Art Review: Postmodern Baroque?

Franklin Art Works is showing Bruce Tapola, "New Paintings," Francis Gomila's video "A Place Called Oxmoor," and Clea Felien's "Portraits." Three entirely different bodies of work--how do they compare?

After viewing the current show at Franklin Art Works, I was wandering the city, puzzled about how to begin a take on Bruce Tapola’s new work. I went into Cumming’s Books in Dinkytown and, flipping through the art books near the door, stumbled onto Peter Schjeldahl’s 1987 book on David Salle. Aha! I thought, a near analog to Tapola’s image-fields. When Schjeldahl wrote of the ‘80s new figurative painters that they “treated imagery as nature,” it seemed even more apropos.

Schjeldahl appears to be using the word “nature” to designate that field of raw material out of which painters work, the dominant world of appearance that is seen as the container of the most significant meanings of the culture. Nineteenth-century plein-aire modernists thought of the forests and fields as being this realm; early twentieth-century modernists (think Ash Can School as well as Caillebotte) thought of the urban street this way. Many figurative painters of the ‘80s onwards thought of the entire world of imagery, from magazine ads to porn to high-art reproductions to movie stills to . . . as that raw material, as being the “forest” of the current world.

Of course this began with Pop, but in the ‘80s a far more thoroughgoing exploration of the potential of this insight began. Some examples of it—Sherrie-Levine-style “appropriation,” say—were dull, really just art-school attempts to address aesthetic or ontological “problems” limited to the artworld—and who could be expected to care about this except art-world insiders? But some artists, including Salle in New York or Sabina Ott in California, made interesting attempts to derive their work from a sort of telescoped museum of all the imagery humans have ever made, from cave paintings to Baroque court imagery to still lifes to Vogue models to old episodes of Lassie.

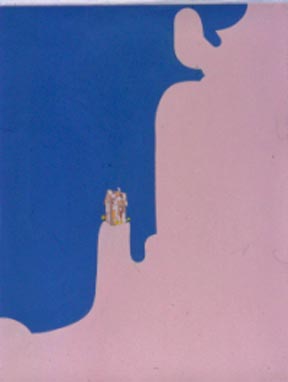

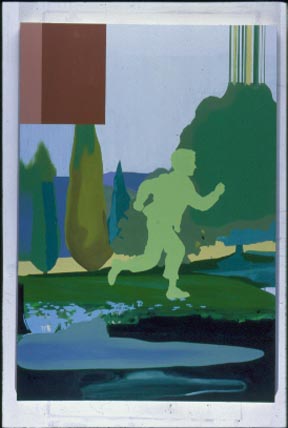

This appears to be the matrix from which Bruce Tapola is drawing his imagery. It’s so diverse it could have been made by 3 people, and it clearly derives from popular-culture sources. Some of the paintings in the show are old movie stills; some have the look of cartoons coupled with ad-layout lozenges of flat color. This isn’t work that’s very accessible to most people, though, except in that they can easily seize its look and align their expectations correctly. Once aligned, though, it’s hit or miss whether they actually get any individual piece—the work has superficially appealing qualities that don’t seem to lead anywhere.

In the past Tapola has constructed environments hinting at stories that tie his imagery together, serve as interpretive guides. Maybe something like that could be developed for this diverse body of work, a set of layered stories that intersected, maybe a set of fragments keying together at crucial imagistic points, a text or a hypertext—something to make the fragmentation, as well as the individual fragments, make sense, or at least allude to sense.

The other components of the show—Clea Felien’s oil-on-paper paintings and Francis Gomila’s video installation—are less problematic. Felien’s drawings, backed by beaux-arts training but refusing that training (she does these with her left hand, not her dominant right), continue to become more complex, and are engaging the potential of technique in an interesting struggle.

The video installation is very moving, I suspect in large part because of the evocative musical fragment that accompanies the imagery, likely (though I’m not sure) composed by the artist, who is also a musician. The video consists of a series of seamlessly joined one-and-a-half-minute recordings of the apartments of the residents of Oxmoor, a poor community embedded in a wealthy region of southern England. The videos are taken by a tripod-mounted motor-driven camera that makes one rotation from the center of the room for each space.

The occupant of the apartment is always present somewhere in the recording, self-conscious, sometimes serious, sometimes smiling. There is great pathos in the subjects’ attempt to live up to the occasion and to his or her sense of self, despite such subjects’ evident knowledge that one’s appearance cannot deliver this sense of self but will instead telegraph a much more miscellaneous impression. It’s not excruciating because one watches the video in solitude, one’s voyeurism excused by the humanistic strains of a violin playing a short evocative passage reminiscent of, say, Berg, or early, romanticly-inflected Schoenberg. The violin passage is longer than the 90-second image segments, and so isn’t heard as programmatic or illustrative. Rather, it serves as a guide to the solitary viewer—a permission to see these people in their cluttered spaces as fellow-humans, as touching in their vulnerable presence.

As you can tell, I’m not entirely trusting of this video. No doubt it was made in the best of faith, but I sort of long for someone on the video to make a face, hoist a middle finger, not act like the deserving poor. There’s a little girl, about 10 years old, that comes the closest to this, and her silent laughter opens a little rip in the smooth beneficence of the presentation.

These three bodies of work together cover a great swath of the current artworld. There’s been much interest lately, from a number of quarters, in a postmodern Baroque—that is, an art that accepts its dependence on previous eras and revels in it, rather than approaching it on coy tiptoes. In this exhibition, Felien’s work does this best, revelling in the immense potential of the historic. She takes her life and her painterly skills in, literally, both hands and uses whatever she wishes of them without qualms. Tapola could use more of this, could serve some clearer notion with more heart. Smartness in art, like smartness in anything, is only as good as what it brings about. Tapola’s smart work seems to spin its wheels.