A Poet’s Pilgrimage to Cold Mountain

Britt Aamodt profiles the documentary, "Cold Mountain: Han Shan," by filmmakers Mike Hazard and Deb Wallwork and poet Jim Lenfestey. The story is at once personal and historic, about kinship that crosses centuries and one man's quest to honor his muse

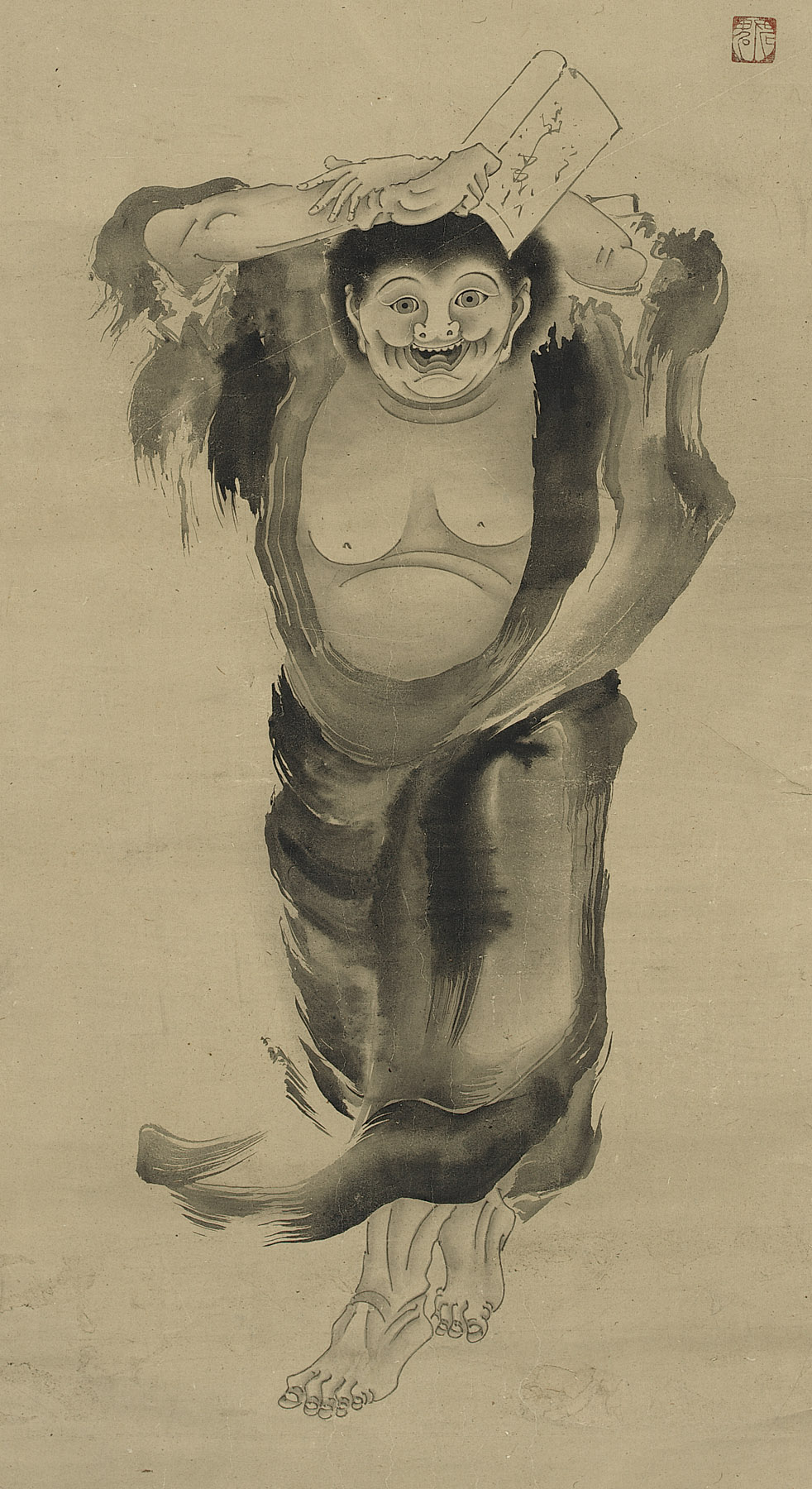

Once upon a time, over a thousand years ago in Tang Dynasty China, a scholar, bureaucrat, husband, and father abandoned the “dusty world” for the fog-wreathed Tien Tai Mountains. He took a cave for his home and begged for his daily bread at a monastery there. He carved poems on trees outside the mouth of his cave and painted verse on the rocks. The poet eventually assumed the name of the mountain where he dwelled; it was called Han Shan, or “Cold Mountain,” and so was he.

