Allen Ginsberg and the Quiet Librarian

Terrence Williams, a volunteer tour guide at the Walker Art Center, remembers his lifelong friendship with the legendary Beat poet in a conversation with writer Courtney Gerber.

IN HIS EIGHTIES, TERRENCE WILLIAMS IS CASUALLY DAPPER in a tweed sports coat, pressed jeans, horn-rimmed glasses, and New Balance sneakers. One can often find him at the Walker Art Center, where he’s a volunteer tour guide and dedicated patron. I’ve always known Williams to exhibit a gentle, unassuming demeanor; it was only after a recent conversation with him that I began to appreciate the extraordinary color of his life: He once dated a six-foot tall Icelandic woman who smoked cigars; he housed the peace-activist folk-rock band The Fugs for a couple of days in the 1960s. And he counted Allen Ginsberg among his friends, remembering the poet as a man he knew to be “genuinely humble and kind and generous” — words one might also use to characterize Williams himself.

I learned of his history with Ginsberg shortly before last month’s Minnesota premiere of Howl, a new film by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, starring James Franco as the young Ginsberg. Before he retired, Williams was a librarian by profession, and his passion for words and stories has remained a constant in his life. He currently lives in St. Paul with his wife, writer Patricia Hampl, but as a young man in the late 1950s, he was an apprentice to an antiquarian bookseller in Palo Alto, California, just a stone’s throw from San Francisco. At the time, Williams and his then wife Nancy were immersed in “the incredible fog/sunshine morning light of San Francisco and the museums and the jazz clubs.” Williams recalls his first real Italian coffee at the Caffe Trieste, browsing the shelves at City Lights. He also remembers reading Ginsberg’s Howl and following the coverage of the subsequent obscenity trial that surrounded its publication.

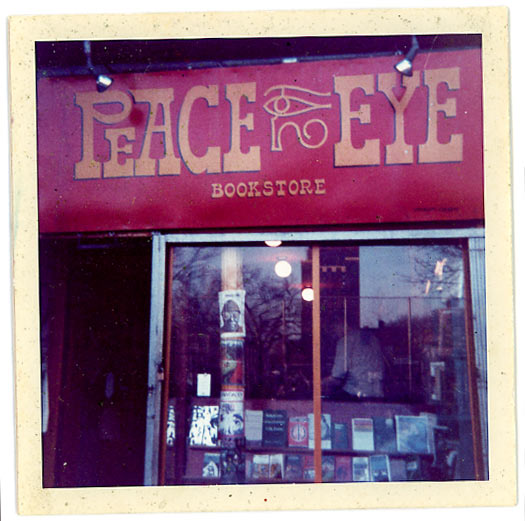

By the mid-1960s, Williams had moved on from California to reside in Lawrence, Kansas, where he spent his days at the University of Kansas library, working on a grant to purchase literary ephemera for the collection. He reflects, “One of the best resources available to me for this material was the Peace Eye Bookstore in New York, where Edward Sanders was the proprietor. His [book] catalogs were fantastic works of art, as well as being guides to what was happening in the new poetry in New York.”

It was Sanders who introduced Williams to Ginsberg; the bookstore owner asked if Williams would host the poet, who was traveling across the country as a Guggenheim Fellow, and set up a reading for him at the University of Kansas.

I chatted with Williams about that first meeting with Ginsberg, and his impressions of the man who would become his life-long friend. Below are excerpts from our conversation.

Would you describe Allen Ginsberg’s first visit to Kansas? What was it like to hear him read his poetry in person?

One fine day in early spring, Allen and Peter Orlovsky [a writer and Ginsberg’s partner], and the photographer Robert Frank and his girlfriend showed up at our house on Missouri Street in Lawrence. Peter’s brother, Julius, who was catatonic was also part of the group at this time. Allen [Ginsberg] had bought a VW bus, and they were driving around the country learning about America. Bob Dylan had given him an Uher tape recorder about the size of a portable typewriter. He would speak his observations and his thoughts into the tape recorder as Peter drove them around the countryside. Then, at night, he would transcribe and edit whatever he felt worked. At the time he was writing Wichita Vortex Sutra.

______________________________________________________

I was living that uptight Mad Men mentality, and Ginsberg came through for people like me — with his courage about just who he was, with his dangerous, wide-ranging literary intelligence, with his muscular idealism.

______________________________________________________

This motley crew all slept in the attic of our house. Another contingent arrived a day or two later: Barry Farrell, who was writing a piece called “The Guru Comes to Kansas” (Life magazine, May 27, 1966), and his cameraman; also on board were poet Charlie Plymell and his wife Pamela. These houseguests were all wonderful and exciting.

