Beauty with the Charm of a Razor

Twin Cities-based painter Ruben Nusz offers a close reading of haunting new work by Belgian painter Michaël Borremans, whose paintings were on view in a recent exhibition, "The Devil's Dress", at David Zwirner in New York

Michaël Borremans is a painter.

Michaël Borremans is an aesthetic historian.

Michaël Borremans is a surrealist.

Michaël Borremans is a sorcerer.

Michaël Borremans is a painter.

Michaël Borremans – Painter

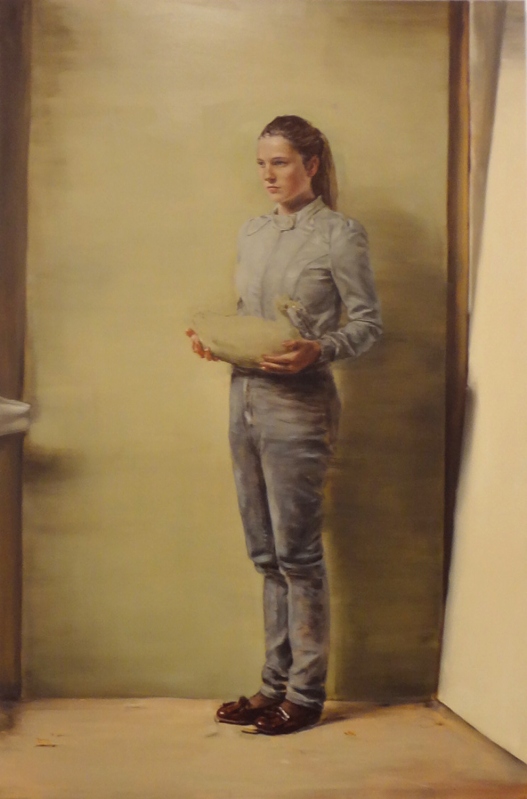

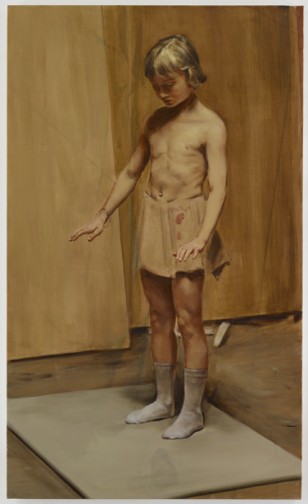

Michaël Borremans paints using a traditional figurative, humanist style, but with a twist. His subject matter, according to the David Zwirner gallery press release, consists of the “simultaneously nostalgic, darkly comical, disturbing, and grotesque.” But what attracts me most to Borremans’s work is the stillness he conveys in his paintings. Though most of his images contain the figure, one could also reasonably categorize them all as still life. Humans are objectified, not in a misogynistic way, but in order to freeze the clock, to hold on to time. A sense of desperation seethes behind the work. Borremans’s people do not stir; there’s no indication that they might ever, someday, even shiver. They are statuesque forms, unmoored from time, imbued with only echoes of life and memory. And with the blink of an eye or the turn of one’s head, the images might vanish, but the emotion they carry lingers with the viewer long afterward, as resonant as the extended vibration of a tuning fork.

