A Leveling and an Evening

Writer Alexis Zanghi responds to works by Candice Davis, Nancy Julia Hicks, and Judith Holo Shuǐ Xiān with Dua Saleh at the recent Mn Artists Presents event, proposing how the museum might proceed through a politics of harm reduction, towards an ethics of care.

“We heard a huge noise,” a worker told the Evening Standard, “and the building collapsed within a few minutes.”1 The collapse of textile factories at Rana Plaza in Dhaka, Bangladesh, is considered among the most destructive structural failures in recent human history. A structural failure occurs when a building fails to bear its own weight; it is a failure of engineering and design, of structural integrity. More than 1100 workers died at Rana Plaza, and another 2500 survived with injuries. As bodies were pulled from the rubble, another worker told the Standard: “I was at work on the third floor, and then suddenly I heard a deafening sound, but couldn’t understand what was happening.”

During the moment of trauma comprehension becomes overwhelmed by sensory input and the body muscles an arsenal to response: temperatures rise and fall; lungs seize for air; eyes process light and darkness in new and different ways; white blood cells reorganize themselves; genes fragment and then rewrite themselves in new sequences and are transmitted to another generation, the social production of trauma is reproduced. Hearing becomes distorted as part of an exaggerated acoustic startle response: a survivor may experience auditory hallucinations such as paracusia, the term for hearing voices, or ringing in the ears, called tinnitus; they may experience a fear of some sounds (misophonia) or all sounds (phonophonia).

