An Uneasy Trip: Budoff and Cristancho at the Duluth Art Institute

Suzanne Szucs reviews the work of Nathan Budoff and Raul Cristancho, "Round Trip - De Ida y Vuelta," at the DAI, 506 West Michigan Street in Duluth. Through Feb. 20.

Remembering is a tricky business. No matter our best intentions, we always get something a little wrong. Images of the past are sketchy at best. Dreams can seem more real than our memories. Taking a journey through another’s eyes is more difficult still: we are remembering through them, and it usually takes some major hand-holding if the experience is to be a full one. As artists we believe in a universal language, but differing cultures present barriers to understanding. When asking the viewer to make this journey, the artist needs to know his own expectations – how far does he ask the viewer to go?

In Round Trip – De Ida y Vuelta, their joint exhibition at the Duluth Art Institute, Nathan Budoff and Raul Cristancho ask the viewer to accompany them on a journey of remembrance not only of what was, but also for what might yet be. It is a disjunctive trip, requiring the viewer to forget herself and plunge into imagery or situations that might not be familiar. With this exhibition, Budoff, a North American painter residing in Puerto Rico, and Cristancho, a Columbian painter, represent to us the central and southern Americas. We must abandon U.S. chauvinism if we are to understand their meaning at all. This alone is a refreshing and generous reminder of how deeply other places and other peoples are affected by our society’s actions.

The exhibition presents work from each artist as well as collaborative pieces. A colorful, expressive palette holds the work together, although method and interest is clearly varied. Cristancho takes a more overt political approach and his work makes the bigger impression, although at times the resolution of the ideas feels a bit simplistic. Interested in the effect the United States has had on South America, he created Cuidad Kennedy: Memory and Reality, for which he collaborated with students, for whom he was project director. John F. Kennedy, who with his wife made a brief visit to Bogota in 1961, is conflated with a saint and Columbian ladies emulate Jacqueline Kennedy by modeling a Chanel-styled white suit, a reproduction of the one Jackie wore on her visit. The project is about the creation of myth and how it plays out in a community, the First Family representing the First World, but it is the photographs of the “Jackies” that allows it to take a more interesting bend. The suit is baggy and out of shape on the women, as it would never have been on the First Lady. These photographs reflect the nature of celebrity, image, and ownership. They ask, “Who belongs in this suit?” Clearly these women do not.

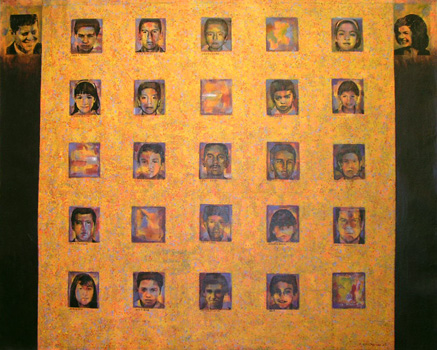

Johnes and Jaquelines carries forward this theme in a piece featuring portraits of children and adults who are namesakes of the mythologized visitors. Like the white suit, the names become the signifiers for inclusion, and Cristancho, through his choices, ironically validates the myth. Like a Warhol multiple, the faces are disposable commodities. They fade from our view into a colorful grid, reminiscent of “the forgotten,” giving the piece a double edge.

I really respond to Cristancho’s sense of color (he uses a lot of deep blues, purples, hints of greens and blacks, moody and atmospheric) and though at times his symbols are a bit didactic (a Western Hemisphere globe printed onto multiple hankies), there is a great deal of pleasure to be had in experiencing his stylized paintings. When he is using the simplicity of his elements well, like in Dawn, color suggests emotion, beautiful and disturbing.

Budoff’s paintings also use rich colors, but of a much more festive palette. Only his parrots are dour in muted greens, a reminder of their near extinction, reflecting the loss of southern cultures. His main subject is a brown/beige boy, mutated by loss and memory. At times Budoff’s painting feels flat, his push for symbolism heavy-handed. Boy with Ball featuring a zebra-skinned boy with one brown and one blue eye, is compelling to look at, but it speaks to racial division too directly.

On the other hand, Crossing, a simple image of the brown boy morphing into or out of a parrot, is the most compelling image here. Overall his paintings are centered, symmetrical, and realist; this one, though, is slightly off-center and the distorted features reach out to the viewer as if quietly asking for relief while demanding responsibility for the double extinction. The boy is haunting. Can we feel compassion for him or are we too repulsed? Is the parrot a burden, or does it magically free him? In its simplicity, the painting is opened up to more complicated interpretation and effectively communicates the discomfort with which the First World views the Third.

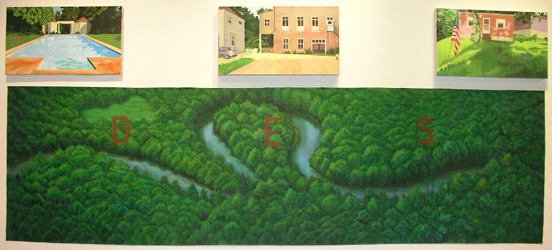

The work Budoff and Cristancho have done together is uncomfortable, perhaps fittingly so. Being more stimulated by Cristancho’s painting style, I am drawn to his contributions, especially in Doble Linea de Horizonte, where his large flattened landscape canvas overwhelms Budoff’s three smaller works. The trope of a man making a journey is recurrent in their shared work, but it is not the illegal immigrant we are used to hearing about. Rather, he is an equal disadvantaged by his condition. The journey to success, to understanding, seems long, hard, insurmountable. The suggestion seems clear – when will we, in dominating this hemisphere, look to the South and incorporate its lessons without lessoning its soul?

It is hard even writing about the Americas, so accustomed are we in this culture to refer to ourselves as American. How should I speak about those other Americans? Of course, this is the point and on the whole the exhibition is successful in compelling me to contemplate this journey of self-discovery. It might be nice to have a consistency in label translation to make it slightly more accessible to the average viewer, but most titles are relatively simple, anyhow. I don’t need them, but it is important to note that there are no solutions offered here, only memory and loss. Looking at it from a North American perspective, I am reminded that I have lots more work to do to qualify fully as an American.