Carleton Curiosity

Susan Clayton discovered an odd little treasure in the Carleton College library: a miniature cabinet of wonders by artist and miniaturist Jody Williams--usually a book artist.

Thoughtful curation – and some serendipity – have brought artist, patron, and institution together at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota to produce Observing, Thinking, Breathing: The Nancy Gast Riss ’77 Carleton Cabinet of Wonders, a permanent installation that examines the processes inherent to an American liberal arts education. Because many who facilitated the commission, including artist Jody Williams, are alumni, the piece primarily reflects the Carleton experience.

Dedicated this past winter, the work honors Nancy Gast Riss, the first woman to graduate with distinction in economics at the college. After her death from ovarian cancer in 2002, Nancy’s brothers David and Dick Gast, also alumni, looked to Carleton as a natural place to fund a memorial to their sister. Their inquiries at the school led then-Laurence McKinley Gould Library Curator Thomas O’Sullivan to connect the family with Williams, a Minneapolis book artist and printmaker who, happily, also graduated from Carleton in the 1970s. O’Sullivan, who in February left the college to pursue other projects, knew that the artist had long been interested in the idea of constructing a “wonder cabinet” as a vehicle for biography. Realizing that Jody’s time at the college overlapped with Nancy’s, he proposed that Williams return to campus to develop her idea for installation in the library. Although the women were not acquainted as undergrads, Williams could bring a unique knowledge of the place and the time to the project and so was approved as the first Artist in Residence by Gould Library staff. “We all agreed,” said O’Sullivan, “this was an artist’s concept that had met its sponsor.”

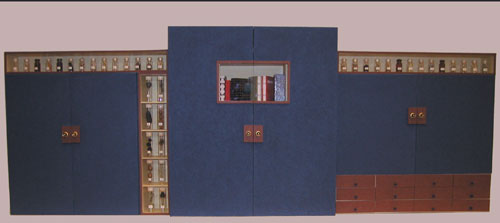

The resulting work is literally a cabinet, albeit a tabletop miniature modeled on Renaissance-age cabinets of curiosities, embryonic museums that featured the collected specimens of anything and everything that could possibly provide knowledge about the natural world and the ingenuity of man. The cabinet form, providing a means to comment on how museums and universities have historically ordered and institutionalized ways of knowing, has lately been appropriated by artists nationally and internationally. To commemorate the Sesquicentennial of the University of Minnesota’s charter in 2001, for example, installation artist Mark Dion and a group of student assistants mined the entirety of the U’s diverse collections, resulting in a provocative, chock-a-block cabinet and salon wall filled with likely as well as questionable artifacts at the Weisman Art Museum. Such artist-driven arrangements enable viewers to make new associations about meaning and material culture. Accordingly, Williams’ cabinet, which grew from extensive research on the history of the form, provides a research tool, if you will, prompting connections between the objects included and the viewer’s own experience.

Williams is the sole artisan of the piece, having applied her knowledge of book-making techniques and materials to form the cabinet architecture and to furnish it with functioning doors, drawers, and shelves. She collected or reproduced specimens from the physical environment of the Carleton campus, adding her own memorabilia as well as contributions from the Gast-Riss family. The finished work has the apparent logic of a Hold Everything catalogue, its contents arranged in an orderly and visually appealing way, decidedly on-kilter. The three-part construction is packed with small bottles and vials, some visible even when the cabinet doors are closed. Contained within are such things as seeds from campus plantings, water from the drinking fountains, fluid used to clean Nancy’s I.V. tubing. Tools, maps, photos, furniture and the requisite paperwork of academia are represented in miniature throughout. Reading left to right, a section labeled “Observing,” holding small binoculars and a magnifying glass, suggests the processes of research. “Thinking,” largest and central, includes a small desk bearing a typewriter and a bottle of Jack Daniels. Placement of a bookshelf “within reach” of the desk prompts the viewer to imagine being at work, consulting the volumes on Gould, Gast Riss, and the town of Northfield, tiny artist’s books that are more typical of Williams’ usual scale. The artist’s personal touchstones live in this section. Gast Riss is most present in “Breathing,” with its references to her time at Carleton and to her family, work, and illness.

Artifacts are numbered. Following the precedent of the early collectors, Williams provides a detailed inventory of specimens. Items recognizable at first read, from the mundane (a stapler) to the exalted (a Wellstone button,) take on layers of meaning as one scans the inventory key. In this way, the viewer becomes the seeker, observing and thinking. Williams includes objects that appeal to the viewer’s curiosity, asking that we confront our own experience of discovery, question what is saved and what is discarded, perhaps even wonder where our own college ID might be stashed. In the key, artifacts are identified, but not necessarily interpreted, allowing for the kind of endless play of speculation that constitutes collection and exhibition before rational taxonomies are established. Carleton Cabinet objects thus decoded evoke a gamut of human experience: endeavor, loss, whimsy. The stapler, it turns out, is vintage, 1974. Wellstone, of course was on Carleton’s faculty. You’re on your own with the college ID.

Jody Williams is the proprietor of Flying Paper Press and is an instructor the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) and the Minnesota Center for Book Arts. At 18” x 48” x 4”, the Carleton Cabinet is the largest work of her career. Self-described as obsessed with the small, she publishes The Diminutive Digest, “a tiny periodical devoted to tiny things,” twice a year. Since graduating from Carleton Williams has kept in touch with members of the art department over the years. She found returning to campus to research this project especially rewarding in that she was able to make new connections with her mentors, with students and with library staff, who became helpful partners. As the explorers who stocked the original wonder cabinets did, Williams drew on her experience of international work and travel while planning the Carleton piece. Currently, she is supervising the independent study projects of several MCAD students at Burren College of Art in County Clare, Ireland, where, she reports, she is “collecting specimens, since I got hooked doing the cabinet.”

Inevitably, the Cabinet includes in-jokes accessible to Carletonians past and present. Placed within a quiet seating area of the Reference Room, the piece succeeds in providing a breathing space for students at work in Gould Library. Any visitor, for that matter, who has ever been a student anywhere is invited to stop and contemplate that time of discovery, of becoming oneself. The work is for collectors as well, for anyone who has thrown a few unusual rocks into a drawer. Williams has created a piece that can be read and reread and its site affords a changeable life for the work. As is often frustrating with books that are displayed and preserved behind glass, the wish to touch and manipulate is immediately thwarted; hands-on access, however, can be arranged by contacting the library. The look of the piece changes periodically, as the curatorial staff often rearranges the configuration of the doors and drawers. After a campus-wide email reminder to shut all doors in the cold weather, for example, Curator O’Sullivan dutifully grabbed his keys and went to close the cabinet.

For further information contact the Gould Library Special Collections staff at 507.646.4260 or go to the website below.