Contingent World: Clarence Morgan at Thomas Barry Fine Arts

Ken Bloom's take on Clarence Morgan's recent show ("New Paintngs") at Thomas Barry Fine Arts in Minneapolis opens vistas that can transform the viewer's experience of the work.

Exhibition space influences our perception of art; if the distribution of works is dense or spare, or if the room is close or open, bright or dark, experience will change. For Clarence Morgan’s work at Thomas Barry Fine Arts, the lotus-toned walls and monastic atmosphere helped to fully focus the frame at each generously spaced square (or nearly square) black and white painting.

Choosing a square is consequential; the square is a powerful abstraction. It imbues the painter’s ground with an iconic language which makes the material dimension meaningful. In the past, the raw physicality of the object itself has been a key identifier of Clarence Morgan’s color field paintings, whereby sculpted paint provided a layer of meaning as its own textural landscape. The breadth of Morgan’s gestures were embedded in the surface, reaching out over a horizon that was well off the edge of the canvas.

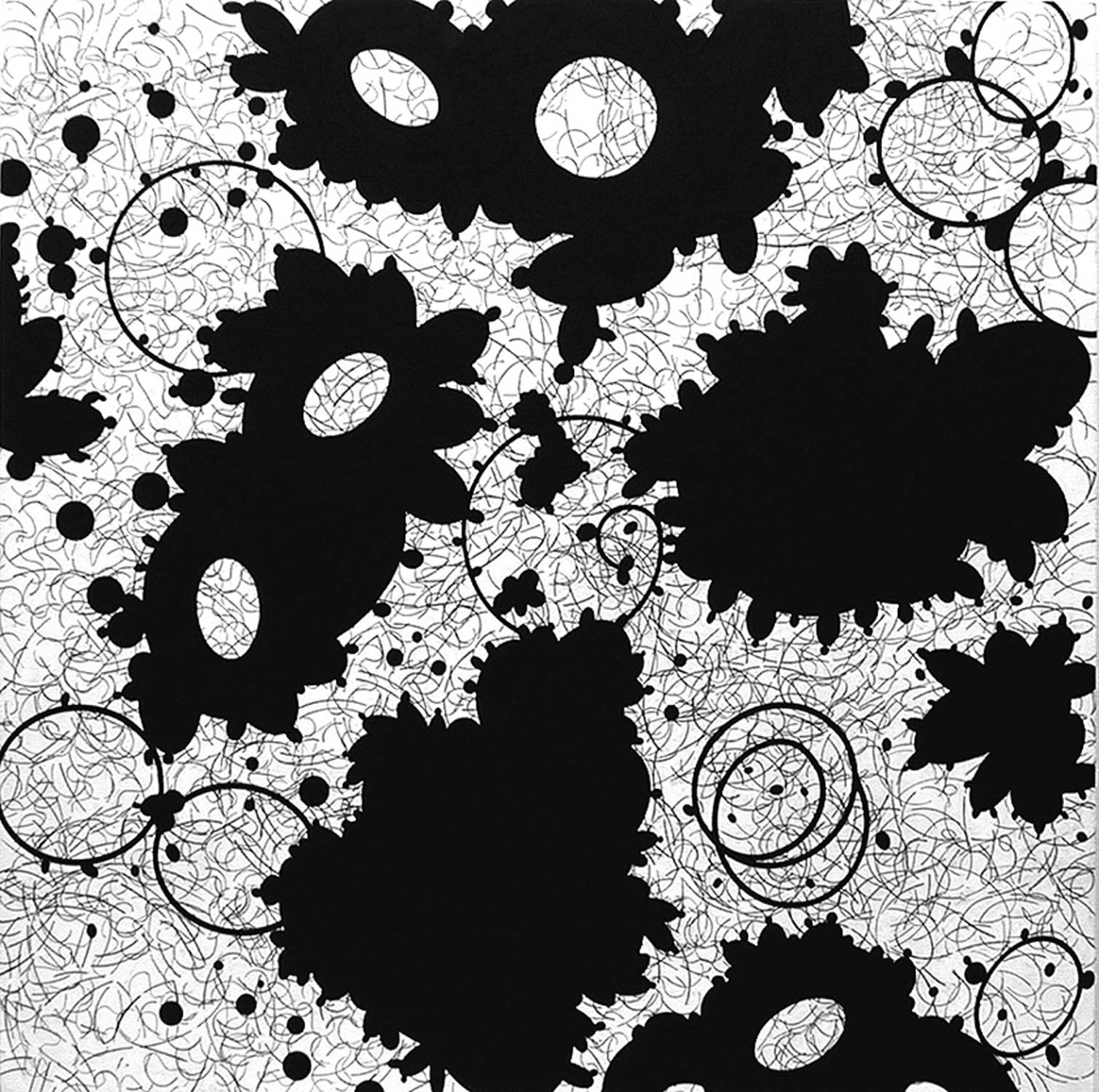

The recent work in this exhibition retains that past work’s sense of artifact, as it is both unframed and within handling scale. Otherwise the work significantly departs from Morgan’s impasto carnality in that the surface of the new paintings feel nearly transparent, flat and surgically pristine. Each work hangs in solitude, its objecthood further reinforced by Thomas Barry’s minimalist presentation.

