A Phoenix Rising: Elayna Waxse

Lightsey Darst profiles dancer Elayna Waxse: what happened when she lost her passion for ballet, found a new fire, and came back to dance in a way neither she nor anyone else ever expected.

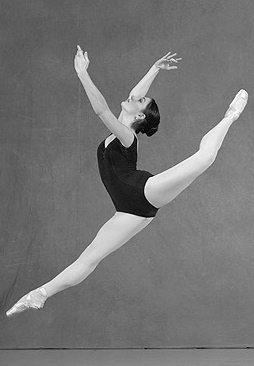

ELAYNA WAXSE’S STATUS UPDATE for February 1st, 2013: “The day I finally throw out my pink tights.” In 2007 Waxse spun like a jewel at the heart of Minnesota Dance Theatre’s sumptuous Nutcracker Fantasy, in the featured role of the Queen of the Flowers. What happened?

What happened is that she lost her passion, found a new fire, and came back to dance in a way neither she nor anyone else ever expected. “I kept sticking my leg up on the wall. I decided I was flexible”—so Waxse, as a child, decided to try ballet. Her mother warned her she wouldn’t like it; she was a tomboy, into soccer and swimming. But “the very first class I took,” she felt lightning: “This is what I want to do.” Six months in, she told her parents she needed to quit the rest of her activities because she was going to be a dancer. Her parents laughed, but they let her, and she excelled, leaving for the Pacific Northwest Ballet school at sixteen. This resulted in her not finishing high school; she meant to, but the correspondence courses were too much of a bother, and anyway she was becoming a ballet dancer.

Not that it was an entirely smooth path. Waxse “always had issues with the body type,” and, for a born rebel, the authoritarian ballet culture “was always something I struggled with.” But her enthusiasm for movement and her sheer ignorance—“I didn’t have a lot of knowledge of dance outside the ballet world”—carried her through. She loved to dance, and this was dance.

After a few years at MDT, Waxse went on to a bigger company, Denver’s Colorado Ballet, for a year, but the work was too classical, so she quit and came back to guest with MDT. By then her heart wasn’t in it. As she puts it, “I was good at being told what to do, and then eventually I got sick of being told what to do.” In the meantime she was looking for another ballet job, but it was 2008, year of the financial collapse. She went to Washington Ballet and saw “the Fanny Mae Rehearsal Studio,” Fanny Mae this, Fanny Mae that. They weren’t hiring; no one was. In fact, New York City Ballet laid off an unprecedented eleven dancers that season. The quick ripple from the financial sector into big ballet became another reason Waxse “got over” the whole ballet thing: how could she go on pouring passion into an artform debased into the harmless pet charity of the banker’s wife?

Another reason was a serious and mysterious ankle injury. Waxse danced MDT’s Nutcracker in 2009 with a fake arch masking her failing foot, then took a little time off. A little time turned in four months, and then she had to admit it to herself: she was done.

It was the beginning of 2010. Waxse was twenty-three. She had no high school diploma, no idea what would become of her life, and she’d just given up on her first love, the desire that had ruled her for years. “I could not comprehend being as passionate about anything as I was about dance.”

I used to see Waxse around this time at her bartending job. She didn’t look happy; she worked down the street from a dance theater, and she must have seen reminders of her old life every weekend. I was sorry she wasn’t dancing—I missed how her adult attack and dramatic presence complemented her friend and MDT compatriot Melanie Verna’s creaturely explorations—and yet I wasn’t altogether surprised. Waxse hadn’t looked fully absorbed on stage in the past few years; she performed rather than transformed. Besides, her dark energy was the kind that can burn itself out or spill into the usual distractions—boyfriends, parties. I’d seen it before. Or I thought I had.

That time “was really scary,” Waxse says. Still, “I’ve always been very stubborn, so I never allowed myself to go into full identity crisis.” Instead she got her GED and went back to school, first to MCTC, then to the U of M. Looking for a field that could compel her, she started a degree in social justice. What she learned there steeled her resolve not to go back to dance. In ballet, “night after night, you’re essentially performing for rich white people.” And since ballet was dance, was art, she reasoned that art didn’t serve social justice. (She knows better now.)