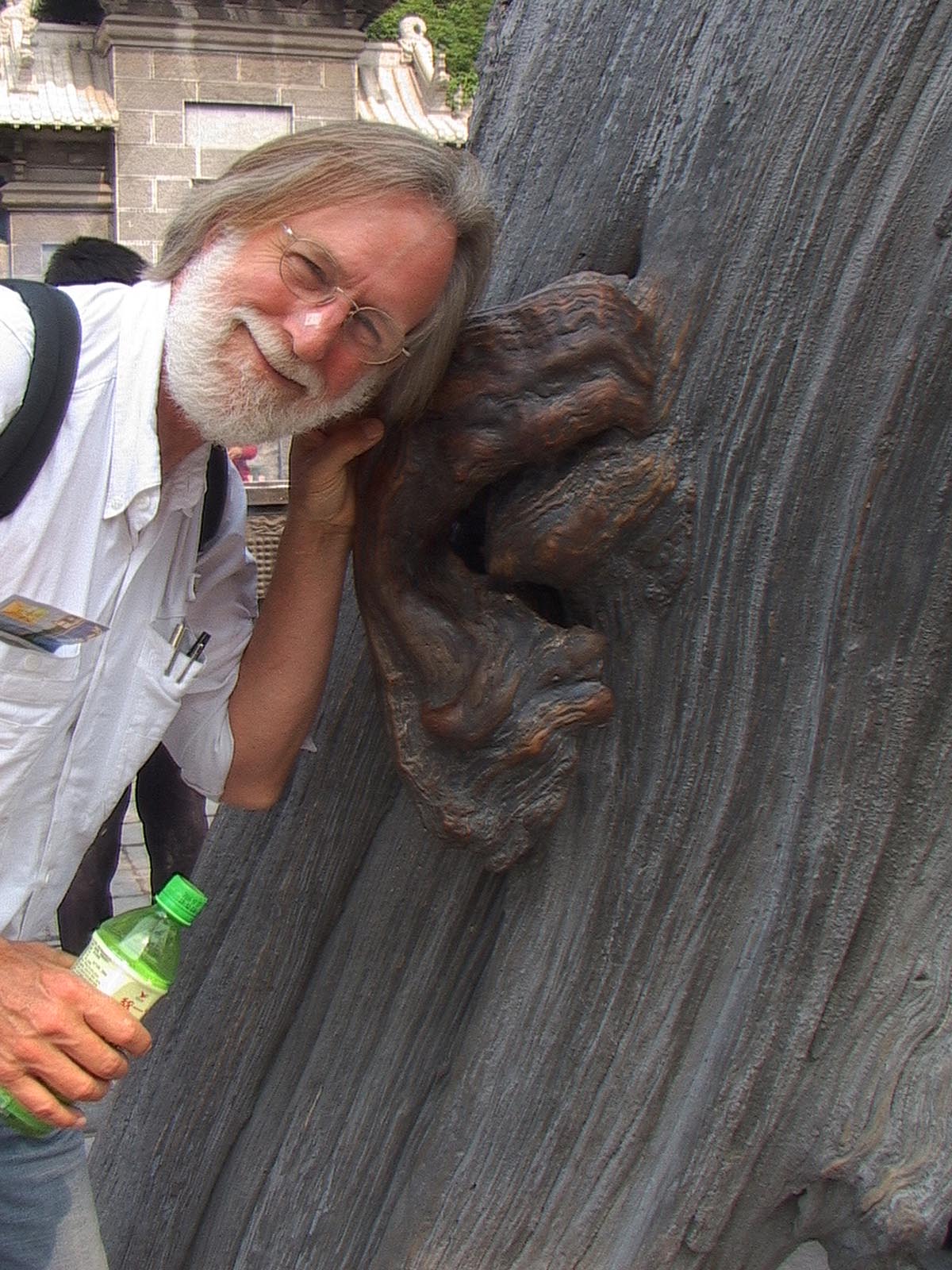

Once upon a time, not so long ago, in 2006, Minnesota poet Jim Lenfestey organized a trip to China to seek the cave where 1,200 years before a Chinese bureaucrat discarded the cares of society to live as hermit poet. St. Paul filmmakers Mike Hazard and Deb Wallwork followed along on Lenfestey’s journey to document his pilgrimage to China as he traveled through the landscape of Han Shan, a poet who’d been a song in his ear, a path under his feet, for more than thirty years.

