This Body Is Not a Temple

Transdisciplinary artist Christopher Corey Allen offers a slippery exegesis of the punk∞body: drawing on iconic punk moments, queer theory, and their own artistic research, they excavate punk as a practice of generative refusal, anti-containment as a gesture towards fluidity, and messiness as a language of dissent.

I was 10 years old the first time I connected sound to rebellion and self-actualization. I stole my brother’s The Clash album out of his room and turned my mixer to 11. What came out of the speakers hit hard, nearly knocking the wind out of me. Never had I heard such speed and distortion. I was alone in my room but I instinctively jumped up to see if anyone else was hearing what I was. Of course they weren’t, the only others in the house were violently arguing upstairs, as they would for years. At that age I was just starting to form a foundation of opposition to a lot of my surroundings—my family, my city, my friends—and struggling to understand why I felt different. Hearing this song, its affect was instantly translated into a sort of understanding, a new knowledge of self, of anger, of determination. The unorthodox rhythm and speed made me move in new ways. I became aware of my ability to create new movement, without structure, without a need for understanding why. There was a comfort in having a certain type of sound speak to you. And then to have a burning desire to hear more. If a sound can move you in new ways, maybe I can think in new ways. Maybe there is a way to create space for your own thoughts and desires. To create a belief structure that is not dictated by what you’re told, but rather what you feel.

How can sound embody action?

What does action look like?

Why do I crave this action?1

PUNK BODY∞PUNK FEELINGS

A large part of my artistic practice is informed by my formative years growing up in the DIY punk community. I draw a relationship between the messiness and fluidity that characterize my own queerness and its constant in-process construction of identity. In this, oppositional notions of success and failure are broken down, and a kaleidoscopic understanding of identity is possible. My work aims to contribute to the imaging of that kaleidoscopic space, where the borders of normativity and binary systems are tested, and bodily deviations from the social can render the capability of a more radical, present future.

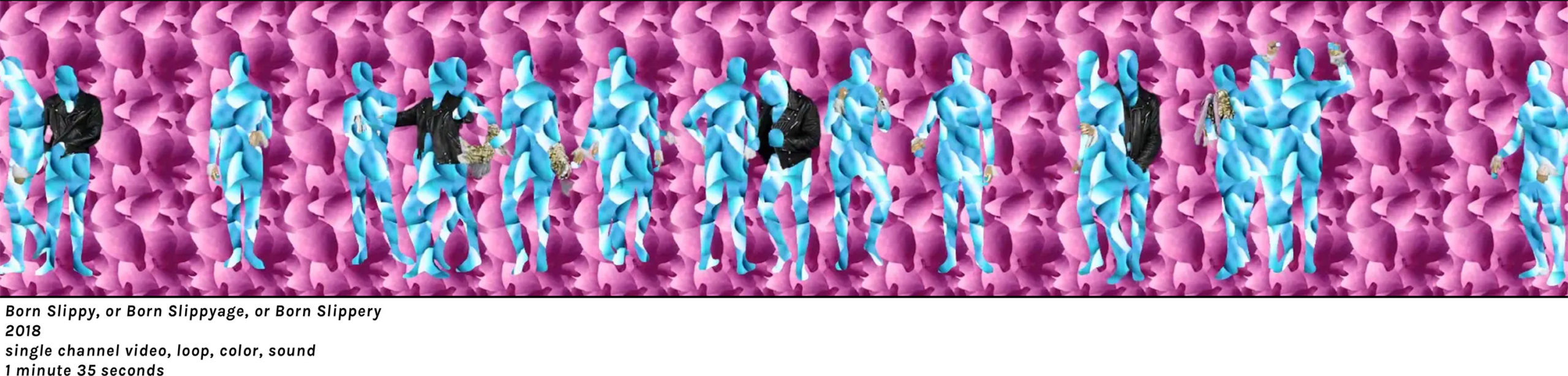

[i]

