At Home in the Present: Ann Jenkins and Stephanie Richards

Two shows by radically different painters at the Duluth Art Institute Depot galleries (506 W Michigan St.) spur thought about the potentials of painting itself.

“Dialogue with the Landscape: New Paintings by Ann Jenkins” (through August 5, artist dialogue May 24, 7 pm)

Residency: New Work by Stephanie Richards (through July 8)

Two current shows at the Duluth Art Institute, in neighboring galleries, aren’t meant to be related. But they illuminate each other, and shed light on the ways that painting creates meaning. They’re both about home, but couldn’t look more different.

Ann Jenkins paints the landscape. Her work nods toward the abstraction of Milton Avery, but doesn’t go as far in the direction of abstraction as, say, Arthur Dove, who strove to make paintings that had no visual references. She loves the paint, but doesn’t depart from the subject before her eyes. She notes, “I believe that the tie to the physical world is imperative because it is the natural world from which all vision originates and which sustains us as human beings and as artists.”

For her, the physical world is the natural world. She’s at home there. Her work has developed, gradually, into a style that’s instantly recognizable, and much beloved in her home region. You’ll find Jenkins’ paintings on the walls where people gather to regale themselves with intelligent sensuality (like at the New Scenic Café on the North Shore of Lake Superior).

The forms of the landscape around Duluth and its trees and grasses are in her work; the paintings’ color is derived both from her subjects and from her pleasure in them. It’s no secret why her work is popular. She takes the often demanding and antisensual boreal realm—to a mammalian body traveling through it, it’s often cold, stony, wet, austere– and translates it into a landscape of visual perception: full of changing lights, unbelievable colors, a matchless scale.

She paints a northern world in which extreme sensations and the cultivation of perception create a mental world that parallels the physical one, that longs for it like people long for spring. In northern Minnesota, where being outdoors is often difficult, people spend a huge amount of time outside, and even more time imagining being there. This sensual paradox can be seen in much northern landscape painting—you’ll see it again in the show of Scandinavian landscape painting upcoming at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mirror of Nature: Nordic Landscape Painting, 1840 – 1910)

“Home” for Jenkins has little to do with houses, at least in her paintings.

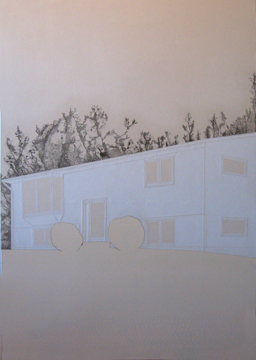

Stephanie Richards, on the other hand, for her show painted only houses—in fact, every house she’s ever lived in. Considering how young she is—just out of art school at University of Minnesota-Duluth—there’s a lot of them! But they are meant to show, somehow, their inverse.

She says, “Although the homes depicted are my own, the personal detachment expressed through the style of rendering presents the images only as a [house]. . . . The nostalgia of a certain image of a house to connect with when away is nonexistent. Instead it is the horizontal line of a body of water that I long for and recognize as home.”

Her paintings are spare, painted thinly, laid out with stencils, largely black and white. They’re beautifully done, subtle. The most evocative ones are houses at night, their rectangular forms just barely poking out of the dark-grey gloom, no lights in the windows. They’re sort of anti-Kincaid houses, buildings that refuse a sentimental construction. Their very numbers seem to dismiss any notion of a house as a home, as a singular place.

Instead, Richards, like Jenkins, claims the natural world, a landscape or rather waterscape, as home. Wherever water stretches to the horizon is home for her. But this she does not represent. The paintings are the obverse of it, limning it by absence.

Both shows occupy the same ecosystem, but they react to it in radically opposed ways. Jenkins has, if anything, too much faith in painting. She trusts it to store and show forth the place, her perceptions of it, her love of it. She trusts it to simply say what she means, what she tells it to.

Richards has, by contrast, a real distrust of traditional strategies of representation. Her student work contained a lot of ambivalence about art in general (one work consisted of stockpiled drawings and paintings crammed into a small space: a lot of work, not valued, not cared for, deliberately presented as orphaned or without use). The contrast between her professed visceral idea of home (the watery horizon) and all these quite elegantly painted anonymous dwellings shows her distrust of art’s ability to represent by anything other than negation or exclusion.

About forty years separates the two artists; those years have changed ideas of what art can do. These painters are intelligent and engaged. Their juxtaposition invites thought about how painting as meaning and communication has transformed itself over time, and continues to do so.