American Dream? The Whitney Biennial

Michael Fallon writes on Minnesota artists in the Whitney Biennial (curated by the Walker's Philippe Vergne and the Whitney's Chrissy Iles). Click links at the article's foot for their conversation at the Walker, and for other reviews of the show.

Michael Fallon gives his take here on the current Whitney Biennial, which involved record numbers of Minnesota artists (depending on how you count, 7 to 9) and was co-curated by the Walker’s Philippe Vergne. Another take on it will follow in mid-May, from another of our roving correspondents.

The Biennial this year was particularly artist-centric; the curators selected artists to do works especially for the Biennial, and many of the artists did work that was quite different from any they had done before, delivering it in some cases only days before the show opened. So Vergne’s and Iles’s experience of the show was less curation than, say, orchestration–they were, perhaps one might say, impresarios loosely supervising a group of improvisors rather than curators assembling a collection of selected objects. This is reflected, of course, in the show; read on to see what it looked like to one observer. Click the links at the foot of the article to read more reviews of the show.

IN 1831, FRENCH ARISTOCRAT AND LAW COURT MEDIATOR Alexis de Tocqueville took a leave of absence from his job to travel to America, along with companion Gustave de Beaumont, a deputy public prosecutor, in order to study the American penal system. De Tocqueville and Beaumont’s book, Du systeme penitentiaire aux Etats-Unis et de son application en France, was published in 1833 and won the French Academy’s Montyon Prize. Still, De Tocqueville’s trip would be only a minor footnote in history had he not decided in 1834 to take on an even bigger subject, publishing in 1835 the first part of a two-part study called Democracy in America (the second volume appeared in 1840).

Opinions about the actual merits of Democracy are mixed, but something about the notion of an outsider trying to make sense of the burgeoning American experiment in democracy has persisted through the ages. Quotations from the book spring up in politician’s speeches; poli-sci and history students regularly have to labor through its prose, and imitators spring up now and then to offer a look at what’s going on in the Land of Liberty.

Two recent assessments of American culture reveal the difficulty of such analysis today. The first, by Bernard-Henri Lévy on assignment for the Atlantic Monthly in 2005, resulted in American Vertigo, a book that’s has been roundly panned, at least by American reviewers. The New York Times, for instance, said the book is “a disjointed collection of random observations, facile generalizations and MTV-style fast-cut takes on American popular culture,” and that the author, living “entirely inside his head,” does a poor job of actually looking out the window of his car and seeing the country.

I can also report that the second journey a la de Tocqueville—the 2006 Whitney Biennial—is as facile, disjointed, self-indulgent, and preoccupied as Lévy’s book.

THE WHITNEY MUSEUM OF ART announced more than a year ago that the two curators of its signature Biennial exhibition, Chrissie Iles and Philippe Vergne, were the first European team to curate the show (which they titled “Day for Night,” after a Truffaut film originally titled Nuit Americaine, which referred to the Hollywood film technique of shooting night scenes in daylight with special filters), promising something different for the big event. Speculation focused on what the Europeans would choose to showcase in this markedly American exhibition, and preliminary interviews revealed the particular preoccupations of the curators. “Through the curatorial lens of the Biennial,” said curator Chrissie Iles at one point, “‘Day for Night’ explores the artifice of American culture in what could be described as a pre-Enlightenment moment, in which culture is preoccupied with the irrational, the religious, the dark, the erotic, and the violent, filtered through a sense of flawed beauty.”

That is, the curators had an axe to grind, and they were going to take their finely honed blade to the culture that surrounded them—searching out a slate of artists who would give vent to a wide range of complaint, grievance, and absurdity about America.

To some degree the Biennial is always a big slab of axe-hacked meatloaf, with little conceptual shape, form, or readily discernible taste—after all, what else can one expect of a show with upwards of 100 artists? But this time the curators might just as well have hung a bunch of sausages on the Whitney’s walls—the art in this show is just so much processed meat. It is such a mishmash of young Turk artists howling and shouting in the wilderness to get noticed, that the show amounts to a whole lotta slaugherhouse waste.

OK, I exaggerate, but this show is definitely a tedious mishmash of artists who probably shouldn’t be here. Consider the first artist I came across—an artist I’ve met, when we both lived back in Minnesota—Jay Heikes. His work is tucked away in a corner gallery up on the fourth floor (the topmost of the three floors of the Biennial), but I have a habit of traversing these big shows from the top down. I do this is because the top floors are usually the quietest, and I like to save the big-money stuff, the over-the-top stuff that the shows start with, for last. This time, it was probably a mistake.