This is an evolving investigation into how my experiences in DIY punk culture have influenced the way I move through the world. It is part of an ever-expanding body of research that informs my artistic practice, as well as my ability to understand myself, heal, and continually adapt to life under late capitalism. I am interested in this as one of many ways of thinking about being, mentally and physically, not bound or contained. We are unfinish(ed/able) subjects, whose transgressions and contradictions can create a messiness, putting us in a constant state of becoming2. It is a way of thinking that is solidly rooted in imagination, speculation, and the belief that anything is possible. Here, I use some examples from early iconic punk moments, their intersection with queer theory3, and in relation to performance: onstage, in cinema and in daily life. I use this as a method for self-actualization that helps me to understand the formation of my own identities, and as a way of interpreting my own artistic practice—of which some examples are included here. It is meant to be non-linear. We do not follow linearity. It is by no means comprehensive, accurate, or complete. Punk defies categorization. Therefore, it is an attempt to categorize the uncategorizable, which is both hopelessly punk, and a deathblow. So let it be a practice in letting nostalgia wave over me, and for a short time, it’s all right.

“To those who will say that I can’t have been a real or true punk, let me reply in the words of Geoff, there is no such thing as punk, and therefore no basis for the distinction between real and pretend. Punk is what you make it.”4

To be punk is to be a multiplicity. It’s a belief in the self and a belief in collectivity. It can be adorned in leather, studs, dyed hair, nose rings, hard and sharp. But it can also be lycra, platforms, soft & billowy. It can be aggressive, loud and fast, but it can also be passive, slow, quiet—anything it fucking wants. It is not just a fleshy sack that is to be maintained and kept alive, it sneers at a cartesian binary. It is everything that comes with that sack; our fears, thoughts and desires. Utilizing all forms of resistance and liberation, it pursues a life of generative refusal. Dancing around utopic and dystopic, it is where fuck you means why not.

