Beyond Likeness: Light Shed on the Body

Suzanne Szucs traveled to the North Dakota Museum of Art and saw the "Beyond Likeness" show there: four women thinking about appearance and its representation.

Light, in both its physical and metaphorical aspects, is essential to art. Light beams into the North Dakota Museum of Art in Grand Forks, illuminating the lofty galleries of this converted gymnasium. Inside, the work glows, it has room to breathe, to respond to the luminance. My visit to NDMOA comes after a long drive from the Twin Cities – I feel like I have entered an oasis.

It also happens to coincide with an event designed to recognize the museum’s director, Laurel Reuters. She is being given an honorary doctorate for her 30 plus years of service to the community, and to artists from Minnesota and the Dakotas. The galleries are bustling with wellwishers. Laurel takes time out to speak with me about the exhibition, someone is handing me cake; I am smitten by the sun glowing over the work of Anne Harris. It’s clear that here, on the banks of the Red River, art is valued.

Showing in the main galleries is Beyond Likeness, an exhibition of photographs and drawings by women who use their own bodies to explore corporeal and metaphysical space. The museum is structured with a central information desk with large galleries winging out from either side; the openness of the two competing spaces is particularly suited to the intensity of the art.

The left side is filled with the drawings of Anne Harris. I am particularly taken with this literal body of work. Harris has used her own body from which to draw studies “of gravity and inner space.” These are fleshy images, often in large formats, and work tremendously in showing the viewer the nature of the physicality of being a woman, compounded by that transparency of never really being able to objectively evaluate oneself. Harris says, “I don’t know what I look like anyway,” and her grid of dozens of small portraits featuring only her face and head are testament to this impossibility.

Women have consistently struggled with representation and in today’s world of digital manipulation, it is common for even Oprah, that paragon of “Woman-ness,” to have her images digitally slimmed. Art in itself has become about fashion, and how the female artist looks sometimes competes with the content of her art. Harris’s heavy and sagging studies challenge this societal expectation of perfection. It is relieving to find her bodies as much about a state of mind – how do I feel inside my body – than of contemporary beauty. Ironically, her bodies are closer in form to the buxom and robust women of Rubens – made during a time when ideal physical beauty was much different than today.

Yet this work is not a feminist backlash at our cultural obsession with physical perfection (how one measures that is a whole other article); rather, it records visually an obsession with the relationship of interior and exterior physicality. As a byproduct, we see images representing real physicality, comparable perhaps to the studies of John Coplans, where weight itself is representative of the human condition.

