Art Review: Placelessness in American Life

J. Z. Grover reviews an exhibition of a turn-of-the-century Minnesota artist at the Tweed Museum in Duluth: "Gilbert Munger: Quest for Distinction." The show runs July 26October 12.

The U. S. Postal Service (USPS) tells us that the average American residency is only eighteen months long and growing shorter. What do people who move about see that those of us more placed do not? What do they overlook that we see?

In the case of a visual artist, a painter, the plasticity of vision that touching down only briefly encourages can create a body of work so discontinuous that it fails to add up to anything with weight. Gilbert Munger, a landscape painter of the 1860s–1900s, is a case in point.

The Tweed Museum of Art in Duluth has mounted a large (73 works) retrospective of Munger’s work based on the research of a true amateur, California software engineer Michael D. Schroeder, and art historian J. Gray Sweeney, using paintings held by the university and others borrowed from public and private collections across the country.

Munger’s life was as restless as those of the USPS’s most transient customers. Born in Connecticut in 1837, Munger moved to Washington, DC, in 1850 to apprentice as an engraver. There he saw his first heroic landscape paintings and aspired to make similar canvases. During the Civil War years, 1862–65, he served as timekeeper to a defense project and painted on the side. His timing was auspicious: the war years created an immense visual appetite among newspaper and periodical readers that was satisfied by field sketch artists and photographers. This appetite, along with the halting of government geographical surveys and construction of railroads during the war years, created an immense market for images of the opening of the American West in the years following the war.

As a young artist on the make, Munger followed this emerging market to New York City. His first large-scale paintings were calculated to satisfy popular curiosity about unseen landscapes. For example, “Minnehaha Falls,” painted during his stay with his two brothers in St. Paul in 1867–68, excluded the bridge built below the falls and instead inserted two stock Indian figures in the foreground, thereby annexing the painting to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s popular poem, “The Song of Hiawatha.”

Munger’s other large-scale Minnesota canvas in the show is “Duluth” (1871), one of those subjunctive, Westward-the-course-of-Empire-takes-its-way paintings so popular in the postwar period. Duluth—a town that would become all but abandoned by 1873—was depicted with a ship canal, a dredge, a railroad—all things that would come to it eventually. The painting, not surprisingly, was bought and hung in a Washington, DC, hotel that catered to congressmen and lobbyists.

Soon after painting these canvases, Munger left Minnesota, returned to New York City, and within the year managed to get himself invited as a guest artist on Clarence King’s federal Geological Survey of the Fortieth Parallel. This and other of King’s surveys, the most lavishly financed and longest-lasting of post-Civil War government surveys, included at different times the Civil War photographers Timothy O’Sullivan and Andrew Russell and the San Francisco-based photographer Carleton Watkins. In their company, Munger sketched and painted the American West. Their influence is evident in his Western canvases, whose perspective is sometimes identical to the photographers’ (for instance, “Lake Lall and Mount Agassiz, Uinta Range, Utah,” which mirrors O’Sullivan’s spliced panorama of the same scene). The surfaces of Munger’s paintings from this period are smooth and highly detailed, their contrasts similar to the long continuous tones of wet-plate, printed-out photographs. Some of Munger’s sketches and paintings were adapted as chromolithographs in the volumes King later published to document and promote his surveys.

In San Francisco, Munger quickly assessed the market among that city’s wealthy businessmen for heroic, highly detailed canvases of western landscapes and began producing them. Like those of Albert Bierstadt, many of Munger’s paintings were vast, hyperbolically lit, and intended for the cavernous California mansions where I first saw them: the Crocker and Gallatin mansions in Sacramento, the Spreckles and Stanford ones in San Francisco.

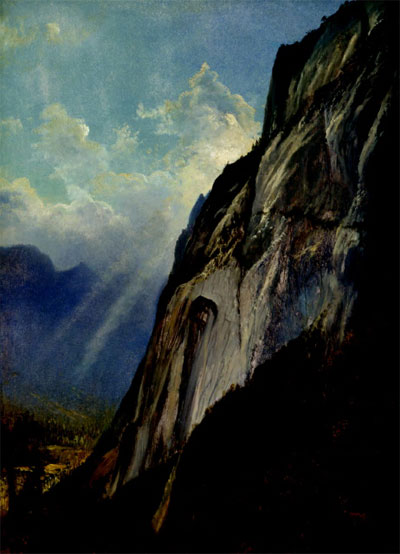

These were Munger’s boom years. Introduced to San Francisco “society” by the well-placed, Yale-educated explorer Clarence King, Munger shuttled between San Francisco and New York, painting heroic landscapes for his western and eastern admirers. He depicted a West designed to awe viewers, if not by the vastness of the land, then by the drama of its lighting. (I have to say that in most of his California landscapes, with the exception of his Ocean Beach, San Francisco, paintings, Munger’s lighting strikes me as wilfully false; like his visual successor, the photographer Ansel Adams, Munger couldn’t seem to leave California’s largely untroubled skies alone, instead insisting on piling up contrasting clouds [as in “Yosemite Valley from a Cliff,” n.d., ca. 1870–75] or unreal contrasts [“Redwood (Sequoia) Forest,” n.d., ca. 1870–75] to heighten their drama.)

