Backyard Histories: Bethany Lacktorin and Nik Nerburn in Conversation

Artists Bethany Lacktorin and Nik Nerburn gathered in a Google Doc to discuss how their story-based work engages with the contours of local culture, through sound, performance, film, and photography.

introductionIn July of 2018, as part of the Local Practice series on Mn Artists, artists Bethany Lacktorin and Nik Nerburn gathered in a Google Doc to discuss how their story-based work engages with the contours of local culture, through a range of mediums including sound, performance, film, and photography. What follows is both an informal conversation and a kind of digital notebook of projects, each meant to open up space for further dialogue and exploration on the potential for this kind of practice in rural locations.

Matthew Fluharty, Guest Editor

Bethany LacktorinI’m trying to think of a project I’ve done in the last three years that hasn’t involved Nik in some way. I met him in the prairie in the fall and ended up getting kicked out of a landfill.

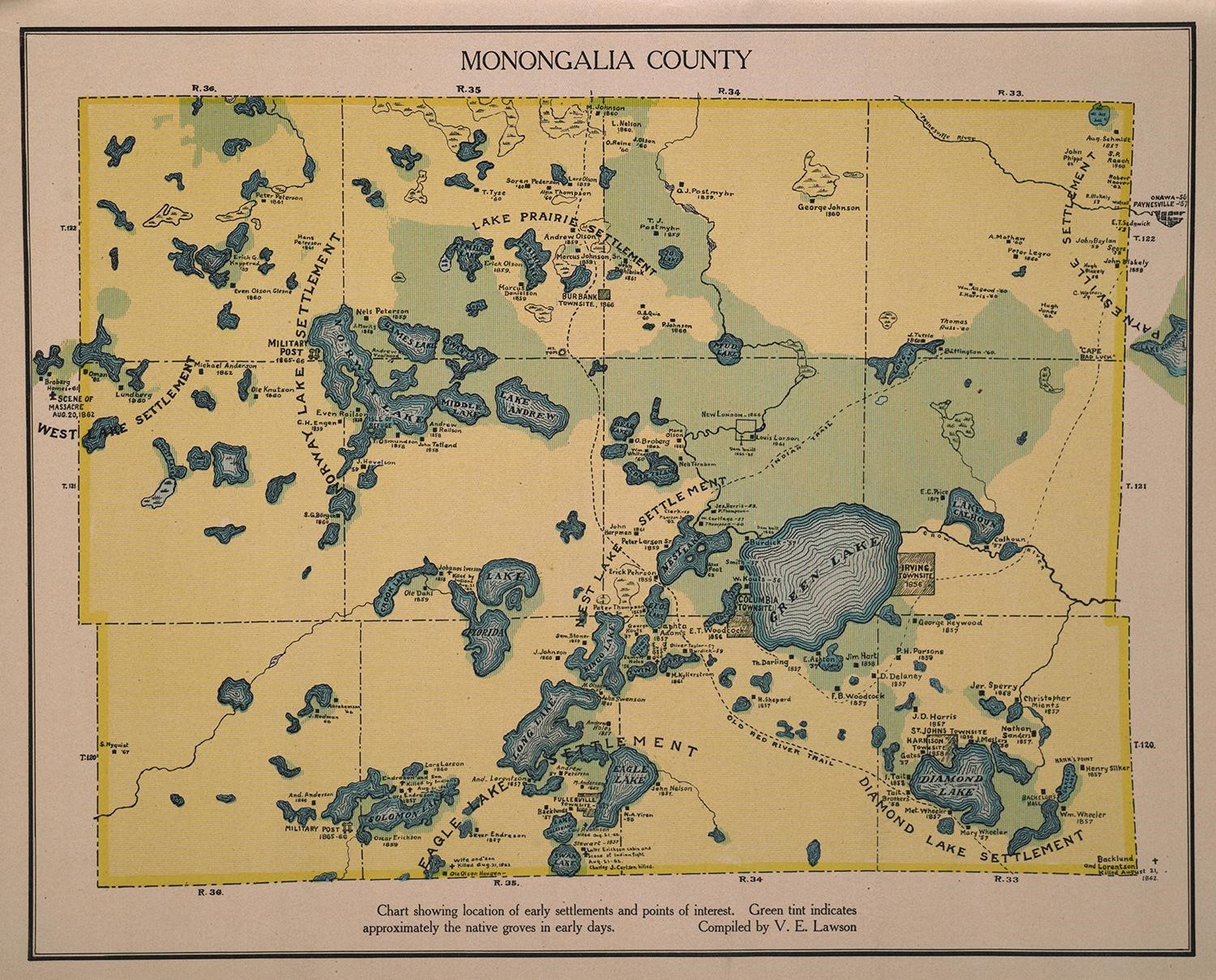

Nik nerburnI remember that! We were working on the nascent beginnings of Jais Gossman’s project about the journey of a real Norwegian immigrant named Ole Knutson, who carried a grindstone from St. Cloud to Brooten, MN in the 1850s. Jais (now Bethany’s fiancé) is still working on that long-term performance about Ole’s long walk, where he embodies Ole and the disappeared Monongalia County landscape in a hilarious and poetic way. (A brief aside: Monongalia County, a beautifully named place, was absorbed into Kandiyohi County at the stroke of a legislator’s pen in 1870.)

Jais, performing as Ole, walked into the county landfill, looking for grindstone analogs and trying on pairs of trashed shoes that he found, while Bethany and I recorded him. It didn’t take long for us to get aggressively escorted out by the landfill staff once they noticed us. That project sealed our working relationship, and it was prescient because it was about landscape and our place within it, which I think most of our collaborations since have also been about, loosely.