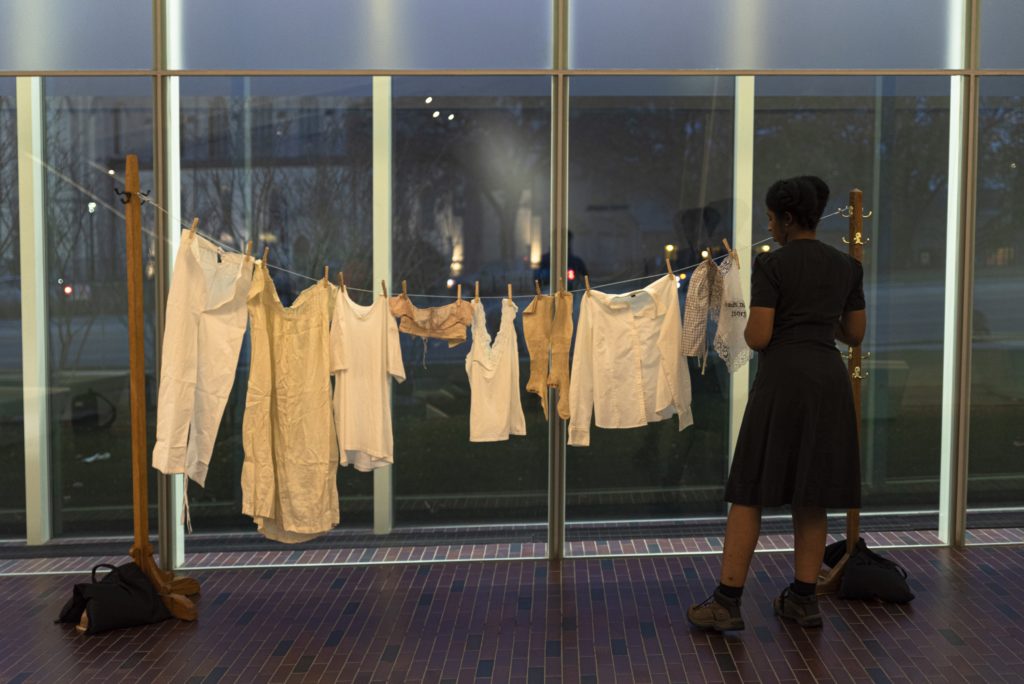

The work of survival becomes its own labor. In My Ancestors’ Tears At Dhaka, Candice Davis uses an antique hand-operated laundry press to press stenciled texts onto white fabrics: a laundry press turned letter press. Davis has braided her hair in a crown along the back of her head and she wears a black dress evoking uniforms historically associated with domestic labor. Laundry work can be paid by the piece or by the hour or—for enslaved people—not at all. Davis works quickly and quietly, stenciling, wringing, and hanging the stenciled fabrics along a clothesline. When the works are done, they read: “Man is not a machine/Land is not a factory.” The exertion of structures of violence upon man and land results in the violation thereof, a structural fulfillment and failure at once. Through the performance of labor—which is also itself labor—Davis restores man and land from production. Her declaration reproduces itself in the wide glass walls of Hennepin hallway, transposed against the walls of St. Mark’s Cathedral, refracting over headlights into night.

The act of surviving reorders the survivor’s world and the ways in which they perceive it. Many do not experience trauma as a singular event with a clearly demarcated before and after; rather it is something tidal, with its own timing—trauma can recur, is transmitted from one generation to the next; what happens in one night can feel as though it lasts for years, an instance of trauma can be forgotten and then sweep inward, in a single motion; it becomes difficult to contain trauma to the event: an evening transcends its own duration, leveling into experience.

The walls inside the cinema are soft and insulated; sounds from the films land gently around the audience. Paul Chan’s Baghdad In No Particular Order (2013) plays between short videos by Davis and Nancy Julia Hicks. Hicks’ two-part video, Body as Rig, positions their naked body on all fours, at first on land and in the mud, in areas that have been marked as “productive areas” and “productive wells” in overlaid transparencies of land surveys. Trauma is marked out at the site of extraction, levels into its own topography. The following video moves Hicks into a white gallery space, where they (now clothed) return to all fours, with a white tablecloth set on their back. The body is not a commodity, nor is it a site for extracting raw materials—instead, it becomes quietly subsumed into a service economy. The image of the tableclothed Hicks gives way to a transparency of an oil rig. The site of production is no longer outdoors, and production does not involve the extraction of a commodity from the ground; in the anodyne service economy that Hicks presents, their body is both “emissions and product”—a by-product of extraction, freed from commercial exchange. This declaration of what one’s body is against, what is transposed over and imposed upon the body, gestures towards the healing that is possible within the current mode of production, and necessarily to its dismantling.

In Chan’s film, a Baghdad bookseller recites poetry from memory for Chan’s camera, declaring that he has “tears in my ribs,” and “Lorca, Lorca, Lorca.” The camera cuts to the bookseller seated in a folding chair, his books arranged for sale on the side of the road. What follows is a girl smiling and dancing in her school clothes and a sweatshirt, and then a monkey sleeping in a too-small cage. I have to leave.

From inside the Walker’s lobby, Hicks leads the group from the building to the Walker’s grounds, reciting poetry that I can’t hear while wearing a felt vest covered in 92 cement bricks. As they circumnavigate the museum three times, their feet and those of the audience crunch leaves and grass. I can hardly hear Hicks’ voice over their footfalls. I remember a line from Hicks’ video: “What will you do when the floodwaters come?”

Candice Davis, My Ancestors’ Tears at Dhaka. Photo by Pierre Ware for Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Candice Davis, My Ancestors’ Tears at Dhaka. Photo by Pierre Ware for Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Nancy Julia Hicks, You don’t see it, do you? / The hand and the body. Photo by Pierre Ware for Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Nancy Julia Hicks, You don’t see it, do you? / The hand and the body. Photo by Pierre Ware for Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