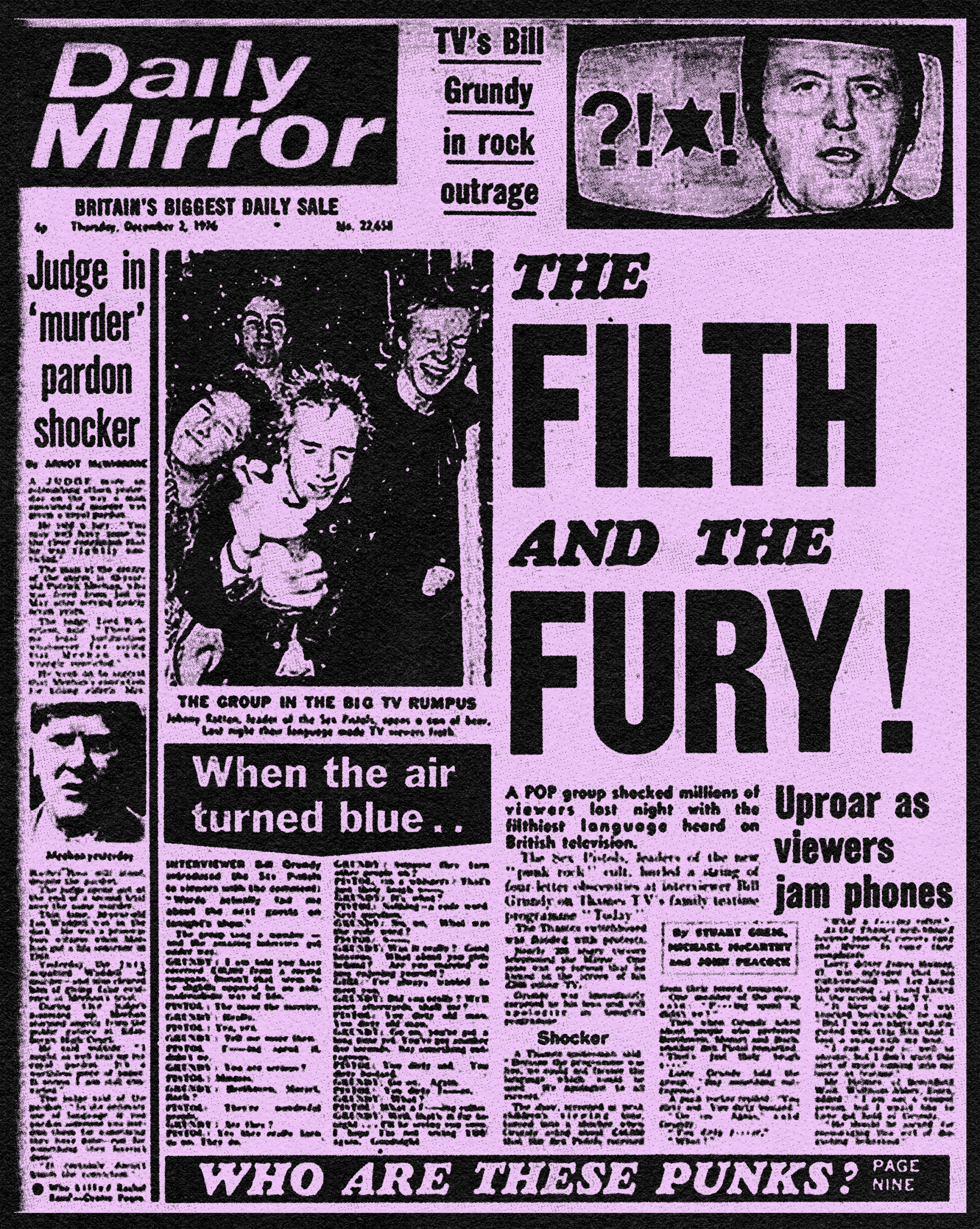

Which brings us to 1976. The Sex Pistols, a punk rock band from London, were being interviewed on live television when guitarist Steve Jones said the word fuck, sparking national outrage that went all the way to parliament.5 It wasn’t the word that Steve Jones said but what it represented. Things that were traditionally seen as indecent and grotesque were being brought out in the open.

[ii]

Punk started as a reaction to values of modernism. A place populated by different kinds of renegades: new immigrants, queers, women, and social misfits.6 It was permeated with new attitudes of skepticism, irony, or rejection toward the metanarratives and ideologies of modernism. Initially, punk was a response of extreme disillusionment with systems of authority that developed in the aftermath of the failure and disappointments around 1968, which saw uprisings led by leftist groups, anarchists, surrealists and Marxists-students in Paris, Mexico City, Rome and many other cities across the world.

They demanded, among many things, a more participatory, grassroots democracy, and decentralization of political and economic powers. One of the slogans that came out of these movements was Be realistic: Demand the impossible! So punk! What followed was a reactionary state crackdown that redirected the political scope towards neoliberal policies, and punk developed directly in relation to this political shift. Where success and perfection was the ultimate individualistic goal of neoliberalism, collectivity, self-expression and a refusal of perfection was the goal of the punk. It made it a point to bring repression out into the open through transgression and deliberate attacks on neoliberal values.