As for Heikes, I should admit I’ve always been on the fence about his work. In an earlier review, I called him an aging “high school doodler” and said he “draws with the inveterate compulsion of the high school wallflower.” Still, for the Biennial I thought he’d clean up his act a bit, perhaps bring just a tad of craft and grace into his sly, winking, pop-culture-sopped scribbles, and maybe make something that actually took into account the needs of the viewers’ eyes. But alas, I am sorry to report, in many ways he’s gotten even sloppier and more distant. His image here is a wall of large-format photocopy paper thumbtacked up. On this mural surface, Heikes has done his trademark careless scribbling, including slogans and crude images, such as a middle finger (Is this to the audience?). The subject of the piece is vaguely associated with its title, “So There’s This Pirate…,” explaining the presence of a parrot on one sheet (though not the flipping bird). Apparently, the serial images come from a video of the artist himself telling a joke, though why anyone except the artist should care is never explained.

Can you tell I was disappointed with Heikes’ showing? Many of the hundreds of works bugged me and a few (very few) intrigued me, but I had a similar reaction of disgust and disappointment to another Minnesota artist in this show, Todd Norsten. His work was stuck in the morass of the bottom-most floor of the show, amid a massive slew of trying and familiar complaints about the state of the world and everything in it.

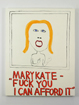

Norsten’s three paintings are terribly poor efforts. He seems to have regressed. Past paintings were clever and well-crafted objects, sometimes abstract swirls, sometimes fabricated sculptural canvas-objects; now, his work references the same pop-cultural crud that obsesses Heikes. Norsten paints Mickey Mouse (come on!) and Mary-Kate Olsen (!) in faux-naïve, crude style, with sloppy words (again, with the scribbles! What is this, the 80s?). And, to boot, Mary-Kate is, for no apparent reason, telling the viewer to fuck off (in both gesture and finger).

What is it with these two artists, flipping off the very audience who’s come to see their work? There are two works that include the words “Eat Shit and Die,” which has to be some sort of a first in a major American museum. I’ve been contemplating starting a petition that the show’s title be changed to the more apropos “Eat Shit and Die (America).”

Norsten’s floor, the last I came to in this show, is a quagmire of complaints, trite political commentary, and endless callow anger directed at the converted. What’s perhaps so maddening about this, other than the fact that it does not make for very good art, is that all this accusation, political gesturing, and pointless shrillness may have various intentions—purging inner demons, helping to cope with frustrations about the world/times, maybe even to create change in the world—but its ultimate effect is to drive away the viewers, those very people most sympathetic to the artists’ subjects and causes.

My friend Katy, for instance, halfway through the second floor simply gave up, saying she couldn’t take it anymore. She left. I tarried onward but I could see her point. Aside from being flipped off twice and told to eat feces before I expire, I was reminded how unfair life in this country is to the various categories of all of us: people of color, people of alternative sexual orientations, to the poor, to everyone in all their groupings. I was reminded how we are exploiting and ruining our earth. I was told that war is bad. I was given glimpses into numerous disturbed minds, fed up with the perceived direction of the culture. I was worn down and ground down by artists who had no concern for the well-being of a viewer, only for their obsessive passions or angst. None of this was told to me with even the slightest of cleverness. And there were few moments of grace, quietude, craft, or beauty in all of this bile.

What I ended up thinking at the end of all this was, what were the curators after anyway? What sort of political point were they trying to make with such (often) terribly awful art? They seem to have abdicated their responsibility, as curators of arguably the premiere showcase of art in America, to act as gatekeepers, to have some standards for art beyond the personal axes to grind, and to keep the bar high—for the sake of the immediate viewer, who may become nauseated and leave, but also for the sake of the future, the idea of what art is for.

There have been numerous commentators in recent years who have suggested changes to the Whitney Biennial’s format. In particular, critic Tyler Green in a recent column suggested the show should focus on 7 or 8 key artists who really represent the best of what’s happening at the moment, giving us a chance to digest their work and have a meaningful experience. There is some merit in this idea, I think. For instance, I found myself wanting to see more of Minnesota photographer Angela Strassheim’s work, a rare bolt of clarity and craft in the midst of the stream of sewage. Michael Kimmelman, in the New York Times, called her images “surreal pictures, candy colored and strangely loving.” They are odd and beautiful images of emotionally vague family interactions, eerily lit in a cold, plastic light (Strassheim is a forensic photographer). They leave you wanting to see more.