The purity of these non-representational forms, in spare atmospheres, excites the mind to narrate, to attribute meaning. Because, in this new work, Morgan’s pictorial field is focused inward, his pictorial forms may be construed as cosmological incidents. They are pre-linguistic. They evoke feelings, tensions, teases, and terror. Morgan, starting from paintings with tangible relief, has traversed a spiritual journey from earth to consciousness. Morgan’s transformative vision is yet somehow antic and dispassionate. Each work reveals, as if through a portal, a bird’s-eye glimpse into a numinous, quickly evolving rivalrous world.

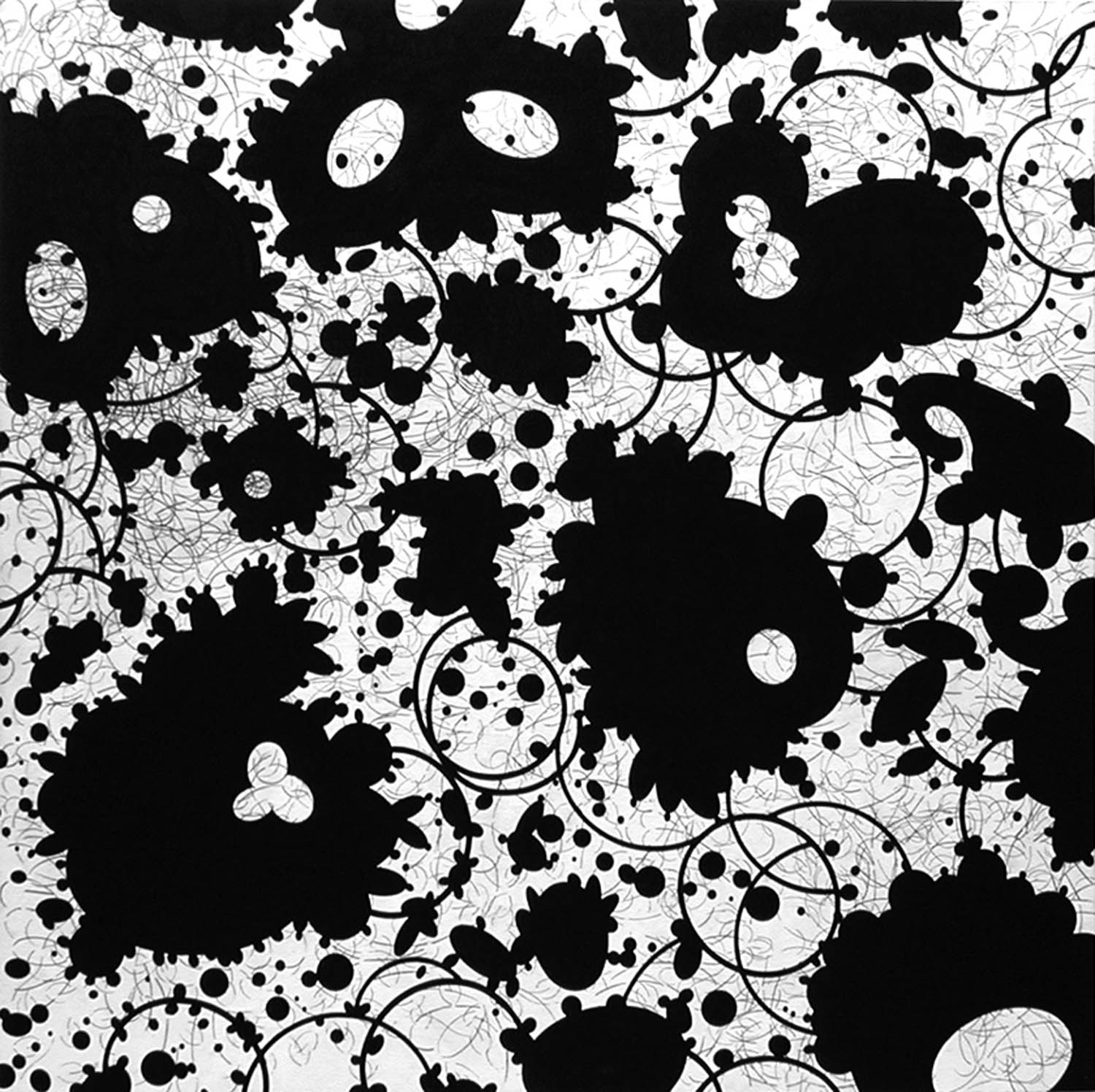

Generally, four layers dominate in most of the works. The forms here may, in fact, be codified, though Morgan offers no legend. One may assume their ground to be an activated field of some undifferentiated force, not neutral space, spread across by a layer of dense graphite sketchings, above which are black outline circles, overlaid once more by dominant solid black polypoidal forms. In a culminating triptych of 12-inch works there is fifth layer of newly activated forms that are the mirror opposite of the opaque black colonial forms. These white forms are full-bodied rivals, opaque as black in their blank swarming whiteness, obscuring all matter in space beneath them.

In trying to decipher how such forms and graphical systems might suggest meaning, one can turn to precedents such as Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, a quirky book published in 1884 by Cleric Edwin Abbott. It is Victorian-era mathematical theory turned fairy tale and social model, making allusions to the fourth dimension by way of a two-dimensioned Flatlander’s dream of a hardly imaginable third dimension. Each of Morgan’s graphical layers could represent autonomous populations that exist as Flatlanders, with each superseding layer aware only of itself and the layer(s) below yet painfully unaware of any further dimensions. In Morgan’s drilling vision we are able to look into and past each of four parallel flat worlds inhabited by vastly different social forms. As viewers, we complete the ultimate pattern and become the uppermost population. Then perhaps, beyond ourselves, were a godlike world present and invisible above ours, we might too be under observation, with all our smallness revealed.

What is the overarching syntax that relates Morgan’s work to itself and to the art in its environment? On the basis of correspondences both graphical and sociological (yes, there is a world outside the gallery). One may turn to the finely tuned mix of social comment and visual authority of Kara Walker.

