Culture Wars and Culture Gaps

Lauren DeLand looks back at the Culture Wars of the 1990s and, specifically, the facts and apocrypha surrounding a 1994 performance in Minneapolis by Ron Athey that galvanized the country's conservative backlash against government funding for artists.

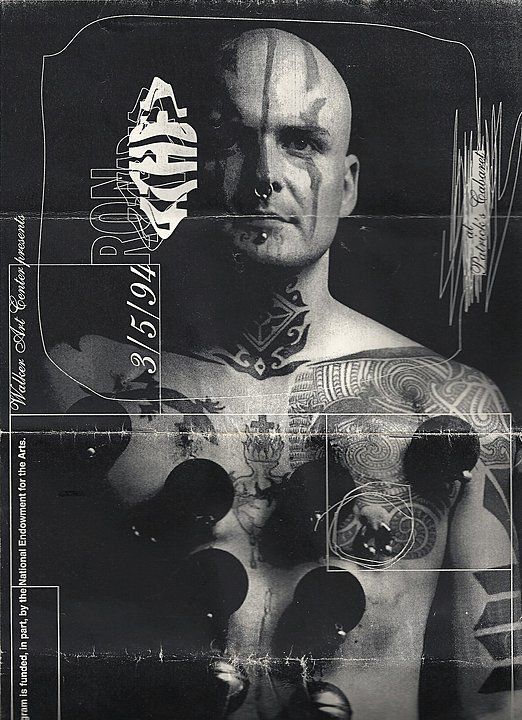

It is mid-March 2010, and I am deep in the belly of the Walker Art Center archives, settling in to watch a videotape retrieved for me by the archivist. The tape is supposed to contain footage documenting a question-and-answer session which followed a performance I have been researching for months: the notorious appearance of performance artist Ron Athey and his cast at Patrick’s Cabaret in 1994, which under Walker’s aegis featured selections from Athey’s Four Scenes in a Harsh Life (1992) and Martyrs and Saints (1994).

Yet the pale electronic pulse of the aging videotape shows me something unexpected: a flare in the dark illuminates the boyish face of a burly man as he lights a cigar. Strains of electronic lounge music herald the appearance of an enormous queen, twirling onto the stage in silvery makeup and a bouquet of balloons haloing his body. I have before me the elusive object of so many individuals’ desires: for me, it is the record of a performance about which I have endeavored to write without the benefit of having seen what I am talking about. Three weeks after the Patrick’s Cabaret event, the art critic for the Minneapolis Star Tribune, similarly innocent of any firsthand observation of the performance, nonetheless published a front-page article speculating whether Athey’s audience “could have contracted the AIDS virus” [sic] from being present at the performance, which included bloodletting.1 The ensuing firestorm that resulted from the journalist’s initial article sparked a hunt among right-wing culture warriors, from the American Family Association to the Christian Coalition, for the very document scrolling before my eyes. An article of January 26, 1995 in the conservative Washington Times chronicles the persistence of foes of the National Endowment for the Arts in their efforts to acquire a videorecording of the Minneapolis performance, alleging that the Star Tribune article did not cover “the half of [what took place].”2

In an unpublished letter to the editor of the Star Tribune of March 30, one of the two men upon whom the journalist relied for her account of the Athey performance insists that the audience would have had to “trample through blood products of the HIV infected performers” [sic] in the event of their having to evacuate the theater; moreover, he claims, the Walker was deliberately withholding from the press a videotape documenting these events.3 The truth about the Walker’s recklessness, he promises, would be made clear with the video’s release.

The tape playing before me, however, offers no such damning evidence. I watch Athey’s co-performer, Divinity Fudge, shimmy as Athey drives the tip of the cigar into the balloons encircling his body. I see him shiver under the small blade Athey draws across his back, creating new incisions in a landscape of raised, ritually-inscribed scars; two attendants gently cover the shallow cuts with shop towels and clip the resulting prints on a clothesline to travel slowly over the audience. I listen to a dismal recitation of Athey’s struggles with drug addiction and suicidal depression as he studs his arm with quivering hypodermic needles. I fidget through a long scene in which the two red-robed attendants weave a crown of willowy surgical needles into Athey’s scalp. Then an imperious Divinity Fudge appears, dressed in white, and anoints Athey’s head with water, the blood running in rusty washes down his face. The strains of organ music signal Athey’s transformation into a tent revival preacher; after delivering a booming sermon on the multivalent iterations of the word “hallelujah,” he officiates an unconventional wedding ceremony in which the pair emerges cocoon-like from white swaddling to reveal their bodies, dripping with wedding bells that dangle from their pierced torsos. As the newlyweds begin to move and the bells to ring, the four performers converge on stage in a flurry of dancing, drumming, and ecstatic howling until the house lights go down, leaving only the sound of panting in the dark.