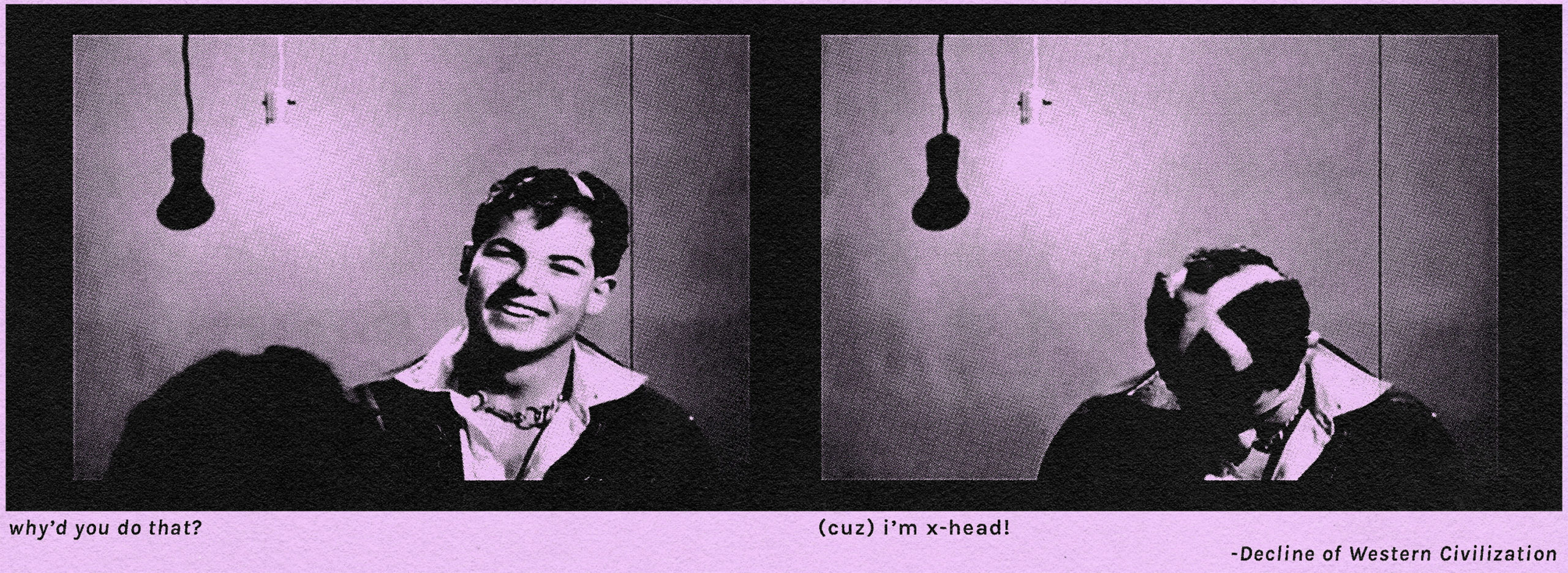

[iii]

Led by the aesthetic and acoustic distortions of punk rock, which values the amateur and sloppy play as form of success, punk became a symbol of opposition and an assertion of power. It wears the messy as a badge of honor, and created a form of resistance against culturally agreed value and taste. Embracing aesthetic and behavioral fluidity, gender identity/presentation and sexuality become abstract7 from a normative understanding. This all blurs into a beautiful mess that I refer to as a punk∞body (miniscule intended). For our purposes, ∞ represents the acceptance of the limiting nature of language and acts as a visualization of the constantly shifting link between these two insufficient words. It also signifies an understanding of the infinitely unorientable and speculative nature of the ideas held within them.

DAILY HISTRIONICS

In Performance Theatre and the Poetics of Failure, Sara Jane Bailes notes that performance of the body in society is a form of specialized labor, where failure of that body to perform as expected can become political critique. She cites an example where cultural critic Walter Benjamin experiences an error of presentation in a production of the tragedy Le Cid. In it, the actor playing the king is wearing a crooked crown. This moment of rupture has an alienation effect on the audience, inducing both familiarity and unfamiliarity at the same time.

The audience is simultaneously aware of the labor of the performer, while also being aware of whether or not they are “good” at it. This rupture creates the possibility of showing more than one thing at a time, revealing more than itself as it illuminates the duplicitous systems entangled in its operations.8

[iv]

In John Waters’ 1974 film Female Trouble, the main character, Divine, wants to get the electric chair so badly. To her it’s like getting the academy award for her profession.9 She continuously and deliberately fails to perform her role as a good daughter, a devoted wife, a loving mother, or more generally a proper lady. Her struggles and the way she copes with them are both familiar and exaggeratingly unfamiliar. The space in between these familiarities is where a punk∞body lives. It fails to perform its societal given task properly, whether that be the hegemonic fantasy of a healthy lifestyle, a nuclear family, proper hygiene, financial success, etc.

