A Supple Mind

Lightsey Darst digs into the intimate, occasionally contradictory relationship that emerges when a dancer brings new choreography to life. Case in point: the mercurial artistry of Zenon's Leslie O'Neill and STORM, a new commission by Daniel Charon.

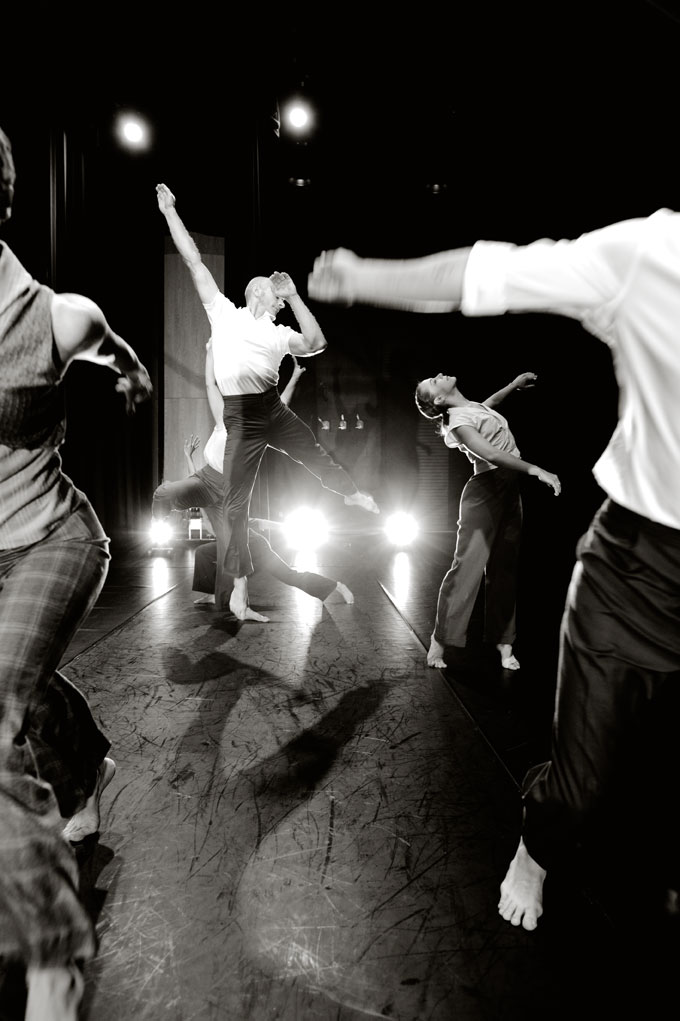

I’M WATCHING ZENON DANCE COMPANY REHEARSE DANIEL CHARON‘S STORM, and my eye keeps going to Leslie O’Neill. It’s not the first time I’ve noticed how her supple, powerful flow moves up from the floor to her pelvis like oil drawn up a wick by flame. Like everyone at Zenon, O’Neill attacks without throwing her energy away, but in the last few years she’s learned to make that reserve dangerous — a woman luxuriating on the verge. No wonder she’s been awarded a 2010 McKnight Fellowship (look for her in next year’s McKnight solos concert); no wonder people are talking about her.