Michaël Borremans – Aesthetic Historian

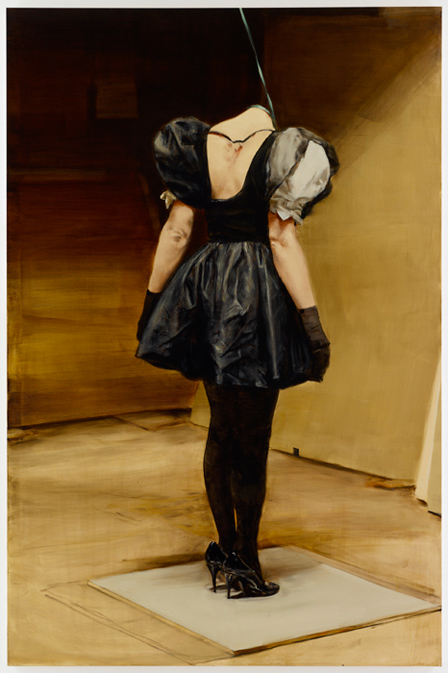

Michaël Borremans mines epochs’ worth of painting for artistic and conceptual touchstones; allusions from art history appear throughout his work. This vast assortment of references in his paintings creates an aesthetic archive of sorts, historical layers upon layers set in the midst of Borremans’s own lucid and distinct artistic vision. He alludes to Diego Velazquez (color), Edouard Manet (flat paint), Francisco de Goya (humanism), Rene Magritte (surrealist impulses), Gerhard Richter (photographic references) and Johannes Vermeer (touch, studio settings), amongst others. The Loan, in particular — with its female figure cloaked in black — calls to mind the American painter, John Singer Sargent’s well-known work, Madame X.

Like a true determinist, rather than deny his influences, Borremans embraces them, self-consciously holding them near. In the film, A Knife to the Eye, Borremans remarks: “When you make a painting, you know you are using a technique with a whole history. I think it precisely interesting that painting has a history that you carry along.”

What sets Borremans apart from his contemporaries and ties him even more closely to historical artists is his perfect grasp of human anatomy. For example, Neo Rauch was exhibiting in the adjacent space at David Zwirner gallery when I visited; Rauch’s treatment of the figure looks like undergraduate art school-level painting by comparison. Borremans completely comprehends the interplay of human bones, muscles, and skin — something one only gets from disciplined practice and extensive looking. I’ve always thought that Leonardo da Vinci was a better painter than Michelangelo for just this reason: despite Michelangelo’s uncanny sculpting abilities, da Vinci simply had a better painterly grasp of anatomy, thanks to his grave-digging past.

In a way, Borremans, too, unearths graves, disinterring past painters to smear their crushed-up bones upon the canvas for all to see.

Michaël Borremans – Surrealist

It’s no surprise that Borremans shares his Belgian origin with painter Rene Magritte. Surrealism (which was highly influential to Magritte) included the idea that an emphasis must be given “to the connotations and the overtones which ‘exist in ambiguous relationships to the visual images.'”1 Some psychoanalysts surmise that Magritte’s play with reality and illusion might be attributed to his obsession over the death of his mother,2 but that’s a profoundly reductive understanding of his work, and it denigrates Magritte’s genuine explorations of metaphysics. Rather, both Magritte and Borremans delve into the nature of our ostensible reality to better understand the nature of our non-reality — or, more specifically, our post-reality. Each artist references the incongruous inseparability of creativity and death, that an understanding of our mortality serves as the impetus for human action. Religion, science, art — all of them look to prolong our all too short-lived existence in some fashion. Further, death is nothing if not absurd — life, too. Why shouldn’t painting reflect these perennial truths?