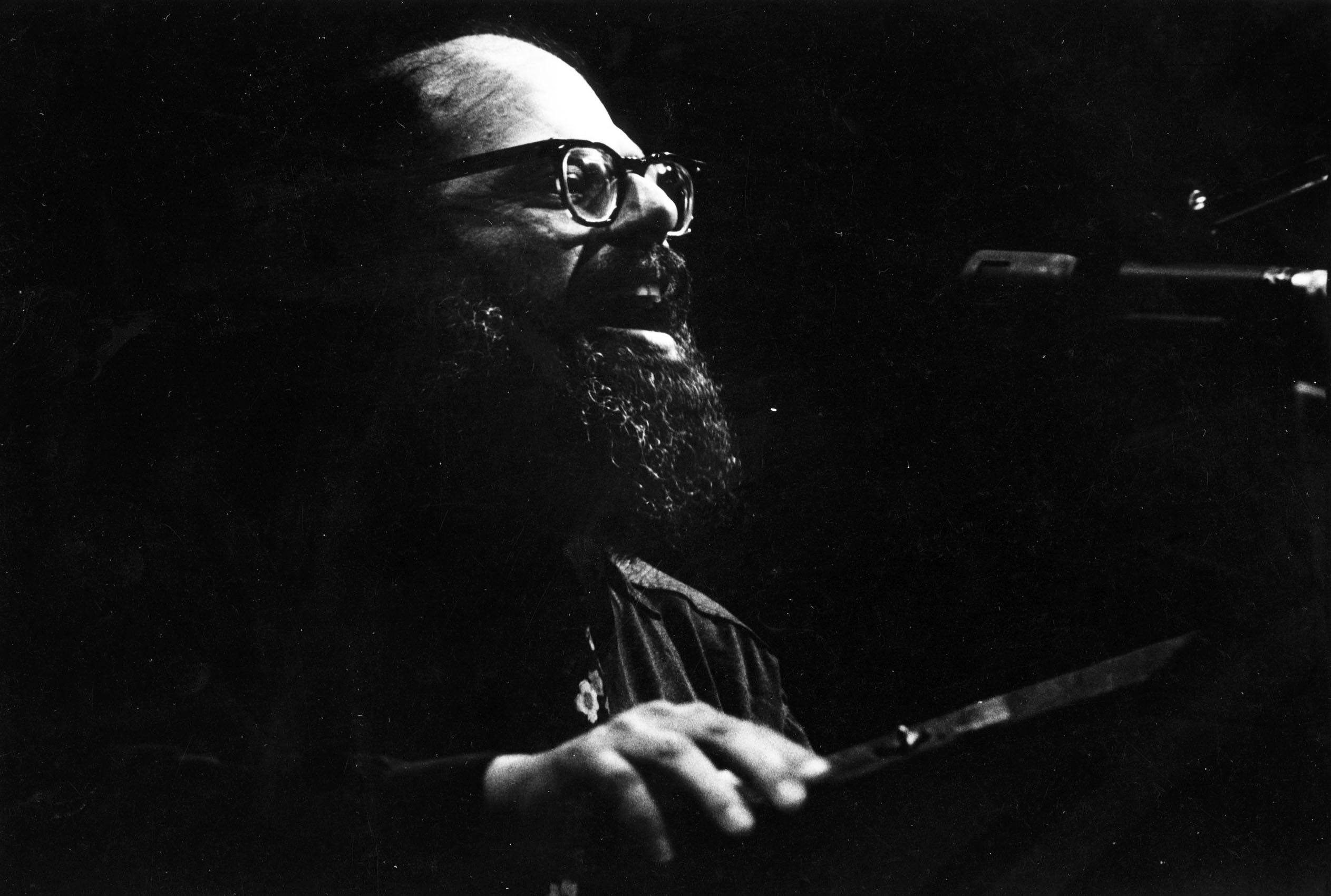

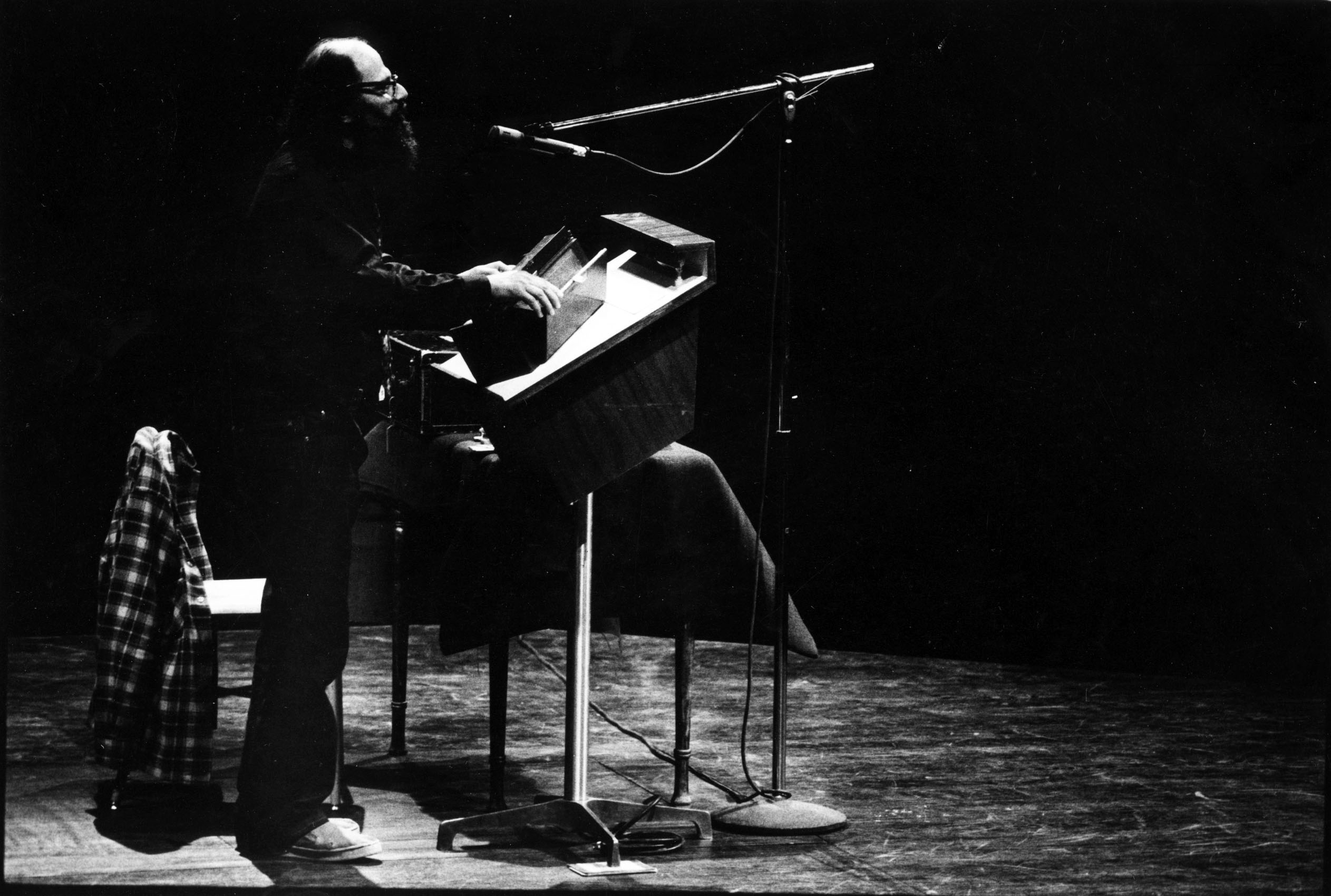

I had organized a reading for Allen, sponsored by the University of Kansas libraries, at the Student Union in the spring of 1966. The whole building was overflowing with people on that afternoon. William Burroughs was there, too. I was petrified because I knew how sharp and shocking Allen could be, and Kansas was still … well, Kansas. Things were pretty buttoned-up. He stood at a podium on a platform, in the guru costume — the long beard, Peter seated beside him on an oriental rug with a tambura drone on his lap. The two of them played and sang for an hour-and-a-half to an audience that was mesmerized, really swept away by the power and the beauty of the language — the rhythms, the message of peace and love. He was messianic … We were told that the University of Kansas was a different place after that reading.

What are some of your lasting memories of Ginsberg?

I was living that uptight Mad Men mentality, in the stiff regimentation of an academic community, where everyone was always vaguely worried about our Mexican standoff with Russia. Ginsberg came through for people like me: with his courage about just who he was; with his dangerous, wide-ranging literary intelligence; with his muscular idealism. His example influenced me and changed my life.