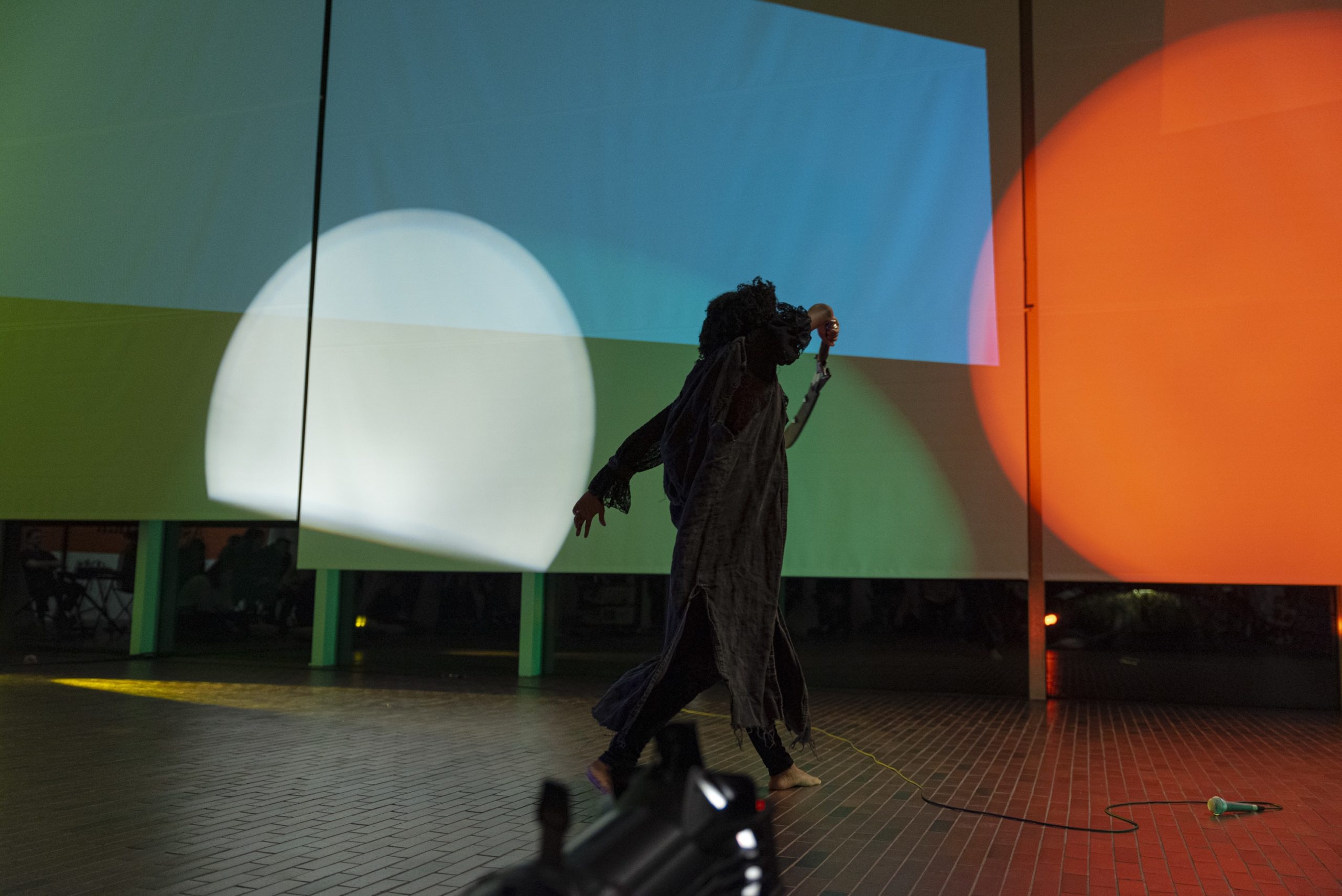

Judith Holo Shuǐ Xiān begins their performance with Dua Saleh with both artists clutching themselves into a corner of the Cargill Lounge. As each performer murmurs and gurgles against their microphones, they begin to pull away from one another. Wearing a pair of white denim overalls, Dua Saleh peels across the glass and into the middle of the lounge slowly; Shuǐ Xiān circles outwards, unfurling themself towards Hennepin Hallway. When the pair meet, they clutch against and towards one another, rolling over each other until they reach the soft sheen on the bricks. Saleh rises, a black cloak covering their overalls, and there is the sound of a sword dragged along baked bricks, loud as mouths on microphones and bare feet on the windows and floor. Then Saleh begins to shout, furious and fearful at once, and paces against the edges of the audience until Shuǐ Xiān returns. They fall to the ground together, then return to each other, reaching, safe and still. I feel cold on the floor and I pull my hat over my ears; the sword rattling against brick is loud as though something has broken, is breaking.