Cold Mountain: Han Shan (2009), the resulting film, is part bio-pic, part travelogue; it, will premiere Thursday, October 1, at the Central Library in downtown Minneapolis. Before the screening, Jim Lenfestey, a former writer for the Star Tribune, will discuss the trip and read poems from his book A Cartload of Scrolls: 100 Poems in the Manner of T’ang Dynasty Poet Han Shan (Holy Cow! Press, 2006). After the screening, Mike Hazard and Deb Wallwork will discuss making the film and take questions from the audience.

POET BROTHERS

Jim Lenfestey never intended to pick up a book of Han Shan’s poetry. “In the early ’70s my life was falling apart, and a bookstore owner said, ‘Here take these books. They’re small,'” Lenfestey recalls, decades later, from his cottage on Michigan’s Mackinaw Island where he lives and teaches poetry every summer. “The bookseller gave me a copy of Han Shan’s poems as translated by Burton Watson.” In another kind of story, a story about epiphanies, this would be the point at which the character pronounces, “And that book changed my life.” But this is Lenfestey’s story, and the forces that shaped his life are three-dimensional — his wife, his children, his grandchildren.

Lenfestey says, “I’d call Han Shan an older brother. The older brother I never had.” In 1974, when the younger man felt his life coming apart at the seams, what this “older brother” gave him was laughter — maybe the best medicine for difficult times. “I was going on a retreat with the staff members of a school I was running, and I took the poetry books along. We read them aloud as we drove to the retreat site. Han Shan was the first poet who made me laugh; I was amazed.” So how did Lenfestey mark the occasion? “I began to do something I’d never done with any poet,” he says. “I began to write poems back to Han Shan in the margins of the book.”

And then Lenfestey’s life moved on; he took a job at the Star Tribune. Poetry, though still important, was jostled into the background while the young man struggled to get a handle on what Han Shan called the “dusty world” — the world of the city, the world of obligations, responsibilities, red tape, and annual taxes. “I have two friends I’ve known, maybe, thirty years. We meet once a month for breakfast,” says the poet, setting up one of the “moments” in his life. “About 1995, at one of these breakfasts, my friend turned to me and said, ‘Why don’t you take ten of your best poems and make them into a book?’ I’d been talking about and reading my poems to them for years, but I’d never considered publishing any of them.”

Lenfestey did as his friend suggested and, lo and behold, not long after, another friend, a gallery owner, asked him to give a reading. Lenfestey handed out his small chapbooks to the audience members. He says it was an offhand gesture: Here take this. Read it, if you want. Those casually distributed chapbooks “led to some presses hearing about me,” says Lenfestey. He published his first book of poetry.

“There’s this mystical, woo-woo talk about laying out one’s intentions” and those intentions then manifesting in the physical world, the poet jokes. “I don’t believe that for a second.” Even so, he admits, there have been some fine coincidences paving the road to his 2006 trip to China. By that time, Lenfestey had several published collections under his belt and was working as a teacher of poetry. “I developed this mad idea of wandering China, looking for the cave in which Han Shan had lived, to honor him. As far as I could tell, nobody knew exactly where the cave was, or if it really existed.” Then, during a residency to finish A Cartload of Scrolls, Lenfestey’s collection of poems inspired by Han Shan, he opened a translation of Chinese poetry and found a photograph of Han Shan’s cave. He contacted the translator Bill Porter, also known as Red Pine, who, it just so happened, had begun organizing trips to China.

FILMMAKING PARTNERS

Mike Hazard remembers the message clearly: Jim Lenfestey offered to fly him to China. “Jim said, ‘You can make a documentary while you’re there, or not. It’s up to you,'” recalls Hazard, a documentary filmmaker and director of the Center for International Education (CIE) in St. Paul. Hazard has been making documentaries since the 1970s. More particularly, he’s been making documentaries about poets and artists-Robert Bly, Thomas McGrath, Frederick Manfred. In 2006, he collaborated with director Deb Wallwork on a documentary about Minnesota visual artist Charles Beck called C. Beck, a grand prize-winner at the ITVS Short Film Competition.