The video supplies nothing to support the hyperbolic claims about fleeing and fainted audience members published in the Star Tribune and in subsequent, derivative accounts of the performance. Nor does the tape provide me with the conclusive evidence required to debunk them. Periods of total darkness punctuate the recording, as the performers transition from one scene to the next; there is no way to determine whether the rustling in the dark comes from departing persons or performers taking their places.

The facts which remain as true today as they were in 1994 are these: the Star Tribune published an article which was, as the author herself insisted, not a review of Athey’s performance; rather, the sole purpose of the piece was to allege a threat of HIV transmission that was both biologically impossible and, as she was obliged to admit in the same article, already debunked by local health officials. This phobic fantasy would nonetheless reach an audience that vastly exceeded the 100-odd people who actually witnessed the performance. The story spread rapidly from the WCCO to the Washington Post to Newsweek, and through the sensationalist mouthpieces of Rush Limbaugh and Pat Robertson. Ready and waiting were a phalanx of conservative Christian watchdog organizations who seized gleefully upon the $150 figure that the Walker had allotted from an NEA general operating grant to fund the performance. Well-organized from their battles over the indirect allocation of NEA funds to support exhibitions of the work of Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano four years earlier, representatives of the American Family Association, the Christian Coalition, the Catholic Anti-Defamation League bombarded Congress with mailings identifying Athey as the latest artist to peddle sacrilege and obscenity on the public dole.

Athey appeared in effigy on the floor of Congress in the form of a life-sized poster, as senators and representatives from both pro- and anti-NEA factions gave statements based on the distorted account of the performance purveyed by the Star Tribune and its copyists in the mass media. These precisely timed histrionics resulted in a compromise bill stripping $3.4 million from the NEA’s budget for 1995. However, the agency itself would shortly prove its own worst censor. In November of 1994, the NEA eliminated forever its operating system allowing local, nonprofit arts organizations to fund individual artists with federal grants. If the NEA’s spare support of certain individual artists functioned as an affirmation of our collective investment in fostering a living arts culture in America, the second, turgid act of the American Culture Wars of the 1990s disavowed it.

The response from arts and cultural institutions nationwide was swift, resounding, and virtually untraceable: as the consequences for producing and exhibiting risky work became clear, most institutions opted quietly to avoid this risk entirely. That it is extremely difficult to support a statement like this in a positivist sense reveals the truly obliterating effects of censorship: How can one comment on what is not seen, exhibited, or created in the first place?

Even so, the history of the late-20th century Culture Wars is one of constitutive ellipses that shape our contemporary arts landscape. The Walker’s hosting of performances by Karen Finley in 1990 and Ron Athey in 1994 established both artists as objects of congressional ire, and Minneapolis as a hotbed of the cultural controversies that raged over the 90s. Yet few artists, local or otherwise, are aware of this history. Athey and Finley both were for decades effectively frozen out of a system of American arts institutions spooked by the threat of right-wing bogeys, and their respective bodies of work remain virtually inaccessible to younger generations of artists struggling to articulate the same issues their predecessors addressed years before. The substantial challenge posed to all those endeavoring to write the history of the American Culture Wars is to make sense of these gaps — to give shape, retroactively, to our culture that never was.

Related event information: Ron Athey speaks at the Walker Art Center on March 26, 2015, kicking off Culture Wars: Then & Now, a weekend of events, including a symposium and performance cabaret, copresented with the University of Minnesota and Patrick’s Cabaret. Read a new Artist Op-Ed by Ron Athey, “Polemic of Blood,” on walkerart.org. Find John Killacky’s thoughts on the event in his 2014 essay, “Blood Sacrifice.”