If we understand the museum as a site of trauma—as a site of material and social production, as an institution that produces and reproduces hierarchical forms of power—then what would a politics of harm reduction look like in the museum? The museum exhibits representations of trauma; it also represents the trauma of oppressed and colonized peoples. It reproduces that trauma in a material way: through exploitative hiring practices, solipsistic exhibitions and exclusionary collections, and its essential and complicit role in the continued extraction, accumulation, and hoarding of wealth by elites and corporations. A politics of harm reduction can be understood as a set of practices through which artists, audiences, and workers might create an institution that does not produce but generates, and that does not preserve but tends—practices that are simultaneously an end in themselves and through which the museum might become a site of care. (A politics of harm reduction within the museum can look like recent protests against the Sackler and Zabludowicz foundations and increased scrutiny of museum board members, as well as union drives by museum workers and art handlers; it necessarily includes the active decolonization of museum exhibitions and collections as well as institutional memory and resources.) It entails the recognition that as a structure the museum is one of violence by design, that it is not isolated from but integral to oppressive apparatuses, that its fulfillment is also its failure.

Like structure and practice, politics is both a transitive verb and a noun: it is something one does and something an institution can do and something individuals can do collectively, together. Interpreting these performances as discursive endeavors risks reinforcing the museum’s positioning as dominant structure while withholding autonomy from the performances themselves. If the performances draw from the museum as site and form, it might imply that the performances are somehow contingent upon the museum. If the performances by Davis, Hicks, and Saleh and Shuǐ Xiān are interpreted as autonomous endeavors and ends in themselves, then that interpretation risks eliding the violence inherent to the museum but offers the promise of undoing that same violence.

Privilege is frequently described as something that one has, which makes it seem inert and ossified—white like a bone—rather than a metabolic function of extractive and actively exploitative processes. Privilege, like politics, is also a verb and a noun: one can have privilege, but one can also privilege a person or thing or view over another; privilege is a verb that exerts itself through exploitation. The museum is a place that reaffirms and reproduces privilege, and the inherently transient nature of the evening’s performance prompted the moderator, Esther Callahan, to ask of the artists, “Does it honor or other you?”

Both are transitive verbs and nouns: one can honor another or hold honors; one can be othered, be the other, or other. The artists responded to Callahan’s question with a both/and. The aim of the evening had been in part to rupture the space of the museum with sound, to intervene upon the structural through the temporal. Chicasaw scholar Jodi Byrd begins The Transit of Empire2 with a critical indigenous reading of the colonialist discursive structure of the parallax, “a shift in an observer’s standpoint of a distant object based on a change in vantage point.” This shifting allows the observer to triangulate the distance to the object, which became a measure through which colonialism came “to map, own, and know the earth.”3 What is needed are new structures, new measurements and practices which are incommensurable with and unknowable to the nation-state’s ways of apprehending—a reclaiming of the parallax and a triangulation that begins with indigeneity “as an ontological prior”, that ruptures the normative spaces and structures of the settler nation-state. Through such a shift, the museum as a structural formation would no longer be the source of recognition and regard, of othering and honoring. The museum4 would shelter and build through a politics of harm reduction towards an ethics of care.

Near the building exit, Hicks set their vest on a small hanger: a skeletal outline of itself against the glass in the early evening dark.

This writing was commissioned as part of Mn Artists Presents: Jonathan Herrera Soto.