Hazard says, of course he intended to film the trip to China; and, of course, he intended to frame the story around Lenfestey and his fraternal kinship across centuries with the legendary Tang Dynasty poet. Hazard decided to collaborate with Wallwork on the film, but there was a hitch: there was only one plane ticket. So, Hazard went to China and Wallwork, who had to stay behind in St. Paul, just wished she had. But Wallwork’s part in this journey was no less vital to the project’s successful completion.

Mike returned from the month-long trip with thirty hours of footage and gave Wallwork the footage and his notes, and said, Go for it. “It was overwhelming,” Wallwork says as she remembers the editing process. “I had no idea about the chronology; I had no idea even where they were on the map. But the overall theme of the film was clear to me: it had to be the journey, up the mountain, to the cave, then to the monastery where Han Shan stayed.”

Hazard, on the ground in China, decided what to shoot; to prepare, he’d brushed up on Han Shan’s poetry before leaving. “We walked through a market in China, and there was a bowl of scorpions. I had to shoot that, because Han Shan had this poem about bugs in a bowl,” remembers Hazard, reciting: “Dust, this life is lost in dust/Like bugs in a bowl/We circle, daily, circle/Unable to get out.”

For her part, Wallwork patiently scrolled through the Hazard’s footage, selecting images she could use to tell the story of both the (perhaps) mythical Chinese poet Han Shan (“No one knows if he really lived or if he was a legend,” she says) and of the real-life, poet-pilgrim Jim Lenfestey; she also incorporated a number of related stories, collected from the people Hazard interviewed along the way. Among those Hazard talked to was Burton Watson, the translator responsible for that small edition of Han Shan’s poetry available to Lenfestey in the early ’70s. Hazard also interviewed Beat poet Gary Snyder, another one-time Han Shan translator, and Red Pine, the group’s guide and interpreter in China. Hazard also captured the distinctive sights of what’s become of Han Shan’s native territory: Buddhist monks dusting a temple, incense, traffic, congestion, noise, a busy marketplace, TV commercials, a battery-powered G.I. toy with rifle, and the Butterfly Lady, a laywoman who serves in a monastery kitchen without ever speaking a word.

“It’s a film designed around the people,” explains Wallwork. “Each character has his moment. Each of them fell in love with the poetry and spent years translating it or responding to it. All of them seem to represent different aspects of Han Shan.” Gary Snyder is the rascal who’ll make you laugh. Burton Watson is the scholar. Red Pine is the poet, fully present in the moment. And Jim Lenfestey? He’s the poet as recluse, who leaves the world to seek the refuge of mountain and rock. And I guess that makes Mike Hazard the memory keeper.

“Sometimes this film overwhelms people,” Wallwork says. “So many things are being thrown at them. It’s like a wild road trip though China.” Her co-director, Hazard, describes the film another way. “I went to China and found a fascinating poet and person, Han Shan. You have to keep looking, to ask questions. You have to become a little obsessed. I read everything I could find about Han Shan, and that’s what I hope viewers will do. I hope they’ll walk away from this film and want to learn more about him.”

Not a filmmaker, just a poet with an idea, Lenfestey says the pilgrimage “was never about China. It was always about something inside me. It was an interesting problem, leaving the force field of my regular life to go on that pilgrimage. The trip was every bit what it should have been and much more. The result is the last line of the last poem in my next book: ‘No more dreams.'” Lenfestey is currently putting together another collection of poetry for Holy Cow! Press.

To the “younger brother” poet, who finally got to meet his inspiration — the fellow traveler and muse who whispered in his ear for going-on forty years — “no more dreams” does not mean the end of the relationship, but rather a “softening of the edges. Lenfestey describes this fresh understanding as a new sort of kinship, horizontal and green, rather than vertical and mysterious. He says, “It’s become an everyday relationship, a now relationship.” Lenfestey goes on, “I have a theory: I think we all find that artist whose work speaks to us. For me, it’s Han Shan. And what’s funny is that he’s a character who lived 1,200 years ago, if at all.”

Related events: Get details about the Thursday, October 1 screening of Cold Mountain: Han Shan at the Hennepin County Central Library, which will be accompanied by a poetry reading and Q & A with the filmmakers and poet Jim Lenfestey, on the Hennepin County Library website.

About the author: Britt Aamodt‘s book on Minnesota’s contemporary cartoonists (Off Color) is coming out fall 2010 from the Minnesota Historical Society Press. Aamodt reports on the arts for KFAI radio in Minneapolis, and is the founder of the radio play group Deadbeats On The Air.