A Variety of Women (Who All Happen to Be Immigrants)

Alex Starace points out that you dont get exactly what youre promised at the Immigrant Status: Faith in Women show at the Intermedia Arts building.

As you enter the Intermedia Arts building and pick up a brochure for the show “Immigrant Status: Faith in Women,” you’ll find the following description: “[this exhibition] looks at matriarchal societies and questions gender differences as they relate to faith and its many definitions.” It’s a garbled and vague description of the goals of the show, goals that are not so much impressive as they are broad and unspecific. Such outsized and naive idealism is found throughout the exhibition’s literature – a wall didactic claims the show “offers an opportunity to talk about what ‘faith’ means at a time when individual beliefs have become American fodder for power and terrorism,” and then goes on to insist that the show is about women, the joining of cultures, tradition and modernity, newness and hope and – the wall didactic continues – it’s all viewed through the lens of ‘faith’ – a term that’s so nebulous and undefined that the curators felt the need to place it within quotation marks.

That the show achieves almost none of this teary-eyed pap is unsurprising. Nor, then, is it particularly surprising that the exhibit ends up being little more than a series of rooms, each displaying the work of one or two artists who happen to be female immigrants: about half the pieces have a clear relation to religion, but about half don’t; about half the artists are quite talented, about half aren’t; about half of the pieces are examples of crafts, about half are paintings. All told, it’s a hodgepodge – a fairly enjoyable hodgepodge – of art that can’t all accurately be described under one overarching and coherent thesis.

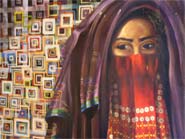

That said, if the ostensible purpose of the exhibition is to explore the intersection of immigration, womanhood, and faith, there is one artist – Heba Amin – who clearly does just this. In a series of untitled works, she uses ink (possibly a pen) to draw the outlines of groupings of women wearing what appear to be hijabs. Aside from these outlines, most of the rest of the canvas is blank – completely unpainted upon – and has an evocative sparseness reminiscent of traditional Japanese scrolls. But, in each canvas there’s also a square (5” by 5” approximately) of abstract watercolor that is best described as having the same blurry and colorful pattern that you find when looking out a rain-covered windshield. The result is a contradiction: the tradition of the blankness and the hijab versus the modernity of speed and color. The women in the works seem caught in both, uncertain where to proceed, but certain that, within their hijabs, they will encounter the rush of modern life.

Another notable work is that of Patricia Mendoza, whose room-filling installation Te voy a contar un cuento is hidden behind a curtained doorway. Once inside, there’s a colorful wash that features graves, castle towers, skeletons, butterflies, and floating hearts, along with, on the far wall, a collage made up of various magazine clippings of scantily clad women, many of which are taken from Victoria’s Secret catalogs. Dangling from the ceiling is an enormous “caleidoscopio de la vida,” inside of which are reflected (and refracted) the colors and body parts of the installation. Matching the kaleidoscope for dramatic effect is a large vaginal sculpture made out of fur and cloth. Inside the vaginal opening sits a magazine clipping, this time of a blue-faced and calm-looking indigenous woman. Finally, and somewhat less impressive, there’s a video showing various older women talking as though giving an interview for a documentary.

The initial effect of being inside a room that incorporates such a barrage of media is pleasantly overwhelming and it takes a minute to puzzle together the story of the installation – it’s in this moment of exploration, during which the viewer is mildly confused and surprised, that Te voy a contar un cuento is most effective: it has done the job of an installation – it has transported the viewer to another world entirely. Unfortunately, once the viewer figures out the world of Te voy a contar un cuento, the installation is less impressive. It, like the title suggests, is a straightforward narrative, in this case a story of the ills of the cult of beauty.

Writing along the walls helps the viewer puzzle it out: there’s a great grand world out there and women’s bodies are inherently beautiful, but most women (especially young women) waste all their time worrying about superficial appearances when in fact that’s not at all what’s important in life: the truest, strongest, wisest, most beautiful women – the ones who are true heroes – are the older women talking on the video projection. It turns out to be a standard denunciation of superficiality and affirmation of innate female wisdom using the usual motifs: images of barely-clothed hotties to allure and mislead, an overlarge vaginal image to shock and confront, a depiction of the possibilities (and tragedies) of the world outside the cult of beauty, and finally the strong women who know how to use their intellect and who have therefore reached some level of self-actualization.

