

The audience is split into groups, and each group gets their guide. Ours is Dannell Dever Shu, and in a clever move to make control feel like agency, she tells us that when she rattles her shaker, we are free to move, and when she stops, we should probably stop too. She rattles and we follow her outside and through a door (that was locked a minute ago) upstairs. She stops her shaker and we huddle in a corner, and catch a few glimpses of movement at the other end of the hall. Some of us can see rather well, some hardly at all. Even if we are lucky or assertive enough to have a clear view of the hall our interpretation of the “event” taking place (a dance in another room) is mediated by another dancer, who describes to us what we cannot fully see.

Traveling through the upstairs, Shu gives us choices of things to look at, and then leads us downstairs where we see another group standing up and walking away from a video screen. We are told to take a seat, any seat, but only one seat. On the screen is the upstairs, and we realize that our recent foray was being watched by a different group. Again Shu gives us choices: we can watch the screen, or look at the papier mache sculpture and poem in the corner which she highly recommends, or we could also look at the red flowers in the window. She says red flowers are always a good thing. She offers us candy canes. We can choose between red or blue. She rattles the shaker again and tells us to walk to the lobby. She tells us to walk a certain way and demonstrates with slow exaggerated steps. She smiles and seems to be enjoying herself, so we follow her lead.

In the lobby we watch interactions play out between three dancers. Miriam Colvin is one of the dancers, and she was upstairs earlier with us. I wonder who is dancing upstairs now, and how this changes the experience of the group there now. Do they know they’re being watched on videotape? Our guide and the dancers ask Colvin questions. As she measures space on the floor slowly hand to hand, someone asks “How many?” and she says “I can’t count.” Someone asks, “So you’re saying girls are bad at math?” and she replies “yes.” Our guide then turns to us and gives us smiling facts on how this is not true, girls actually excel at math and science. She provides us with facts, and we believe her.

Shu then leads us to the theater, where we are told to take a seat, as long as it doesn’t say “reserved.” I am reunited with my friend, who has seen a completely different show up until this point. We ask questions:

“Did you get candy canes?”

“No. Why did you?”

“Who was talking to your group in the lobby, and what about?”

“I think her name was Gabriela. She was talking about baby names.”

We are guideless for the remainder of the performance, but we don’t need them anymore; after all, this is a normal dance performance now. We’re sitting in rows and watching, and we can see everything (for the most part). The dancers carry the theme of mediation through as they describe each other’s movments (or their interpretations of them) and as they occupy windows, doors, and stairs — those interstitial places that mediate between inside and out, and up and down.

I’ve seen multimedia and multigenre performances before, I’ve seen imaginative uses of space, and I’ve seen art that asks tough questions, but Slightly Ajar strikes me as one of the most innovative and alive works I’ve ever encountered. So much of it seems unintentional, or even accidental at times (while loosely organized, Colvin admits the work is about “94.8% improvised”), but at the same time I can see how each piece relates to each other, and how they each relate to the world at large. It’s abstraction based solidly in reality, and it leaves you with more questions than you came with. I guarantee that you will see something different than what I describe here. I cannot promise that you will get a candy cane.