Bhakti: Ragamala’s Sacred Connection

Dean Seal saw Ragamala's dance/text on faith at the Southern Theater. He loved it. Here's why.

A dream has been realized; a great potential has come together in the powerful matching of three great, world-class artists who have honed a piece of performance theater as spiritually moving as any religious ceremony I have witnessed. “Bhakti” takes the eerie tonalities of ancient Germany (worked by Ruth MacKenzie) and weaves it into the mystical tonalities of ancient India (with Nirmala Rajasekar). Tying them together is the interpretive movement that pours off the rich soundscape like sheets of water, in the choreography of Aparna Ramaswamy. It is one of the best things I have ever seen in 30 years of seeing shows; it is easily the best piece of interfaith conciousness-raising I have seen committed to the stage. It is sacred work, and it elevates anyone lucky enough to experience it.

Ranee Ramaswamy has always pushed her classical India Dance Troupe into uncharted territory. She has famously collaborated with a deaf actor to work American Sign Language into a choreographed work, for example. She has for this performance given the reins to her daughter Aparna, who has choreographed it in the classical style of Bharatanatyam. The work connects the eighth-century poet Andal , from India, with the eleventh-century poet/composer/mystic/doctor and critic of the Pope Hildegaard von Bingen, from Germany, and it succeeds magnificently. Aparna teamed up with Ruth MacKenzie, composer/singer who has dug deeply into ancient Finnish stuff; and with Nirmala Rajasekar, who has done the same for Carnatic vocalization from the South of India.

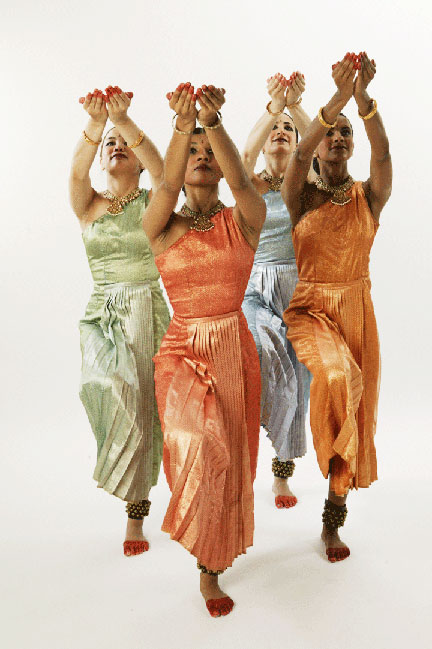

The result is a rich tapestry of deep color, soaring poetry, dramatic staging, classical and modern movement side by side; specifics of tradition shuffled seamlessly next to modern, arhythmic asymmetrical swells of soft, free movement. Vocalists trade off going from India to Germany and back; then suddenly it is Indian lyrics in German tonalities, or German harmonies soaring over strictly Indian melodies. Sometimes it is just Ruth singing and just Aparna moving to it, and sometimes it is Ranee coming in exactly in sync with Aparna while the chorus of dancers circles about behind. Sometimes it is just the drummer and flute player soaring into the stratosphere of flawless tones and beats. You may see six of the dancers softly opening up to the heavens as they come to life, or see the sprites running in and out; or maybe Aparna comes around the corner ready to tear off a featured piece of power. This is a fully integrated piece of art, a fully realized work of beauty, a categorical success in making resonant the deep richness of spiritual life, connecting us to the abundance that is a spiritual life well-lived.

The setting is the dusky jewel called the Southern Theater. Its nineteenth-century crumbling proscenium is never so well-utilized as here, to project an image of worn but surviving human civilization. Lighting designer and artistic director Jeff Bartlett usually lines up his equipment to blow away an audience, using par cans the way Napoleon used artillery (that’s a compliment). But here he shows his ability to shade, to softly crosshatch across a backdrop of fabric and brick; to spotlight a solo singer while two dancers work towards the foreground; to make murkiness attractive. He is discerning and delightful in marking sections with a stream of sand falling out of a solo special.

This is a landmark production in the history of interfaith performance, and deserves to be seen around the world. It is so much more than a dance concert. It is a groundswell of peacemaking, a deeply satisfying testament to the humanity of bare feet and naked voices. It is a rich love-note to the universe.