Eating earth, cleansing bones: Notes on a family exhumed

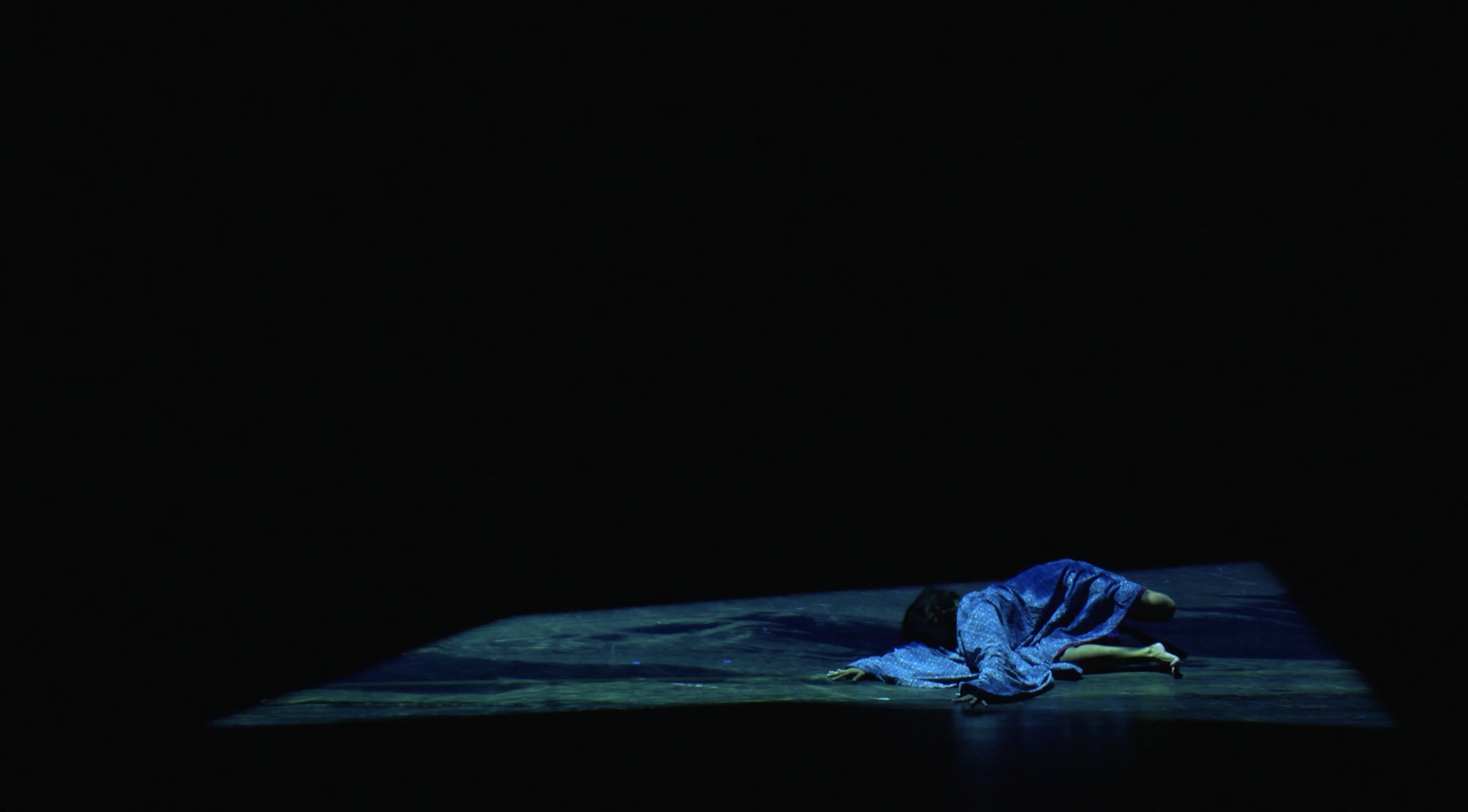

Moving image artist R. Yun contemplates the violence buried in multiracial family lineages, intimate misrecognition and the anthropological gaze, internalized racism and the politics of renaming oneself.

I see my face and I see you. Dark eyes, furrows around nostrils like parentheses. Woman, immigrant, other1… a languishing mouth that turns downward at its corners, this face yields something cavernous and secret, often mistaken for antagonism (in your case, this is no mistake). You taught me to hate the part of me that is you, because it is what you hate in yourself. You thought that by marrying an American (who you didn’t know was only half American—you barely spoke the same language), I would be spared from the same curse that you’ve carried and tried to transcend. The one that you believed because they told you it was true. That because of your straight black hair and your angled eyes, you were less than them. You swallowed it whole, changing every part of your name and never turning back. You wish you were white. You wanted your children to be white, and their children to be whiter still. But when you look at us, what you see is not the whiteness that you so desire. Instead, you see the part of my father that you hate and you see yourself, and you can’t bear it. And that is why you left.

***

Often I think of Amiri Baraka. Not solely for the radical literary work I came across as a young student—Dutchman, Blues People, The Slave—but because of an experience that shook me when, still young and naïve, I saw him speak. The event began with reverence and it ended with mutiny. A woman in a headscarf spoke ardently about the imperative of returning to the “Motherland”—a concept that Baraka swiftly and vehemently denounced with a diatribe on the ignorance of young black folk (the majority of his audience). His words cut far too deep. People yelled and jeered, exiting in pandemonium. I watched, remembering how Baraka, 30 years earlier and still LeRoi Jones then, had also sought a Motherland. He divorced his first wife, Hettie, a white Jewish writer, married black author and activist Sylvia Robinson, and moved to Harlem. Jones became Baraka. I think of his bi-racial daughters. If loving Hettie had become impossible, how did his young daughters fare in the spectrum of love and political sanctity? The internalized racial oppression that my mother embraced is what Baraka spent a lifetime elucidating and resisting through his poems, plays, and essays. But we, the children of duality, are in constant and innate flux, and we take our cues from our kin. From our skin.