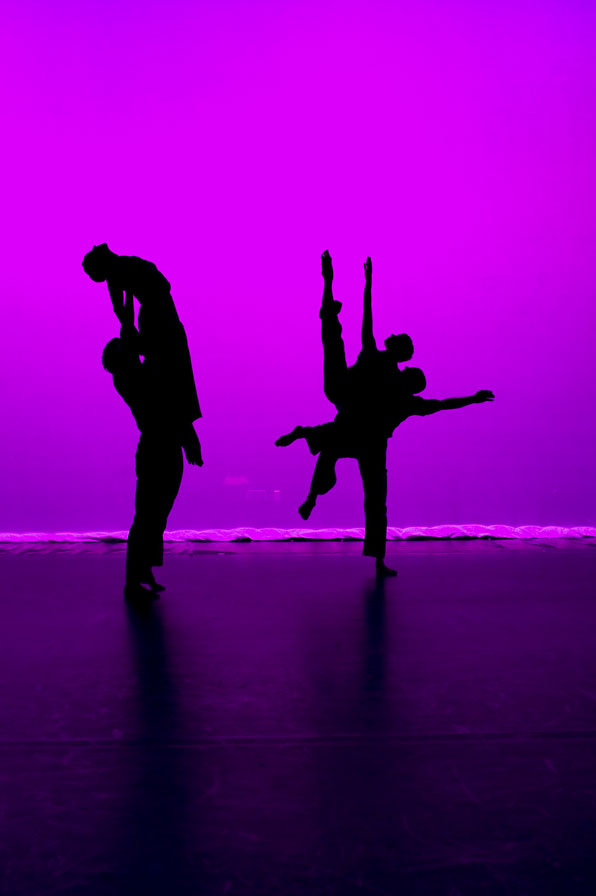

Today, though, I’m drawn to her because she has a problem. Early in Storm, O’Neill has a sensuous repeating phrase — a flip, split, roll on the floor — she executes often gazing at another dancer, as if she wants to touch but can’t reach beyond herself, can’t give up the need to make herself understood. This phrase sets the tone for the dance’s foreboding and tumultuous first section; O’Neill is the allowing spirit for impending chaos, her restless energy inviting it in, and the other dancers swirl around her. In particular, Laura Selle Virtucio gets caught in her orbit, and the two collide, tussle, and part, over and over again, O’Neill pushing at her partner or shying from her in a no that echoes across the stage. In the second and into the third sections of the dance, without being obviously featured, O’Neill still leads. When she makes a decision, the mood changes; her difficulty and desire are the dance’s drama.

But then in the fourth section the yes Selle Virtucio’s been pushing against O’Neill’s no takes over, and it’s golden Laura rather than dark Leslie who leads the last ecstatic dance, a charge toward the front of the stage that repeats, wavelike, as each other dancer joins in. O’Neill is the last to join, and she has no transition time; she last went off striving, still struggling through her own resistance, and now here she is smiling, her arc unfinished.

When Zenon performed the first and fourth sections of Storm at the Cowles opening gala, people noticed the abrupt mood shift, but I at least thought the full dance might resolve it. Now that I’m watching the whole thing, though, the problem is worse. O’Neill’s centrality and her frustrated progress make the ending feel facile — not a celebration, but Zenon slipping into celebratory mode as if into a smile for company.

The Monday before opening night, when I talk to O’Neill, the gap’s on her mind. “I don’t have the same resolve everyone else gets,” she says. Selle Virtucio’s moved on, but “I’m still trying to tell her something. I can’t let it go. Everyone else is able to calm themselves but I can’t do it. It’s powerful when I can, but I don’t feel like emotionally I’ve gotten there yet.” Then, switching tacks, she declares, “Don’t get me wrong — I can do that authentically, but only because I’m Leslie and I’m glad” that the piece is almost over, that she’s “not injured and still dancing with all of my favorite people” — in other words, only by breaking herself into two personalities.

She’s not sure how the gap arose. She doesn’t think that Charon intended for her to have a central role, and perhaps he didn’t notice her course through the piece. As is typical of Zenon’s out-of-town choreographers, Charon was here only briefly to create the piece; since then, aside from a brief visit to polish the first and fourth sections for the Cowles gala, the dancers have had to try to hold the piece together on their own — not just to remember the steps but their inflection and intention as well. In this process, things often shift a bit, and now O’Neill fears that she’s caused this problem with her own interpretation, that “maybe I’m making it all up.”

In conversation, she starts at zen calm, charges out in one direction or another, then backtracks and charges again. She contradicts herself such that once I have to read her own words back to her, but her contradictions mostly have to do with herself. It seems that what Leslie is in a given dance is a fraught question, all the more so because what she really values in her fellow Zenon dancers is their ability to be themselves at all times. “That’s where the magic is — they know themselves so well.” Regarding Storm, she tells me “I was deathly afraid of tornados” when she was a girl. But when I ask whether this dance, then, has special meaning for her, she answers, “No, it doesn’t feel personal.”

So, what does she think will happen with Storm on stage? She talks about how “a lot of things fly out the window” in performance. She might fixate on one moment, only to realize suddenly that what really matters is one step over. Are these missed opportunities? No, because if she’s had the realization, “I still got there in time. I’d rather realize something with the audience there.”

I ask her about her fears for the concert. “I’m afraid I’ll look very, very tired, that I won’t be able to hide my”… she pauses — “suffering.” She smiles.