Waxse also followed up a desire that had haunted her for a long time: she got a phoenix tattoo. “I first wanted it when I was seventeen,” she says—before she had a need for the phoenix’s redemptive myth, and before it seemed possible to follow her desire. Classical dancers must be unmarked; for a female dancer just starting out, a tattoo would have been professional suicide. From seventeen to twenty-two, Waxse wondered where she could tuck her phoenix so it wouldn’t be seen. But now it no longer mattered, so Waxse got it big: the phoenix starts under her shoulder blades and covers her back well past her hip. Getting it was “my assertion of ‘I’m done with this,’ ” she says—though the other half of the phoenix’s story, the rebirth, wasn’t clear: “Now I’m reborn as a bartender,” she jokes.

(Waxse is not the only tattooed ballet dancer in town. Nic Lincoln has some, and Nicky Coehlo has a line of beautiful script down her lower leg—both stories I’d like to hear sometime. But Lincoln and Coehlo both dance for James Sewell; they don’t do traditional ballet.)

______________________________________________________

“Ballet isn’t allowing itself to evolve at the same rate as other forms.” Defenders of the faith keep the name narrow, so that the artists who might do the most to bring new life to ballet keep finding themselves outside the gates.

______________________________________________________

Waxse also went on an adventure: she flew to Asia, climbed the ancient temples of Angkor Wat, took a rickety ferry to a paradisiacal Thai island, and in Vietnam she went to a shooting range where she fired a Viet Cong AK-47. When she came back she posted a photo of herself aiming the gun as her Facebook profile image.

She’d come a long way. But she hadn’t come back.

For a while, “I never considered going back to dance. I wouldn’t even allow myself to watch dance videos on YouTube.” But the aversion ebbed with time. When she realized that, as a full-time student at the U, she could take extra classes for free, she thought why not? and signed up for a class in modern dance.

I asked her whether she was nervous, or worried she wouldn’t excel. Contrary to what people often think, dancers do not always find it easy to change forms. Being good at ballet does not mean one will be good at modern dance, which requires a looser body, more attention to breath, and a curving sense of motion. But Waxse didn’t go to class thinking she would excel. “I don’t dance anymore, I have nothing at stake,” she told herself. She was only there because “I want to explore different ways of moving.”

That exploratory attitude caught the eye of Carl Flink, who suggested she audition for his company, Black Label Movement. She did, and wound up dancing for him last summer and fall. She also started taking class at the TU Dance studio, which led to Toni Pierce-Sands asking Waxse to join TU Dance. In six weeks she went from a bartender and student to a professional modern dancer.

Now Waxse is exploring in all directions. She’s taking different classes—a Gaga intensive was her latest exploit—and going out to see dance (she enjoyed Chris Schlichting’s Matching Drapes last weekend). She makes fun of her own prior ignorance: “Who’s Pina Bausch?” These days, she’s “almost obsessively fascinated” as she discovers a wider dance world, in which she’s finding “all these incredible artists.” TU Dance provides a happy home base: “I love working for Toni and Uri.” Recently, her experience with the AK-47 came in handy when TU worked on a military-inspired piece, and Waxse was able to explain the feeling of recoil to her fellow dancers, none of whom had ever fired a weapon.

And her phoenix tattoo? She worried when she first had to tell Uri Sands about it, but he was quick to reassure her, “No, don’t cover that up at all.” It’s part of her body, part of her life in a way she didn’t foresee when she got it. “Now it has a totally different meaning,” she says.

What’s next for Waxse? One big discovery is her own work, recently featured in a showing in Detroit. She felt some desire to choreograph before, but no interest in the dance vocabulary she knew—it was “one of the first signs that I wasn’t right for the ballet world.”

I have an indelible memory of Waxse in ballet class, around 2009, rolling into a little Balanchine hip-flip, a flirty step out of Duo Concertante, not traditional, and unusual for class. Waxse had it down, but you could see that the moment after she did it, she didn’t care: one more tiny twist on the classical vocabulary could hold her attention only so long.

What does she think of ballet now? “It’s definitely not allowing itself to evolve at the same rate as other forms,” she says. It’s not that ballet’s legacy isn’t fruitful, but the defenders of the faith keep the name narrow, so that the artists who might do the most to bring new life to ballet keep finding themselves outside the gates. As Waxse remarks, for many in the ballet audience, deviance is turning your leg in instead of out. She tells a story to underline the point: when she had her ballet students do Horton technique (modern) instead of ballet one day, barefoot, to drum music, they called it “African dance”. Anything even slightly different, to them, was so strange as to be “ethnic”.

Which brings us back to the pink tights. “I have no need for them anymore,” she says: she’s done with that kind of dance. “I kept the pointe shoes,” she adds. “I would consider putting those back on—but not with the pink tights.”

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl was recently published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She writes a weekly column on dance for mnartists.org.