***

***

Miscegenation. A clinical word to explain how I came to be. Latin root, English suffix, like so much empirical vernacular devised to define what I am (a product of an historically defiled and illegal act). When I was young, people around me used far less scientific terms. They told me what I was, and they took pleasure in doing so. The appellation that aroused the most glee was repeated often: the small, blunt word “mutt”. Today I type “miscegenation” into Google. Its listed dictionary definition, “the interbreeding of people considered to be of different racial types,” appears above a series of photos of dogs, without explanation. Is this an internet coding error? A glitch? A calculated hint? People as animals…

***

“Mejorar la raza” is a common expression among Latin Americans.

***

Nostalgic and emphatic, my father would compulsively recount to my brothers and me the ruptures he had experienced in his childhood and adolescence. His mestizo mother had died so very young, causing a deep chasm forward into the descendent line: two dichotomous families, one white, one darker. Thus as a child, I knew that he had been called “half-breed” and “Indian” by his white Hispanic stepmother and his white half-siblings. Later you would call him names even more vile. Like the legacies of families that flow through blood, I began to understand that his persecutions had become my own. Because he married you, I was marked in an analogous way. My angled eyes elicited injurious commentary, but they made sense next to you. After you left, what people saw was a “dirty Mexican” with three “Chinese” children. We weren’t Chinese, and he wasn’t Mexican. But he was your half-breed ex-husband, a.k.a. my father, and we were drowning in our illegitimate identities. Our proximity to each other, normally reserved for care and endearment, became heavy with indignity.

***

A common nickname in Latin America for those perceived to have indigenous, even Asiatic, features is “chino”. A neurotic code to repress the centuries of ethnic and racial admixture, amalgamation. Once I was walking in El Vedado, a neighborhood of Havana. A crowded pink camello bus passed by me with one hundred people inside. The bus driver pointed and yelled, “!Miran a la china!” and one hundred people looked at me and laughed.

***

***

You run when you must move through the sun without something shading your face.

You tell me that the sun is the devil, that I should stay away.

You hate the color black.

I worship the sun, can’t live without that which you tell me to disdain.

Just as it is impossible to wipe the image of your face from mine.

***

She is 46 years old. She is the same age that George Floyd was on the day her white husband murdered him with the full weight of his blue-uniformed body upon his black neck. “Irretrievable breakdown” is the reason cited in her divorce filing days later, only after our city burned and thousands marched while breathing smoke, tear gas and the COVID air to demand his arrest. His name is Chauvin, the very eponym of “chauvinism”. She declares that she wants to rid herself of his name, this word, and I wonder if the contamination (its meaning), this embodied substance with which she lived for ten years in marriage, can be cleansed from the body, from the mind. When our intimacy is colonized by racism, can we ever return to our former selves?

May Thao: Born in Laos, brought to America as a refugee with her family at age 3. Urged by her parents to marry Kujay Xiong at age 17.

Kellie May Xiong: Divorces Xiong, stating “abuse” as the reason. He dies shortly after. Supporting two sons, she earns an associate degree in radiology and a position at the emergency room of Hennepin County Medical Center. Officer Chauvin escorts a suspect into the hospital. He sees his “future wife”. He takes the suspect for arrest and returns for her. They marry.

Kellie Chauvin: Becomes the first Hmong Mrs. Minnesota, a beauty pageant winner with a wide smile in an emerald green dress and a tall, jeweled crown. She tells the press of her police officer husband: “He’s such a gentleman.”

Kellie _____ :2

***

***

One reviewer of Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds observes his poetry as “a conduit for a life in which violence and delicacy collide.”3 Indeed Vuong alludes to the violence of war and the delicacy of love as marking his very existence. His grandmother, a “Vietnamese farm girl,” and his grandfather, an American soldier from Michigan, had his mother, who had him. In “Notebook Fragments”, Vuong plainly writes, “no bombs = no family = no me.”

My own story is marked by the same war, the same bombs. If it weren’t for that war (the “American War” from the Vietnamese perspective), I too would not exist. In Vuong’s life story, his grandparents were unintentionally separated because of the fall of Saigon, not for lack of the delicacy of love. In my story, the original violence of my existence lies within my family itself. It is the site of the racism that swelled between its players. And like Rebeca eating earth and dragging a canvas sack with her parents’ bones in Gabriel García Márquez’ 100 Years of Solitude, I have carried it with me. My mother bargained through marriage to come to America, to leave that “third world” country to become civilized, whitened (she changed and westernized every part of her name.) My father, though he fought for America with his life, had more allegiance to the family who didn’t treat him as half of a person, and who taught him who he was. He had another culture, another family, another home where he’d been born and where he had been sent back as an adolescent. It was there where he wanted to return after the war. My father took her to this place, and it was another “third world”, even more impoverished than hers. Dirty and smelly, just like him…like her children. She could never forgive him for his deception. And she left.

***

Irretrievable breakdown: Permanent, beyond repair.

***

I remember watching you watch the television screen. A young girl studying her mother, perplexed by what she could not yet comprehend. It was your favorite of the Olympic games, the ice skating competitions. “They are so graceful.” Your eyes, so full of desire. A Russian skater with her hair tightened back in a sequined bun. Blue eyes sparkling and beaming. Without looking away from the screen, you said, “Caucasians are the most beautiful people on earth.” My heart was like an ocean pumped suddenly, violently dry. I wanted to disagree, for your sake, for mine.

This article is part of the series by guest editor Christina Schmid