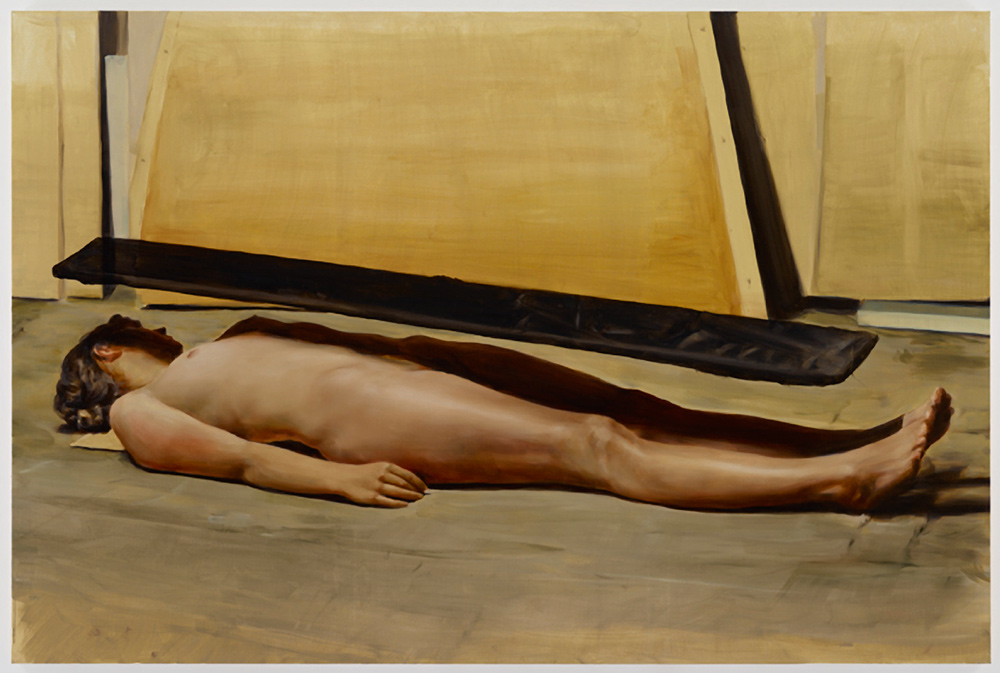

The protagonist in the Borremans painting, The Hovering Wood, encounters a death bell, the great void; she measures her own grave (a la Marlene Dumas), thereby contemplating her scale in the scheme of things, and the ultimate smallness of being. In this work, I see so many others: Manet’s Dead Toreador, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssy, a John McCracken plank; I see that moment in Terrence Malick’s film, Tree of Life, where a dinosaur appears to comprehend itself in a moment embodying both a universal empathy and solipsism, where universe becomes aware of universe. In the same way, she, Borremans’s protagonist in that work, personifies all of us.

Michaël Borremans – Sorcerer

A sorcerer is “a person who claims or is believed to have magic powers;” in a sense, all artists perform magic. Some artist magicians, like Borremans, really do make us believe their tricks, while others, in contrast, just come off as hacks, or even frauds (see: Damian Hirst’s dot extravaganza at Gagosian Galleries worldwide). I’m convinced the real drama in Borremans’s paintings emanates from bona fide spiritual energy — qi, air, prana, the Force. Call it what you will — Borremans doesn’t need to flesh it out for us or explain it, but that numinous energy behind his work is palpable. His paintings allow us to project our own pasts, our own ideas onto his ambiguous subjects. The spaces he’s created — what his boy in the wooden skirt is pressing his hands against — that energy spills outside of the painting into the physical space in front of the viewer. I can’t tell you how profoundly moving this experience is, when you confront his work in person. These new paintings, especially, require the viewer’s presence to complete them. The figures are life-size in scale, unlike much of Borremans’s previous, smaller work; the new pieces infect your mind, and you believe in the sorcery he conjures: that there exists something beyond ourselves that we can, literally, touch if we only allow our minds to grasp toward the impossible.

Michaël Borremans – Painter.

Painting is quite simply the ideal medium for Borremans’s psychologically-charged vision. He circumnavigates our ideas of temporal reality, equally at home in past and present. His touch on the canvas adds an inchoate presence, inaccessible from work in film or photography. His references to space — as a simultaneously physical and mental idea, as both a void and absence of void– serve as a perfect realization of Pablo Picasso’s famous saying, that art is the “lie that tells the truth.” At its core, Borremans’s work perfectly demonstrates the notion that reality itself is relative — it’s not unlike Stephen Colbert’s “truthiness”.

In Borremans’s diptych, The Touch, he elaborates on this relativist vision. As demonstrated by the figure to the right, the model’s extended Pinocchio-esque proboscis corroborates the truthy lie of all painting — that we create our own reality, rather than vice versa.

Noted exhibition details and related media: Michael Borremans: The Devil’s Dress, an exhibition of paintings was on view at David Zwirner gallery in New York City November 4 through December 17, 2011.

About the author: Born in 1978 in South Dakota, Minneapolis/Saint Paul-based artist Ruben Nusz graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota in 2001. He has exhibited work at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Rochester Art Center, Soap Factory and at Art of This. His work is featured in the permanent collection of the Minnesota Museum of American Art; the Walker Art Center Library owns one of his artist’s books. Nusz is also co-founder of Location Books, an independent publisher that provides contemporary artists the opportunity to produce new work in book form. Location is featured in the libraries throughout the United States, including the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art and Midway Contemporary Art. Nusz is represented by Weinstein Gallery in Minneapolis. His work will soon be featured in the Walker Art Center exhibition Lifelike, and his recent paintings will be on display in a solo exhibition at the Kiehle Gallery at Saint Cloud State University.