Art Review: Scott Murphy, “New Narrative Paintings”

Julia Durst reviews "Scott Murphy: New Narrative Paintings," at the Duluth Art Institute's George Morrison Gallery through December 7. This review was first published in the Ripsaw News, a Duluth tabloid.

Scott Murphy’s show of paintings at the Duluth Art Institute struck Ripsaw News reviewer Julia Durst as “stunning and strange.” I’ve seen the show, and it is incredible. If you’re in Duluth or if you’re passing through, see it. Murphy makes painting–the process as well as the product– really matter.

–Ann Klefstad, editor

Vapid art has its place. In dentists’ offices and hotel lobbies, it serves its purpose: being pretty but not provoking too much thought. Benign and inoffensive, it wallpapers our lives. Obscure art has its place too. Conceptual and dense, it can incite debate and entertain art historians. It’s the kind of art that Joe Schmoe often scoffs at, mumbling “I don’t get it,” expecting that there’s always something to “get.” These days, beauty and content rarely coexist in equal parts. That’s what makes the new paintings of Scott Murphy so remarkable. They are luscious examples of what oil paint can do, but they’re also puzzles, image and title combined, then handed over to the viewer to decipher.

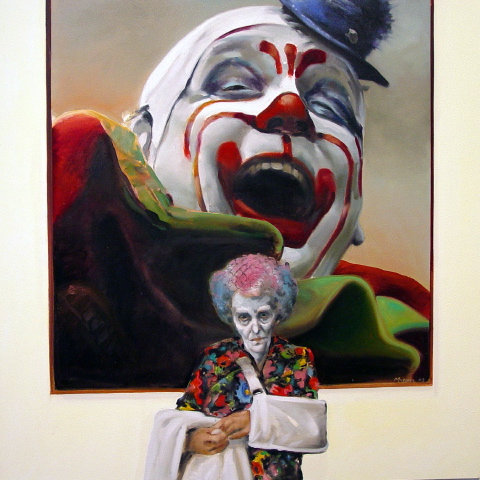

In his current show at the Duluth Art Institute, Murphy’s perplexing work fills the gallery with presences akin to 19th-century European masterpieces. The space hums with the warmth of rich browns and fiery oranges, solemn grays and subtle yellows. Each elaborate frame houses a separate world, a brief juncture from a larger unknown timeline that implores the viewer to fill in the blanks. In fact, the show’s title “Narrative Paintings” is something of a misnomer. There isn’t so much narrating—as in, representing of a story—as hinting. It’s kind of like when you walk by two people who are talking and catch one or two phrases of their conversation. Taken out of context, such pieces of meaning are amusing, confusing and infinitely interesting.

Murphy’s work varies in its difficulty of access. Sometimes the painting’s meaning is quite clear, as in “Birth of Venus,” which shows an infant in a shell-backed high chair in a kitchen that’s mysteriously adrift at sea, referencing Botticelli’s famous painting of the same name. Sometimes the meaning is more elusive, as in “Andre’s Wandering Accordionist,” a surreal image of two men (one playing an accordion) in a room half-submerged in water. Some paintings are so beautiful, so incredibly vivid, you may find yourself locked in a staring contest with pigment and forget to grope for meaning at all. “Until Someone Gets Hurt” has that effect. The painting depicts clothes strung up to dry on a backyard clothesline. Nearby a young boy in football gear and a majestic horned mammal (a moose? a caribou perhaps?) appear poised to start a game of some sort. The scene oozes a quirky wholesomeness, but it is the colors that will hold you there—so sticky sweet your eyes lick them up.

There is a certain darkness to much of Murphy’s work as well. In some, it comes across as creepy (“Burning Ants With His Son,” a painting of welders engaged in some sort of seemingly religious experience) and in others simply sad (“Bread and Circuses”). Even as he uses wordplay and sharp wit composing and naming his paintings, Murphy retains sensitivity to the human condition in how he records people. There is tenderness, honesty—it is evident the artist’s hand is experienced at more than painting.

Murphy has been painting for decades, having received his BFA in painting from UMD in 1975. He works as a union painter and lettermaker full time, somehow still finding time to devote to his oil painting. It is curious to think that Murphy experiences the same draining, droning work world as the rest of us untalented schlocks, only he has this amazing visual language through which he can respond and invent. The result is stunning and strange, sometimes haunting, but never sinister. It pulls you in by not only your eyes but also your brain. Neither vapid nor obscure, Scott Murphy succeeds in proving that beauty and content are not mutually exclusive.