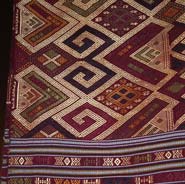

What is strange, then, is that the work of Bounxou Chanthraphone and Laddavanh Insixiegmay is displayed in the same exhibition. Each artist makes crafts – that vast category of artwork that the traditional patriarchy has haughtily sanctioned for the second-sex – exactly the sort of endeavor that Mendoza’s Te voy a contar un cuento would seem suspicious of. But no matter – Chanthraphone and Insixiegmay are clearly very talented artists. Chanthraphone makes tapestries out of pure silk, using the mut-mee process, the highlight being an extremely large white-and-gray rendering of Angor Wat.

Insixiegmay (Chanthraphone’s daughter, incidentally) does traditional Lao soap carving. She makes flowers out of bars of soap and then buys fake stems and leaves, gets a flower pot and dirt, and assembles everything to create an extremely life-like imitation of specific flora, such as in her works Yellow Bell Tulips, White Wild Roses, and Hope Roses. The effect is uncanny. Not only do the fake flowers smell like flowers (the soap is scented) but they’re life-like enough that one gets to reconsider the flower as a source of beauty: while inspecting a false version one is prone to analyze the subtle curve of tulip petals and the bulbous and layered shape of half-bloomed of roses – in this case, the artificiality gives just enough defamiliarization that the flower-lover is able to appreciate flowers anew.

But perhaps the most impressive work is that of Emily Villaseñor, whose paintings can be found in the cafe. Her piece Queen of Hearts shows a very masculine-looking woman wearing a crown and hoop earrings and having either a shadow or a mustache over her upper lip. In both Revolutionary 5 and Revolutionary 7, a man with feminine features (or a woman with slightly masculine features) wears a Pancho-Villa-type outfit, complete with an ammunition belt. In all three works the subjects are nearly androgynous and look neither happy or nor unhappy, but distant, perplexed. Each, because he or she is clothed in the garb of rebellion or power, is supposed to exude a certain overt sexuality associated with his or her particular costume. That the androgynous figures cannot and will not do this makes for an unsettling, if poignant image: Is control about appearances and pretenses? Is it really so strange for a non-masculine person to wear an ammunition belt? Where are the enthusiastic, power-hungry expressions on the faces of the figures? It seems that, by wearing such costumes, the figures are out of place, but, because they are labeled as queens and revolutionaries, they’re not out of place – they are queens and revolutionaries. In the end, it’s the viewers with the problem – perhaps queens and revolutionaries aren’t always as we assume them to be.

Equally impressive is Brownie, in which a short-haired woman who’s not wearing any make-up looks distractedly off canvas. The string of a helium balloon touches her right shoulder, but the string leads, instead of to a balloon, to a floating female head that has dainty mascara, a perm, and pouty lips. Such a distant and inescapable daydream, the product of a beauty-obsessed culture, is made more evocative by Villaseñor’s Rothkoesque use of pastel colors: Brownie has as a background a wash of light baby-blue on top of which hovers a box of pure pink and a box of pure peach, highlighting the distance of the figure’s reveries as well as Villaseñor’s ability to incorporate abstraction and color into a representative work. She, much more than any other artist in the show, is able to meld complex ideas, technical virtuosity, representation, and pure visual beauty into one piece of art.

Villaseñor’s skill makes the fact she’s exhibited in the “Faith in Women” show, a show which has literature filled with obtuse moral questions and condescending pats on the back, mildly frustrating. The exhibition literature includes phrases such as “How do women preserve hope and bring their culture to their new surroundings when challenges of the new and old clash?” and “We honor these strong women and their art. They are expressive, bold and invaluably woven in the fabric we call ‘Minnesota.’” Such expressions are not only hopelessly general and maudlin, but also obscure the achievements of the art in the show; to assume (as it seems that the curators do) that the display of art is innately important (and never describe what exactly is so important about it) and to pretend that if the general mass of people are exposed to cultural art they will somehow become more sensitive and open to cultural understanding . . . well, it’s a pretty simplistic idea and one that presents the “Faith in Women” show as an easy target for philistines. Furthermore, such a notion causes the curators to gloss over the differences and specificities of the actual art in the exhibition, meaning that in the end it’s quite to the artists’ credit that much of their work is able to transcend such bumbling.