Complicated Grey Eyes

Sean Smuda writes on Beth Dow's show at Franklin Art Works, "Fieldwork." It's up through May 26 (along with Jay King and Mario Diaz de Leon in the video gallery).

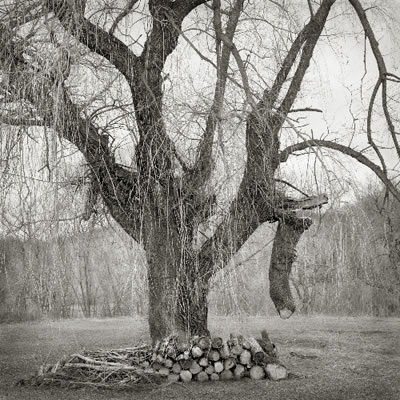

What is it we wish from fieldwork or a field of view? Beth Dow stops short of the romantic notion of artist above nature and brings an illuminated gardener’s punctum to its pruning. Despite straightforward appearances, her work teems with history and philosophy in a comforting, meditative way, like gardens of the sublime* domesticated and available for personal consultation.

Nineteen or so 16” square plots of palladium printing, with its large tonal range, show patterns not fully visible to our colored, roving eyes. Dow guides us through space, not a black and white one, but into grey hovering mists that position our field of view within them. Perhaps here can be our simple wish: to wonder at the presence of infinity and singularity.

Led Zeppelin IV was an early influence, “something ominous”, she said. And it seems this is the existential drama at the roots of her work. In its cover art a country man hunched over by a large bundle of sticks props himself up with one: a gesture of self-assertion. Like many of the gestures recorded in her landscapes, it shows interdependency between humanity and nature.

Despite the lack of human figures, signs of devastation and clearing are generally the recognizable point of the compositions. They interrupt the field and give us a way to consider our presence’s tenuous hold and its place in the larger presence of nature. Where we go for sustenance and shelter is also where we go to be buried or scattered. What we glimpse in it is something both within and beyond our control, sometimes making it usable, sometimes ominously punctuating the land.

Informed in parts by nineteenth-century photographer P. H. Emerson** and seventeenth-century gardener William Lawson***, Dow composes and shoots quickly with a hand-held medium-format camera and then crops square: an instant meditation on both the medium and its metaphysics. This forced geometry creates visual tension involving the entire frame that doesn’t allow for wandering off. The viewer’s gaze must find its way through densely detailed patterns. A glimpse at the road beneath our feet reveals specks of dirt like the cosmos; a web-fine collection of vines reveals a keyhole shape. Sometimes these only seem to go so far, but that is their domestic allure: a center weighted burning stump represents a glimpse both into the beyond and into a field clearing schedule: sublimity’s horror balanced in the squared order.

*The quality of transcendent greatness, whether physical, moral, intellectual, metaphysical or artistic. The term especially refers to a greatness with which nothing else can be compared and which is beyond all possibility of calculation, measurement or imitation. This greatness is often used when referring to nature and its vastness.

**so scientific a photographer that he thought only one point in a photograph should be in focus: “Nothing in nature has a hard outline, but everything is seen against something else, and its outlines fade gently into something else, often so subtly that you cannot quite distinguish where one ends and the other begins. In this mingled decision and indecision, this lost and found, lies all the charm and mystery of nature.”

***Lawson was a Protestant vicar whose book The Country Housewifes Garden is notable for its attention to the role of women: as cooks, lovers of fine flowers, and keepers of the herbal medicine cupboard. The books is also known for its many fine woodcuts. Gardening had become a national passion in the sixteenth century. Then, as now, it was a recreation that brought peace and contentment, providing a welcome escape from the trials of a turbulent age.