Dalek Two Fingers of Milk, and make that a stiff one.

"Dalek: Two Fingers of Milk" is the local debut of the artist Dalek, working in a mode that derives in some ways from graffiti and in other ways from comics and commercial imagery.

Hurry in: the show is up only through the end of April. It’s all at the new Ox-Op Gallery, at

1111 Washington Ave. S. (behind Grumpy’s Bar in Minneapolis). Hours are 4-8 pm, Tuesday through Saturday, or by appointment. Call 612.259.0085 for upcoming shows.

I worry about the ozone hole but what really scares me are the toxic levels of kitsch showing up in the milk and cookies of our children. Drip-fed massive infusions of sweetness, pictures of Barney all over their pajamas, they will toddle through the rest of their lives in clouds of potpourri and baby powder, bidding up Beanie Babies on eBay, buying any figurine with big wet eyes, sippy cups of pop forever full to overflowing.

Mickey Mouse is the world’s most beloved rodent because he never leaves droppings but nevertheless spreads the virus of happiness everywhere he goes. He lights up the faces of millions of children who, left to their own devices, would otherwise be miserable and cranky forever. He is asexual, a creature entirely without menace, the very embodiment of American optimism–cheerful, plucky, game for whatever comes his way. It’s time to take the little bastard down a notch.

An artist with the graffiti tag of Dalek has risen to the task with the savage, detached glee of a cat who likes to toy with mice before biting their heads off. “Two Fingers of Milk,” a show of Dalek’s work, will be up for a few more days (through April 30) at Ox-Op, a curious little gallery situated in the dangling appendix of the building behind Grumpy’s Bar, a location as off-the-wall as the artists of comic subversion that the gallery represents.

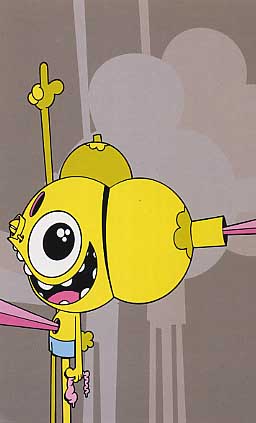

Dalek, whose legal name is James Marshall, worked out his characters, his id-Mickeys, on the grimy brick walls of Chicago and Cincinnati. Further evolved in the work at Ox-Op (mostly acrylic drawings on paper) the figures are set in an infinite white vacuity of space, and sometimes placed far off to one corner of an otherwise blank sheet to emphasize the emptiness they inhabit. Mutated from the adorable archetype into beings that Dalek affectionately calls “space monkeys,” the name is not nearly sinister enough for personages this psychotic. His Mickeys are utterly demented. Every sentimentally beloved detail is expropriated, wracked, torqued, and wrenched around to a lunatic degree. The innocuous three-fingered hands, thumbs, index fingers are now contorted into spreadfingered, downpointing gang signals, or snapped fascist salutes, or upraised like John Travolta’s hand in Saturday Night Fever. In some of the drawings, Mickey’s stick-legs are plunged into hilarious 3-toed boots, way oversized, like kids’ rubber galoshes.

The heads atop these Mickey Morphs can trouble your dreams. Their features are as formalized as those of icons of the Orthodox church. Always presented from the same angle, the head and ears are like a cluster of three soap bubbles, or the earliest stage of embryonic cell division, the blastula. On a few, the ears morph and bulge into large pneumatic breasts with the suggestion of flowery aureoles around the nipples. Some of the heads are abstracted with features blank as the drilled-out holes of bowling balls, but most have the aspect of a cyborg fitted with replacement parts for its original organs– “makeovers” with 90 percent of their heads now comprised of bizarre prosthetics, one eye socket empty, a rabid pink tongue behind a set of can-opener teeth, and inexplicable warts of hardware for a nose. Even the delineation of the lunatic gleam in the creature’s one good eye is crazier than the usual cartoonist’s device of the reflected image of a rectangular window—it’s a reflection of the creature itself. No matter how scabrous the scenes of havoc it’s involved in–standing disemboweled with a length of sausagelike intestine in its hand, radiating or impaled by (hard to say which) Dunkin’ Donut-pink laser rays, or enduring the most unspeakable chemical green farts and spillages escaping from its body–the creature always wears the same, fixed, maniacal grin.

Employing the universal shorthand of cartooning–arcs of circles, straight lines, simple shapes, “excitement” marks, speech balloons (which are always left blank, some of them inked in completely with black) Dalek is ruthless. Turning every sugared detail of Mickey Mouse against itself, he has devised a mordantly funny hieroglyphics for deriding America’s inane, kitsch-addled fantasies of innocence and power. Depicting the horrors seeping into our psyches, Dalek has the makings of a Goya for our times.