Art Review: NRA, Now

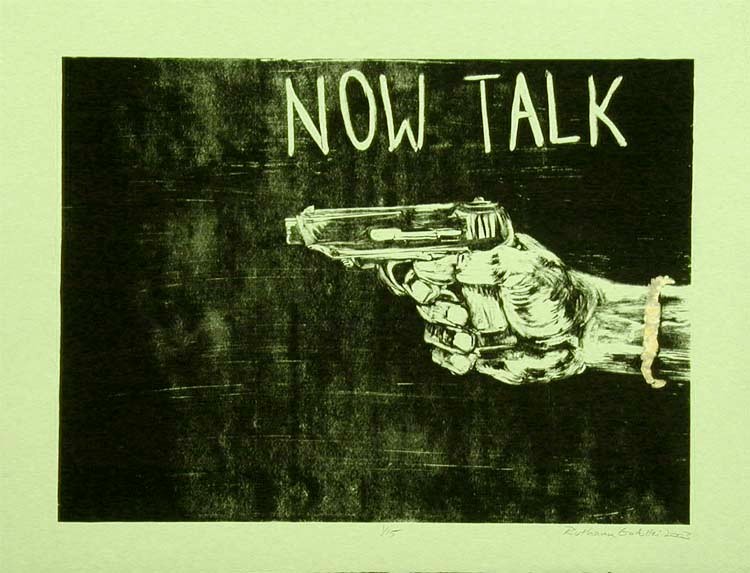

"Girls with Guns: Ten National Artists--A Portfolio of Prints" at Kellie Rae Theiss Gallery, portfolio organized by Jenny Schmid, show curated by Kevin Quandt. 400 1st Ave. N., Suite 318, the Wyman Building. Through August 30.

“The new revolutionaries might just have XX chromosomes!”

This tagline, one that could accompany the latest summer action movie, XX, is among the coy suggestions organizing “Girls With Guns” at the Kelly Rae Theiss gallery. In this portfolio of prints the woman with gun stands as a symbol of the empowered female. Jenny Schmid has organized the portfolio to include works by women and men; and as one should expect, identity politics are in broad evidence. Even though such politics can be humorless, that‚s not so here. The works are often funny, thought-provoking, and extremely well crafted, even if these ballistic broads are more Charlie’s Angels than SLA.

The prints are uniformly expert. The evocatively drab black-and-tan palette of one of Alexa Horochowski’s coloring-book blocky “Vaqueras” stands alongside the ornate Edward Gorey-like pastiche of Jenny Schmid’s “The Pathetic Death of Machismo.” The common symbols in these two works ˆ long-barreled guns, cowboy boots, and childlike women – set a whimsical tone. Here, carrying a gun is a part of dressing up: a tomboy accessory worn alongside cowboy boots, pit bull, and mini-truck: a violent taming of the macho. In Schmid’s “… Machismo”, a riot grrrl dominates an explicit gender dichotomy. At the print‚s edges, sperm-like cupids vomit flourishes of violence and reference, while at the center, our heroine takes aim at the titular demon with a rifle. The entire drama is colored in petal pink and baby blue. Yet, purging as such a reversal may be, it can also seem as slight as a pop song‚s kiss-off, or as empty as the digitally animated leather catsuits that kung fu fight in the summer’s action flicks.

Perhaps the simplicity of such pieces can be traced to the questions that stimulated this graphic debate. Asks the accompanying text, “If women were exclusively allowed to own guns in the U.S., would some political problems, such as domestic violence and school shootings, be solved?” To answer a question with a question: What meaningful debate can rest on the assumption, however tongue-in-cheek, that violence is a chromosomal deficiency? Instead of ending violence, from the sampling here we might conclude that women would like to turn their guns on men, thus solving the problem of power by reducing the sum to zero with a massive subtraction.

The prints become more thought-provoking when they ditch the sex-war paradigm for a specific cultural subject. In Valerie Wallace’s “Mr. & Mrs. Jack Sprat,” the famous fat-eater points her gun at her husband, who balances a bourbon bottle on his head, William Tell-style. His erect penis points back at her. Thus, the figures use their rods to point to each other in a senseless cycle of definition. You may find yourself silently incanting the nursery rhyme as you ride the elevator back to the ground floor of the Wyman building.

Lisa Bulawsky‚s “Young Mr. Heston” imagines the NRA president as a troubled child. He becomes a Munch-ian paranoid, clutching his face at the center of a maelstrom of guns, inverted fermata mammaries and fearsomely sexual women.

However ridiculed, the presence of Heston evokes a question that shatters the other works‚ glib facades. Who are these empowered women with guns if not the midnight parking lot vigilantes of gun lobbyist lore? Like political cartoons, many of these works seem as one-sided as they are colorful. When they use kitsch, as they often do, it seems not to challenge the simplicity of a gender face-off but to enforce it. The printing process seems to invite layering, of both meaning and medium, but in many of the works the cute patterned backgrounds that leak into the figures seem more fashion than substance.

In a gesture of fairness, Schmid has invited several male artists to join the debate, but if the women‚s work is violent fantasy, the men seem to evade the matter entirely. The true grit here comes from artists like Wallace and Bulawsky, who have refigured the theme, or from those who have worked outside of its rubric. In evidence, a second piece by Schmid stands outside the portfolio. “Fast Girl, Knocked Up” tempers its whimsy with angst and self-doubt. In what looks like a pivotal dream sequence from a lost graphic novel, the recumbent girl opens her legs, and the specters of past lays fly around the room with stoic possibility. They are harpies with long faces, invited wraiths with dull expressions, furies of bland indifference. Here, with gestation incomplete and possibilities left open, the viewer feels the invitation that is lacking in Schmid‚s other contribution, and perhaps in the conception of the portfolio as a whole. The replacement of muse with polemic has closed some of these works to imagination, but the works that evoke contemplation resonate beyond the confines of their context. Like Charlie‚s Angels 2, Girls with Guns isn‚t a cavalcade of masterpieces, but thanks to its more daring provocations, it transcends its blockbuster trappings to become one of the summer‚s must-see exhibits.