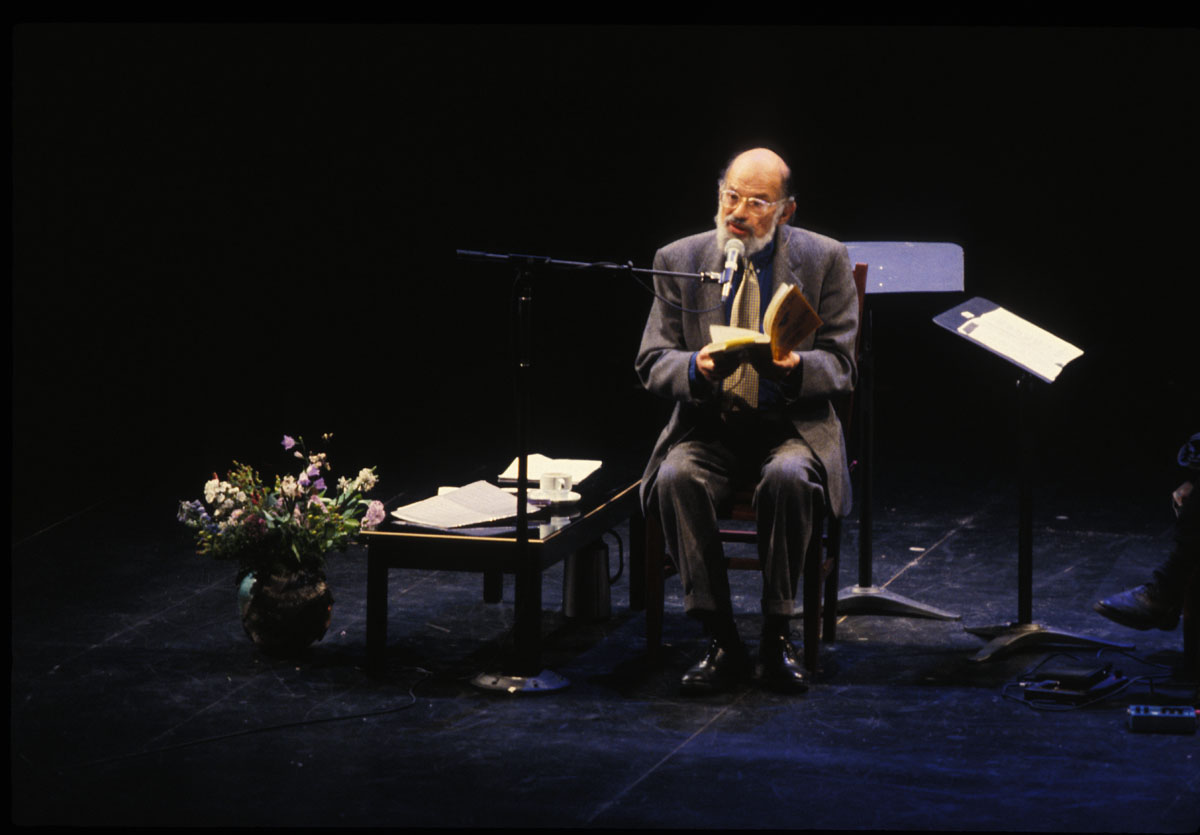

In reflecting upon the later visits he and Hampl paid to Ginsberg in New York in the 1980s, Williams recalls the poet “washing his socks by hand and putting them on the heat register to dry. Shelving his books in apple crates in his Lower East Side apartment, even as an older man and, by then, very famous. He lived like a graduate student. At the same time he was absolutely confident about his art — flamboyant. He wrote and spoke spontaneously, forcefully, brilliantly.”

As we closed our conversation, Williams reminisced about the visits Ginsberg made in his later years to Williams’ and Hampl’s home in St. Paul. He then brought his thoughts to the present, with this observation:

[Ginsberg’s] manner of fusing prayer and political strategy seem evergreen for today’s problems, though he used them in and for a different era and different world tensions … I can see him and Peter Orlovsky, sitting by the proposed Islamic cultural center in lower New York chanting — om om om — to the upset crowds there, calming their fears. He might have done the same thing earlier on the steps of the New York Stock Exchange. We could really use him now.

When I think over our chat, I imagine Williams savoring the final line of Ginsberg’s Footnote to Howl: “Holy the supernatural extra brilliant intelligent kindness of the soul!” It’s a rousing finish to the poem that gave a voice to the contradictory nature of the people and milieu of 1950s America: simple and outrageous, angry and peaceful, defeated and hopeful. Ginsberg’s cry is baldly stated but empathetic. Ginsberg, along with writers like Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs, infused literature with a new sense of urgency to close the gap between art and everyday life. They aimed to recognize the cultural relevance of the quotidian — something their brothers and sisters in the visual and performing arts were also keen to do.

______________________________________________________

Related events:

Find out more about HOWL, a new film about Allen Ginsberg’s poem and the poet’s subsequent legal battles, on the official website for the movie.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Courtney Gerber directs tour programs at the Walker Art Center and is a writer based in Minneapolis.