There’s a lot going on under that smile.

______________________________________________________

O’Neill is that rare dancer who can turn thought visceral and sensual. Everyone’s been talking about how supple her body is, but what’s suddenly clear to me is that her mind is even more so.

______________________________________________________

SATURDAY NIGHT AT THE CONCERT, I’m as nervous as if it were me up there. I feel like no one around me knows what’s going on: If O’Neill doesn’t find her own way through Storm, the piece won’t be a disaster; it’ll just ring a little false, and no one will know why. But then, if O’Neill can do it, again, no one will know what she’s done or realize her critical role.

The show begins; she flies out of the wings. Already I can tell something’s changed, and it’s tiny, her breastbone just that inch more open. I’m oddly disappointed in myself: Why did it matter so much to me that she make that minute shift? Then I realize I’m asking the wrong question. The question is, how did O’Neill make it matter so much to me?

I go on watching. She’s receiving partnering differently this time, I notice, yielding, receiving. She’s become younger; when she attacks, she does it instinctually, without knowledge. She’s made room to find something out.

As we come through the third section and into the fourth, though, I start to worry. There’s so little for her to make a difference with. And as everyone starts in behind Selle Virtucio, I wonder whether O’Neill can do this last step like herself (whatever self she is now). She walks out and, unlike in rehearsal, her arrival seems pivotal. There’s no question the moment belongs to Selle Virtucio, but when on the last pass O’Neill finally breaks into a smile, she doesn’t simply fall into line: her dark abandon completes Selle Virtucio’s golden ecstasy.

The same evening, after the performance, I sit down with O’Neill to find out what happened for her, how it went. At first I’m a little disappointed that she seems barely to remember what we talked about: “Really all I need to do is broaden my scope a little,” she says, to solve the gap. But when she starts to talk about it in detail, I see that she’s had a change in focus, from one single problem to a field of free play. “It’s the really little things” that matter, she says. “I saw [Laura] slip on some sweat on the floor and it made me concerned for her in reality. . . when I finally went to the floor [at the end of their duet], I felt closer to her — she and I just went through a scary moment together on stage.” She goes on:

Who knows what tomorrow will be? When I hit the floor, am I going to want to keep watching her {Laura]? Am I going to want to just gather my thoughts for a minute and be closed off? Or am I immediately going to see Greg and Tamara coming in and filling the space with this lightness. . . The choices I have — none of them are wrong.

When I ask for more specifics, she talks about Storm‘s last phrase: “I get to do that three times.” As she comes out on stage, “I’m feeling like I have to change.” Then, “I’m waiting to feel how the movement feels to me to tell me how to respond” — letting herself learn the emotion. “I get three times to work up to it” — up to the height of Selle Virtucio and the others.

But this is a change. Before, she told me she needed to come out of the wings radiating joy all the way to the seats in the back of the balcony, that this was what her choreographer and director wanted. Where did you get the authority to make this change? I ask her. “I didn’t get the authority,” she says, her voice low, a little sheepish, but excited. “No one told me I could do that.”

O’Neill says this free choice isn’t usual for her. She talks about how some dancers “will just take those freedoms,” while she’s usually a stickler for original intent. But by now I suspect that O’Neill’s dancing owes its iridescence to her flickering mind, that her innate contradictions are actually a way of moving. She admits that changing her mind can be “a way to find some more freedom.” Yet she’s not being elusive merely for its own sake: “I can see all sides. Lots of things are true for me at any given moment.”

Some dancers are all personality and emotion; for them everything is a personal drama. Some dancers work from intellect, from curiosity, argument, or experiment. O’Neill is the rare dancer who can make the latter approach as vivid and moving as the former, who can turn thought visceral and sensual. Everyone’s been talking about how supple her body is, but what’s suddenly clear to me is that her mind is even more so. And not only that: O’Neill is just beginning to let herself see her own power.

Curious, I ask what O’Neill would have become if she weren’t a dancer. “A meteorologist,” she says promptly. No more fear of tornados: “I love weather.” Look out when the dancer who loves weather learns how to make her own.

______________________________________________________

Related performance details:

Remaining shows for Zenon Dance Company’s fall concert are November 25, 26 & 27 at the Cowles Center for Dance and the Performing Arts in Minneapolis. Ticket information available online here.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She hosts the writing salon, “The Works.”