[v]

Stuart Hall’s and Jack Halberstam’s concept of low theory can be used as a way of understanding a punk∞body as an error of presentation. They see low theory as a way of embracing failure as a counterintuitive form of resistance, a way to inhabit the refusal of mastery and success. It entails a willingness to fail and to lose one’s way, in order to pursue difficult questions about complicity.10

This allows us also to think about a punk∞body in relation to failure. It creates a disorganized path between seemingly opposing styles that have been set up to determine value, desire, and etiquette. It doesn’t just try to fail, but it sets a new way of understanding failure as a form of success. It is messy in that it blurs the lines of merit to a point where evaluation is infinite or impossible. Punk gives us an example of how failure is an intentional practice, or as social theorist Jacques Attali calls it, a “formidable subversion,” a breakdown of perfection as a value, something that ensures security and reliability.11

[vi]

Theorist Roland Barthes’ ideas of the body as a topos, strange & unfamiliar, is relevant to a punk’s view of their own body. To Barthes, the body is “of a ceaselessly unforeseen originality, that resists description, definition and language.”12 We are our bodies, and yet always our bodies inevitably are unfamiliar to ourselves.

A punk∞body acknowledges its own slippage. It accepts messiness as an inherent part of the act of performing oneself. Through its insistence that the body is not a temple, it seeks out failure.

