Consumed by the Hungry Air: “Solo” at the Southern

Lightsey Darst writes about what it is that dancers do, inspired by "Solo," the recent McKnight showcase of dancers' work at the Southern Theater. See also the collection on mnartists.org based on this work.

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

—W. B. Yeats

An evening of six solos commissioned for and performed by the six McKnight Fellows in dance from 2004 and 2005, “Solo” offers a chance to consider the above question (admittedly in a literal sense). What exactly is it that dancers do? In critical writing their accomplishments often show up as footnotes to a discussion of the choreography; alternately (and especially in ballet criticism), critics treat them as if they were thoroughbred racehorses, whose achievements are due to genetics and whose faults are due to fear or foolishness. Clearly we need to make new efforts to talk and think about dancers and dancing. What are the talents, the achievements, the difficulties involved in being a dancer? With little traditional “dancing”—no pointe shoes, no pirouettes, few sustained sequences of steps—“Solo” offers complex and interesting answers to these questions.

Peggy Seipp-Roy (dancing “Evolution,” choreographed by Stéphane André, Wynn Fricke, and Uri Sands) demonstrates that certain dancers have certain qualities, and it’s up to directors or choreographers to make the most of those qualities. Seipp-Roy, a long-limbed, graceful ballet dancer (just retiring from James Sewell Ballet, alas), doesn’t connect with the audience; when she’s merely being human, her stage presence, despite her size, is small. She’s not particularly a mover, either—not that she’s in any way deficient, but watching her execute steps isn’t a tremendous pleasure. What Seipp-Roy does (and does extraordinarily well) is become other. One moment she’s zig-zagging across stage and you’re dozing, but the next moment she’s writhing on the floor in a pool of light upstage like some just-discovered sea creature, and you’re wondering, do I really know her? Is that the same woman? In so far as the choreography fits her gifts, Seipp-Roy incandesces; she surpasses most other dancers in her ability to take an image. The conclusion of “Evolution,” in which Seipp-Roy winds herself back up in a long sheet of tulle, taking for wings what originally suffocated her as a cocoon, would not work on a lot of dancers, but Seipp-Roy carries off its epiphany with otherworldly grace.

Mariusz Olszewski, trained in ballroom and jazz (visible locally in Beyond Ballroom Dance Company), proves that dancers are athletes and entertainers. With his knife-edge turns and rapid hip swivels, Olszewski also fits a conventional definition: a dancer is one who moves to music. There’s no doubt that Olszewski can dance (can move, can hit the beat), but the miscellaneous “Tango Emigranta” created for him by Tomas Howlin and Jean-Marc Genereux suggests one of the difficulties of being a dancer: you are not responsible for the material you perform, which, if mediocre, will leave you no room to prove that you are an artist as well as a skilled athlete.

Julia Tehven reminds us that dancers are beauties in body and face, people we love to look at. This beauty often isn’t the conventional type; instead, dance has its own types. Tehven is recognizable as the prototypical ballerina: waif-thin body, prominent collarbones, the reverse cleavage of ribs showing in her chest’s vee, large sunken eyes, strong cheekbones, and that famished, soulful look, which serves her well in “Mrs. Hamlet,” John Kelly’s evocation of Ophelia’s last drowning moments. Lucky Tehven has scored some of the best choreography of the night—not that she’s not equal to her opportunity. Tehven, dancing, transcends the step; like a good dancer, she does not appear to be dancing, just being. This ability to move in character is essential in a piece like “Mrs. Hamlet,” where there is not so much dancing as moving and image-making. Should we call this acting? If so, it’s a particular kind, involving empathetic intelligence rather than imitation. Tehven seems to have taken Ophelia into herself, to be Ophelia even in her resting moments, even in her articulate hands. When she finally drowns, she’s not so much acting as inwardly meditating her drowning. Tehven’s performance clarifies the relationship between choreography and dancer: if the artistry of the latter does not match the artistry of the former, something is lost. In “Mrs. Hamlet,” much is found.