After less than a decade of restive survey and salon work, Munger left his studios in San Francisco and New York for Europe. The Gilded Age’s giddy economy had caught up with his patrons; the Panic of 1893 had ruined some of them. Munger had been urged to visit Britain by some of Clarence King’s wealthy acquaintances, and by mid-1877, he had followed them to London.

What had been meticulously, even photographically, detailed paintings of the American West now morphed into a variety of styles. In Britain, Munger was successively influenced by John Millais, John Ruskin, and J. M. W. Turner. His paintings in Millais’s and Turner’s styles (such as “Landscape with Hiker and River,” ca. 1877–79 and “Venetian Scene,” ca. 1882–92), the latter all sfumatous atmosphere, are technically accomplished and utterly impersonal—painterly essays in another’s cultural sensibility. Munger was welcomed in the world of well-upholstered, conservative art patrons, and he responded by acquiring a posh English accent, a fictively genteel background, the status of a gentleman, and an urge for remaking himself once again.

This he did by moving to Paris, where, he apparently lived for six years (1886–93). Like the artists later characterized as the Barbizon school, Munger painted forest scenes in Fontainebleau. Unlike his Western paintings, these were rough-textured canvases that depended for their drama on the deep, forced perspective made possible by the flat landscapes of broad river valleys.

Like Munger’s Venetian and British landscapes, his French ones strike me as superficial: they are about the transient effects of light and surface on generic landscapes. Unlike, say, Cézanne’s patient deconstructions of Mt. Ste. Victoire, Munger’s European canvases focus not on known, explored places but on painterly gestures. In this sense alone, perhaps, Munger could be said to be a modern.

Put another way, he could be said to be an archetypally displaced person: an artist who had to depend on more placed artists for his cues, since he himself was not culturally attuned to what he saw. A painting like “Neue Reuilly” (1889) is a case in point: the trees and light lack specificity: one couldn’t characterize this scene as depicting morning, midday, afternoon, or evening light; its trees are strictly notional.

Munger recrossed the Atlantic in 1893, aged 56, intent on “earn[ing] that recognition in my own country which I have won abroad. I should like to identify myself with the people of my own land and take an interest in their art life.” Between 1893 and 1903, when he died, Munger moved between New York City, Duluth, and Washington, DC. He continued to paint landscapes that were mostly domestic-scaled and filled with harvest shocks of corn, orchard trees, glimpsed farmhouses, and flocks of chickens. He painted remembered French landscapes as well.

The art market passed him by. It is jarring to recall that Munger was still painting his serene, umbered landscapes shortly after Alfred Stieglitz opened An American Place, before the Armory Show signaled a deep shift in what painting in America could be and mean.

Munger’s last years were lived in Washington, DC, in increasing poverty and obscurity. He did not paint Washington; his last known canvas was a portrait of Niagara Falls that depended for its power on dramatic lighting (including a rainbow) and monumental scale.

What does Munger’s life as an artist add up to? How do we make sense of a career that, in the words of art historian Alan Wallach, was “art-historical[ly] nondescript, impossible to pigeonhole and therefore impossible to assimilate to the sort of history of art that relies on conventional narratives of style and stylistic evolution”?

For me, Munger’s work demonstrates the weakness of American mobility. He was free to move—he moved; he never settled anywhere long enough to know it well. Out of his element everywhere he went (change was his element), he was drawn to the most dramatic, but often humanly least significant, of landscapes. He picked up deftly on the stylistic traits of painters far more embedded in cultures and places than he, and he replicated the visual traces of their involvement without their depth of observation.

He returned from Europe, like so many of his own and the preceding generation of American artists, to a country he no longer understood, and here he found that the market—and the culture—had changed and no longer wanted what he could offer. From being voluntarily displaced, he became an involuntary, internal exile. Bitterly, Munger learned that he was native only to an era, not to a place, not to a culture.

Gilbert Munger: Quest for Distinction is a melancholy show, one that can be made sense of visually only when its subject is considered in light of the USPS’s chill fact. Development doesn’t figure in any understandable sense here, nor does progression nor vision. Munger makes sense chiefly as the charting of a restless, questing, but ungrounded sensibility.