Cupboard Full of Hate: That Clutching Sensation

Lightsey Darst reviews the marvelous A Cupboard Full of Hate by Off-Leash Area in Our Garage. Call 612-724-7372 to reserve. Oct 8-9.

Off-Leash Area (Paul Herwig and Jennifer Ilse)—I’ve come to recognize this after seeing several of their productions—always brings you to a moment when, without knowing you were going to, you suddenly feel weepy. It’s Yeats’s “Innisfree” effect: you’re reading along quietly, and then you’re choked up, and you can’t point to what word did it, but now you can barely finish reading the poem—“in the deep heart’s core”. I once heard someone else give a name for it, which I can’t remember—the plunge or lunge or lurk or lunker; I call it the clutch.

How does Off-Leash Area manage to always create this effect which is so rare in the world? To begin with, they work with big themes: love and death, madness, art and life, imagination and reality. Politics and cultural theory, though applicable, are not the subject. Although the mind is engaged by Off-Leash Area’s invention, the heart is the primary field of action. Second, Off-Leash Area goes bravely and continually too far, always (like Tchaikovsky) giving the crank another turn. They do not touch on things; they dive.

I’m not saying that the clutch is an essential element of art. Intellectually engaging and politically motivating artworks abound. There’s even something kitschy about the clutch, something Reader’s Digest. The clutch can be confused with the feeling you get when you pick up an old stuffed animal, but the true art clutch is something different, unhinged, chaotic, a sudden pane of glass giving onto the heart’s desperate building. Personally, I love the clutch, which is why I will be reading Yeats, listening to Tchaikovsky, and going to Off-Leash Area productions for as long as I can.

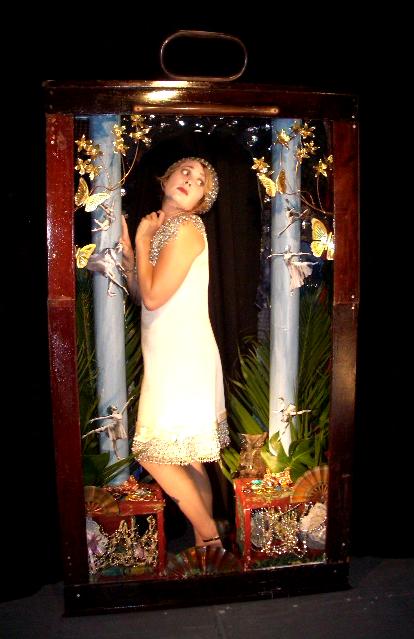

“A Cupboard Full of Hate,” Off-Leash Area’s latest production, is a clever, bitterly funny little show about a hateful man (played by Herwig) living in a tiny room somewhere in Paris. The hateful man, locked into his own obsessive routines (which include keeping canned vegetables in line), gets an eviction notice, which forces change into his life. His mind and heart appear on stage as a butler and a silent-film starlet who live in intricate, Joseph-Cornell-like boxes; they work together to bring another element into the locked room, a ghostly little girl who finally frees the reluctant man from his prison. The players are marvelous. Heather Bunch plays the landlady, screwing up her face like a woman with lemon juice for blood; Katie Kaufmann’s heart/starlet swoons and pirouettes. The little girl (I saw Isabel Rousmaniere; Sophia Ray Breitag plays other nights), serious and fragile, holds the show in her hands. Clint Jeffrey (as the mind/butler) looks mental, his eyes going curiously from side to side. Herwig’s hateful man, though manic, gross, and cranky, doesn’t seem hateful. Rather, he’s familiar—the wounded child, the misanthrope, that most of us keep in some locked cupboard inside.

While you’re laughing at visual tricks, hideous props, and funny lines in the spare French-English script, “Cupboard” sneaks up on you with its clutches—details of the intricate set, moments of dramatic action, and evocative images.

While the man sleeps, his mind/butler brings him a red flower in a specimen jar, a skull, and a stuffed bear, one after the other. The man dreams of death, beauty, a lost child, produced from the still-living, still-unhateful corners of his mind. The back wall opens and we see the girl; wicked white branches like skeletal arms hold her back.

The man, receiving his eviction notice, finds a suitcase with the word “valise” written on the side in Magritte-like script. It’s not a valise, for it contains nothing but solitude, anguish, and regret, written in chalky paint on clear plastic sheets. The man takes out these words as if they are treasured mementos, carefully placing dust, dust, and time on his now-empty cupboard shelves. White-gloved hands reach through the back of the cupboard with dried roses. Every life has a romance, even a hidden life.

The heart lives in a shadow box full of tinsel, gold metal flowers, and tiny ballerinas. All is a little tarnished, has been kept from the light and from human hands a little too long. The heart herself droops, half-asleep, in a sequined cloche and an ivory shift heavy with beads—the beads looking as if they’ve been stitched on slowly over many years, an encrustation, at once a tribute to the heart and an anchor against her flight.

Later, the little girl invites the man to play a chess game with her. On the board are a crown, a heart, and other symbolic figurines—everything we want, everything we cling to. The man makes a move; the girl takes all the pieces. By losing the game, he has freed himself—let go. He opens the chained door and leaves.