This is a map of Monongalia county (now vanished), where Bethany and Jais live. I only really know the work of Bethany’s that’s grown out of this landscape, although she has a wide and diverse portfolio of personal and commercial work that preceded our knowing each other.

blI learned a little about Nik’s process on that first interaction. Or maybe I was witnessing his process evolving as we shot in a 90-degree open field. There was an openness to including the “aperture” in the work—i.e., seeing me hiding behind a bale of hay in the frame was simply not a big deal. I felt that openness in his continued projects. The camera is his partner, not necessarily just a tool, and it finds its way into the finished work.

Your photography projects as “Neighborhood Nik” speak to me—where you’d take Polaroids of folks in whatever town you were in. You documented people in their homes and neighborhoods, and then give them a Polaroid print right there on the spot, and later displayed the images as part of a photo show. You describe those projects as collaborative ethnography:“free family picture days, storefront photo shows, live-narrated neighborhood home-movie screenings, marathon Polaroid portrait giveaways, and rural outdoor experimental cinema screenings”, in your words. In those photos, I see a quite literal self-reflection exercise going on. Your subjects see themselves in the work immediately.

I have a similar feeling when I see your previous work 14 Bales or in 13 Roads in Otter Tail County, because when I view those videos I am put through the same exercise. The vastness that exists in the images allows for my own thoughts and memories to emerge, project into that space and then look back at me. I can see me in those pictures. As a viewer, I am part of that story now. When I made My Ocean and A Steady and Irresistible Wind, I had to go to a very personal, internal place where a lot of digging and confrontation had to happen, in order to understand what it was I was trying to express. In my mind, it allowed less room for audience stories or other narratives to emerge.

nnThat’s interesting, because the photo work of mine that you’re referring to, conceptually, is all about exploring the role of insider/outsider in documentary. Your performance work asks audience members to push themselves, whereas my photo work is all about meeting them where they’re at.

I think I relate to your work, and especially My Ocean, on the level of story. As somebody coming out of a documentary storytelling background, I’m sensitized to narrative. I really like stories. I’m turned on by the personal narrative—the first person, unreliable, contradictory, roundabout stories we tell about ourselves and our histories. My Ocean is a great example of a personal history, specifically about your relationship to the Ordway Prairie, and it captured the complex web of relationships that exist there in a way no straightforward history ever could. It’s a love story, too, but between yourself and the landscape.

It’s funny, because these two landscape films of my own are non-narrative. I have a complex relationship to both Otter Tail County and Highway 2, which is what those films are really about, but the films aren’t about that. Part of the origins of those two films was experimenting with the boundary of moving and still image.

A Steady and Irresistible Wind is less directly personal, in my mind, although it does have a connection to your own adoption, as I recall. I’d be curious to hear you talk about the level of autobiography in that piece.

BlThat’s interesting, because the photo work of mine that you’re referring to, conceptually, is all about exploring the role of insider/outsider in documentary. Your performance work asks audience members to push themselves, whereas my photo work is all about meeting them where they’re at.

nnAnd that happened right after Scaffold got taken down. I remember those swirling conversations we were all having influenced how you framed that history.

blYes, as the storyteller in this scenario, I already had concerns that this story was off limits, that it was not mine to tell. But I still had an obligation to make a piece. This part of the process was a struggle, and I think is the required struggle of artists doing this kind of work. I had to learn to recognize my reactions, my emotions as valuable information with the same standing as the written history and statistics. And if I could take that thought a step further—as artists, we are absolutely relied upon for that information. That’s our job.

nnMaybe that’s something that connects our practices: care for our subjects and audience. The stakes are high when we talk about Native boarding schools, and there’s a right and wrong way to engage with that history.

The series of landscape films of my own don’t directly come into contact with these responsibilities, except for the way they cultivate a certain type of active looking, maybe.

I grew up north of Bemidji, so I spent a lot of time in the car. Lots of driving. Counting trees and telephone poles. Approximating distance and time, following cardinal directions, orienting myself in space, and navigating by landmarks was my early immersion in landscape. Getting to Bethany’s house in my mind’s eye, for instance, is a mental recitation of those details. Highway 71 south from Bemidji (I no longer live there, but it’s my mental mapping starting point), then turn west at the gas station that sells survival gear, and turn right on Highway 104 when you see the barn that’s almost about to collapse (it recently did, so now I miss that turn sometimes.) To me, rural and small town geography cultivates an appreciation for details and their histories, because it’s literally how you get around. You don’t wanna miss your turn!

It’s those landmarks and your tender recitation of them that I appreciated so much about the writing in My Ocean. The peaches at your family’s old store, running with a kite in the driveway, the wayside rest on Highway 104. That geography is personal. Chris Schuelke, the head of the Otter Tail County Historical Society, calls it “backyard history”. I always liked that phrase, and I’ve actually used it to explain to farmers why I want to walk across their potato or corn field to film their hay bales.

blI think in a lot of ways, through exploration of visual and temporal landmarks, our work revolves around a similar need. We’re inviting people to learn our own backyard histories, and learning the ones around us. More than ever, I see artists taking this on. There’s this recent push within policy circles to make sure artists are included in conversations to help solve economic, social, political, mental health, educational and housing problems. When these kinds of collaborative situations become more commonplace, we can really begin to build something out of our amazing patchwork, out of all the layers. Something that becomes a story that can be all of ours to tell—a collaborative ethnography. A story we can share.

This piece was commissioned and developed as part of a series by guest editor Matthew Fluharty.