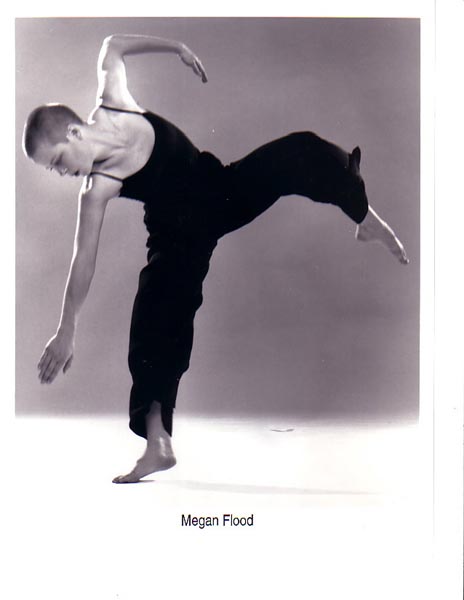

Megan Flood, dancing Dylan Skybrook’s “Sweet Megan Vicious,” has to take off her clothes, swear, seduce the audience with her eyes, and generally play against her own fairly well-known wholesome personality. What can’t you make a dancer do? To some extent flexibility defines dancers—bodily and emotional flexibility, as well as what those outside the business might call shamelessness. Flood’s flexibility extends to her ability to bear pain—she hits herself over and over in the side—and her performing genres—she dances, acts, sings, and talks. Flood’s also willing to follow the material wherever it leads. Unfortunately, in this case it leads to an unconvincing epiphany. Choreographers, like short story writers, frequently require transcendence of their characters, but even the best dancers can’t make unsupported revelations believable. And Flood is an excellent dancer. Her physical mastery shows as even her toes and fingers articulate her character’s changing mood. Good dancers know exactly what their bodies are doing. If you think this isn’t so impressive, step into any yoga class and see how difficult ordinary people find it to keep their limbs straight and their shoulders down.

Stephanie Fellner isn’t the only one of the six soloists to appear in a fabulous costume, but her get-up is especially challenging: a tuxedo shirt and jacket, cummerbund, high hat with a veil, and a flamenco skirt so bouffant that Fellner looks like a nudibranch when she rolls over. How can she possibly dance, or do anything more than parade around? Fellner’s work is made more difficult by the actions she’s required to perform—straining for a hanging carrot, shooting her own skirt, and so on, for a half-comic and wholly absurd ten minutes (choreographed by Susana di Palma and Myron Johnson). Yet Fellner somehow manages to connect with the audience through (or despite) her character. Her eyes look out at us; something in her posture, how she carries her small body, assures us that there is more inside. Call this the dancer’s act against the choreographer. Dancers are not blank canvases; more accomplished, more mature dancers are less blank still. Fellner is fascinating on stage because each time she shows up, she brings something of her own with her: a fiery, generous, yet inexhaustible energy.

Toni Pierce-Sands finished the evening with Ronald K. Brown’s “Clear as Tear Water,” a short solo in an especially vital version of the contemporary ballet/modern/African-infused style. At this point in her career (after dancing with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, among others), Pierce-Sands does not need the McKnight to prove that she is a superlative dancer. Her long arms and legs stretch out into space, her body stays free and light, her timing’s alternately syrup-lazy and cayenne-spicy; but more than this physical expertise shows up on stage. In a conversation, Pierce-Sands commented that unlike most dancers (who lose their eyes in the stage lights or fixate on faces without perceiving), she actually noticed people in the audience, their faces, clothes, where they were sitting. I could see this happening as she danced. It wasn’t that Pierce-Sands was distracted. Instead, she was doing something on stage, she was happening, living forward in that moment. Pierce-Sands compared dancers to chameleons, an unfavorable comparison because the chameleon’s change is external only. What Pierce-Sands valued more, what she tried to achieve, is bringing the dancer’s self into the work at hand. Seipp-Roy’s otherworldliness and Tehven’s immersion are two possible performance modes; Pierce-Sands shows another, rare because it requires that the dance’s work is essential to the dancer. The epiphany at the end of “Clear as Tear Water” (a slow walk to upstage, a circle of light, and then a rainfall) was real, an onstage epiphany about movement, self, and communication.

After Friday night’s performance, a standing ovation began. It was deserved. Like all artists, dancers work hard. Too often, though, we don’t perceive the evanescent artwork—their talent, their fire, their intelligence—that they give up to our eyes and the hungry air.