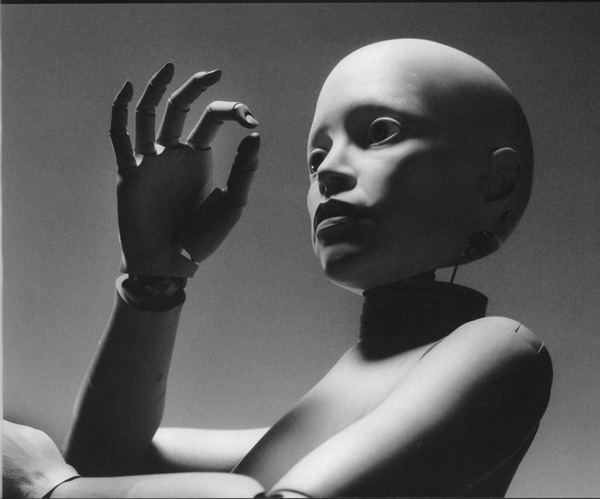

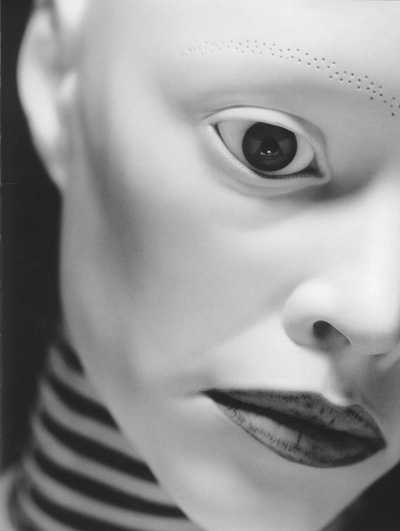

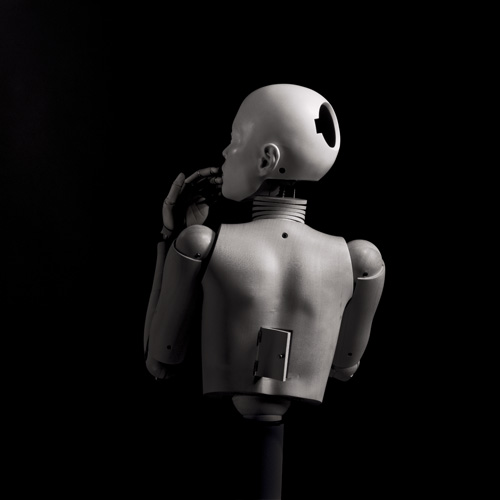

On the other end of the spectrum, Elizabeth King has created porcelain manikins that are based on her own likeness. Represented in the exhibition as photographs and video, these are uncanny pieces that question where personality begins. The videos are the real stars here – the photographs are beautifully made, and somewhat reminiscent of Hans Belmer, but they don’t represent the illusion of life. The animated works do, in the motion they capture. To imbibe the unreal with characteristics of the real fascinates us – the long history of puppetry is testament to that. Here the mimicry allows us to question the nature of self. King’s creations are meticulous and convincing; when the manikin stares us down, we are put on the defensive. It reminds me of how seldom we peer into each other’s eyes, how simple it is to overlook the intricacies of gesture in defining who we are.

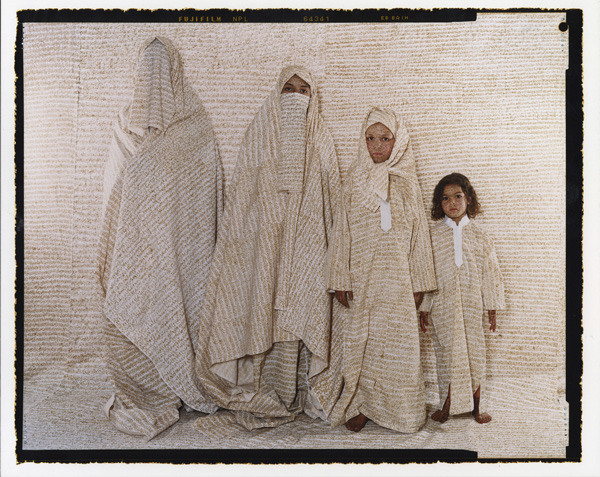

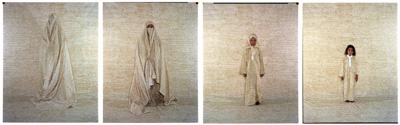

Jennifer Onofrio and Lalla Essaydi share the other main gallery. It is an interesting mingling: Onofrio’s work is dark, spare and abstract, whereas Essaydi’s large color images are busy and bright. In disrupting each other, tension is relieved for the viewer, although I believe that Essaydi’s work benefits more from the interplay.

Essaydi’s work Converging Territories catches one’s attention first. Lines of Arabic written in henna across her models and the surrounding space crowd the images. Printed in large format (approx 4’x5’ each) they are gorgeous, the language floating and pressing like earth on the airy white-shrouded bodies. I find myself wanting to know what the text means; instead, I am left with the impression of the weight of those words. They hover in my own preconceived notions about another culture and the degree to which language forms us even as images do. I drift into thinking about Sheherazade and her ability to manipulate words – the power in that gesture as a metaphor for the role of art in rethinking cultural assumptions and expectations.

Less powerful for me are Essaydi’s still lives of traditional objects used in the wedding ceremony. Again, they are beautiful images; they don’t, however, have the impact of the living models weighted by ritual, consumed and complicit in it. Here I really want some textual understanding, as the writing feels more like a visual cliché in these images.

Her visually simple work means that Onofrio had perhaps the most difficult position in the exhibition. It’s not visually seductive like Essaydi and King’s, nor psychologically gripping like Harris’s. Reuter was right to use it to break up Essaydi’s work, giving that project some breathing space, and probably strengthening it. But I’m not sure how Onofrio’s work fared in the process. Ultimately there is a mystery inherent to these images that makes them compelling – they function like reliquaries, body parts abstracted and fixed in space. Also, this is the one project that was possibly over-illuminated. I imagine that, shown all together in a darker space with more directed lighting, the simplicity of their abstraction might lift them to the level of religious icons – the flesh made real. Here I am distracted by similar work that is less abstract – Lorna Simpson in particular – and want to see these images together in their own right to experience how they ultimately interplay.

There is an obsessive quality to all this work, whether writing endless lines with henna, paring the human form into basic shapes, creating meticulous reproductions or drawing lines of shifting human form, that gives the viewer a tremendous amount to consider, with the eyes, heart and mind. Laurel Reuter has brought together a provocative exhibition that deserves to be seen by a wider audience. Which means, readers, we all need to get out of our little worlds and get ourselves to the other side of the state. The best art no longer happens in the big cities – thanks to tenacious curators like Reuter.

”Beyond Likeness” was exhibited at the NDMOA March 27-May 13. Reuter has intentions of touring that exhibition if appropriate venues can be found.