Walker is well known for silhouette depictions of an absurdist antebellum world wherein relationships of the charged figurative forms suggest Bacchanalian dynamics tinged with the power imbalance of racialism, dominance, submission. Walker’s vision is permeated by parody which takes the guise of pictorial detachment; this exaggerates the power of suggestion. Though her depicted forms are figurative, they are mute, opaque, and typical devices, activated by their theatricality and elegant portrayal of human gesture without bodily detail. The graphical forms confer their irony by trading on stereotype– they address the ubiquity of meaning confirmed through prototypical forms and symbols.

The correspondences between Walker and Morgan are not in what the forms appear to be but in how they function. In the Morganian vision a silhouetted organic shape suggesting something as figurative as a breast with nipples, bivalve colonies, or cancerous tumors delivers a sense of farce and supersession much like that found in Walker’s figures. One could infer that the black budding pregnant encroaching figurations that comprise the uppermost layer of most of the paintings refer to a dream of white and black social interplay. Within the realm of meaning created by a typology of form, by black and white seriality, and by irony, Morgan meets Walker — particularly in the culminating triptych of the exhibition (that includes the piece, Critical Orthodoxy ) wherein Morgan sets black and white forms on the path to confrontation. As with Walker, the black figures ultimately prevail.

The painter provides us an uninterrupted surrogate view of potential catastrophe, otherwise outside our notice, in Lilliputian worlds. Since Morgan has originated no reference to establish scale for the fields of forms and dynamic systems depicted in these paintings, one could as easily imagine a stellar world, or an alien landscape that we would marvel from a low flying aircraft. Certainly dreams are made of such overhead visions. But if the scale is infinitesimal, which it could be, we see uncontrolled budding biomorphic shapes, as if replicating amoeba were in a race for consuming all resources in a sightless world.

At the scale of the bottom layer is a population of forms depicted as hundreds of parallel hatch-lines forming a broad but decentralized community of cross-hatching genetic pairs, symbolizing resemblances and correspondences of minute individuality, with none that predominate. Though rhetorical devices, they are chaotic and vulnerable in their broadly distributed but unfocused discursive order. Above them are revolving circles of action or influence that may intend to roil aimlessly within their own spheres of influence. The dénouement is in the overlay of the ever-broadening scope of colonial forms that will obliterate all that lies below.

Whether our eyes are peering into a world small or great, a symbolic struggle for survival of species is taking place. It is both mythic and real as war, eternal and amoral. We are transported from pure formal visual structure through fantasy, physics, identity politics, and genetics by way of mutating distributions of forms across the pictorial field; by way of otherwise uncoded relationships of pure form and texture, into a contingent world of competing forces and indeterminate futures.