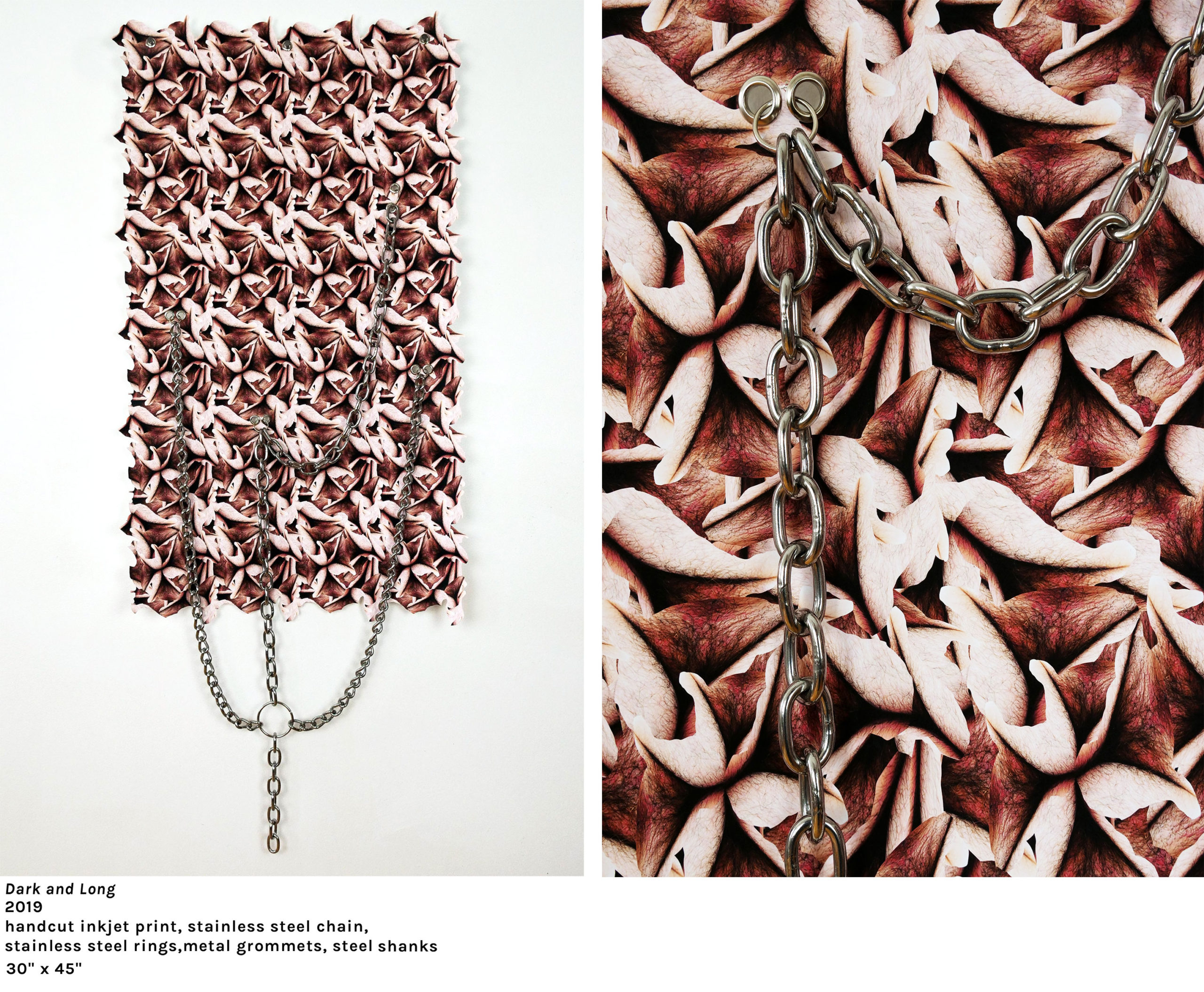

[vii]

This can occur through a rejection of a normative healthy lifestyle, where habits such as alcoholism and drug abuse indirectly become a form of social critique and deviance. It is by no means a requisite of a punk∞body, but is often a part of the culture.13 I am not interested in a sort of spectacle gaze of addiction, and as someone who suffers from addiction, I am not interested in glorifying it. But in its behavior it represents a way of moving through the world that is not cohesive. It is a refusal to secure a certain kind of functionality that capitalism requires of the body, in order to support productive forms of labor.

Of course, the daily realities of addiction are conducive to a lessening of understanding and an incoherent refusal over the long run. And yes, it disrupts neoliberalism’s personal success story, but it is also incredibly damaging. If your sense of power comes from a belief in self-determination, addiction can throw a pretty muddy light on that. But disregarding its existence and refusing to understand its significance would be a deliberately utopic form of failure.

[viii]

THIS BODY IS A DIRTY BODY

John Waters once stated that if he could get the audience to throw up while watching one of his films it was a sign of success.14 In this is a rejection of the body as pure and stable, a rejection of a body that has reached or can reach perfection. A punk∞body utilizes its bodily functions in its performance.

[ix]

For Iggy Pop, it was a way of telling his audience that he is not an idol. For him, throwing up onstage was simply a way of reminding the audience that we all share this body full of juices—and why not show how it functions in a celebratory manner, with a little bit of style? As a deliberate fight against the embodiment of perfection, it works “aggressively against containment of bodily fluids and the integrity of the individual and the social body, its excess works against the perceived harmony of good form”.15 It is an acceptance of bodily functions, which denies the existence of a perfect body, allowing every body to fail. It is a way of politically weaponizing these functions. Anti-containment of bodily fluids is a political act of disregard for the societal containment of the body.

[x]

Singer Poly Styrene upended the notion that cleanliness is next to godliness by using satire in her band X-Ray Spex’s song “Germfree Adolescents”. Poly calls for an embracement of dirtiness as a refusal of society’s standard notions of beauty and cleanliness. She saw a punk∞body as a filthy body. And through the behavior of an anti-expectation of normativity, everything is possible. So being dirty, literally dirty, is a way of opening possibilities.

BREAKING THRU

Punks were trying to figure out a way of saying to larger society that they wouldn’t be held by anyone’s standards of measurement: they aren’t going to measure at all. Greil Marcus describes the experience of punk’s desire to change the world as a desire that

“begins with the demand to live not as an object but as a subject of history—to live as if something is actually depending on one’s actions, and that demand opens onto a free street . Damning God and the state…[it] made it possible to experience those things as if they were not natural facts but ideological constructs: things that had been made and therefore could be altered, or done away with altogether.”16

At its very core, a punk∞body is in constant flux. In its flux over the years, it has taken on more aesthetics, behaviors, politics and forms. There is a mistake in doing exactly what I have done with this writing: naming the thing, thus giving it a set structure and containing it. But this is not to take away from the initial cultural impact punk had and, to this day, maintains. It created a new language of dissent17 that put such things as purposelessness and disposability into the spotlight, and made them a threat to the hegemonic standards of the time. It gave people new ways to think and express their desires and needs.

All I’ve done here is taken it from a mere moment and tried to slow it down. But it’s flying at a million miles an hour, and in its constant state of motion it is in a constant state of expectation…of breaking thru. It will never stop because the untamable can never be caught.

[xi]

This article is part of the series by guest editor Kristin Van Loon.