A Citizen Artist in a Country at War

Camille Gage on "choosing the street rather than the studio" and making an artistic life built around "working in support of the common joy and public good." Her new project, "No Glory: 10 Years and Counting," opens today at Form + Content in Minneapolis.

“It is something to be able to paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look…To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts.”

Henry David Thoreau

IN OCTOBER, 2011 I WILL COMPLETE AN 18-MONTH COLLABORATIVE public art project — an ambitious, some might say crazy, nation-wide public work to which I will end up giving over 1,000 hours and for which I and my artist partners will receive no compensation. I will work on this project long into the night, on weekends, and on sunny, summer evenings when I’d rather be out playing. To paraphrase the Talking Heads, “How did I get here?”

“Public artists”, “new genre public artists”, “cultural workers” — in the 20+ years I’ve been at this, none of these labels ever really sticks. Why would I, and others like me, choose to devote a good portion of my creative output to such work? It’s a genre that falls in and out of favor with the academy, with funders and critics, and which almost always requires collaboration, cajoling, and lots of time spent on projects whose outcome are often largely outside our control. It’s an artistic path that, while getting occasional critical props, often defies even post-Greenbergian notions of what art is or should be — one that, despite major strides towards recognition, still too often requires that its practitioners answer the familiar question, “But is this art?”

Like Duchamp’s R Mutt in its day, what we do is indeed art: a contemporary practice pushing the boundaries of form and content. I and a growing number of artists find the line between art-making, community involvement, and personal activism to be non-existent, or at least blurred beyond recognition, and our work reflects this reality. Our creative output is a seamless amalgam of topical art-making, community organizing, and the unwavering belief that art has a role to play in shaping both civic consciousness and the health and happiness of our communities.

We are citizen artists working in support of the common joy and public good.

I’m not sure why some artists choose the studio while others choose the street. I can only tell my story, and it begins with war.

I came to the age of cultural awareness, of life outside my family, during the nightmare of the Vietnam War, the sobering debacle of Watergate, and subsequent impeachment of the President. Like so many others my age, I developed a strong aversion to war and its black hole of violence, witnessed by news photographs of innocent children burned by napalm and critically wounded soldiers being air-lifted out of fetid fields. I distrusted what seemed to me a feckless and deceitful administration that could neither articulate a meaningful, rational reason for continuing the war and its entanglements nor a way out.

To me, art, theatre and music offered universal truths, powerfully articulated, that provided an antidote to the lies and half-truths underpinning the violence of war. I was hooked on the idea that art could articulate a new vision and make a difference in the world.

I listened to the radio and read Rolling Stone cover to cover. Alone in my room, in a Rust Belt town I devoured journalistic accounts of creative rebellion and listened to music night and day. I watched the emergence of a significant community of artists, whose music, theatre, and art met the intensity of the cultural moment head on; alt-radio and press brought their work into the heartland. John and Yoko’s Bed-In, Melanie singing “Lay Down“; the Jefferson Airplane’s brash “Volunteers of America“; the play HAIR, Neil Young’s searing “Ohio“, and Marvin Gaye’s visionary and musically spectacular What’s Going On are just a few of the works that had a huge impact on me.

To me, art, theatre and music offered universal truths, powerfully articulated, that provided an antidote to the lies and half-truths underpinning the violence of war.

I was hooked on the idea that art could articulate a new vision and make a difference in the world. I’d found my path.

In the years since the 1960s and ’70s, the role of activist artists and creatives engaged in public or community-based work has grown, morphed, and evolved in myriad ways. In my formative years, politically-oriented public artists were, for the most part, firmly planted on the fringe. Things have changed. Contemporary public artists often work in subtler ways now, sometimes in their own neighborhoods; they are, as eco-artist Christine Baeumler puts it, firmly “embedded in their communities.”

Artists now have the opportunity to work not only as makers but as facilitator/catalysts of change, or some hybrid of the two. The artists who choose public work continue to push those genre boundaries and explore new ways of working in community. Many such explorations involve knocking down the long-standing hierarchy of artist as creative expert and public as consumer. Many public practices require the participation of all involved, whether they self-identify as artists or not. Indeed, central to my public practice is the encouragement and recognition of the innate creativity in all people — and further, my work acknowledges that this powerful force needs and deserves an outlet, and that the provision of such can and will change communities and our world for the better.

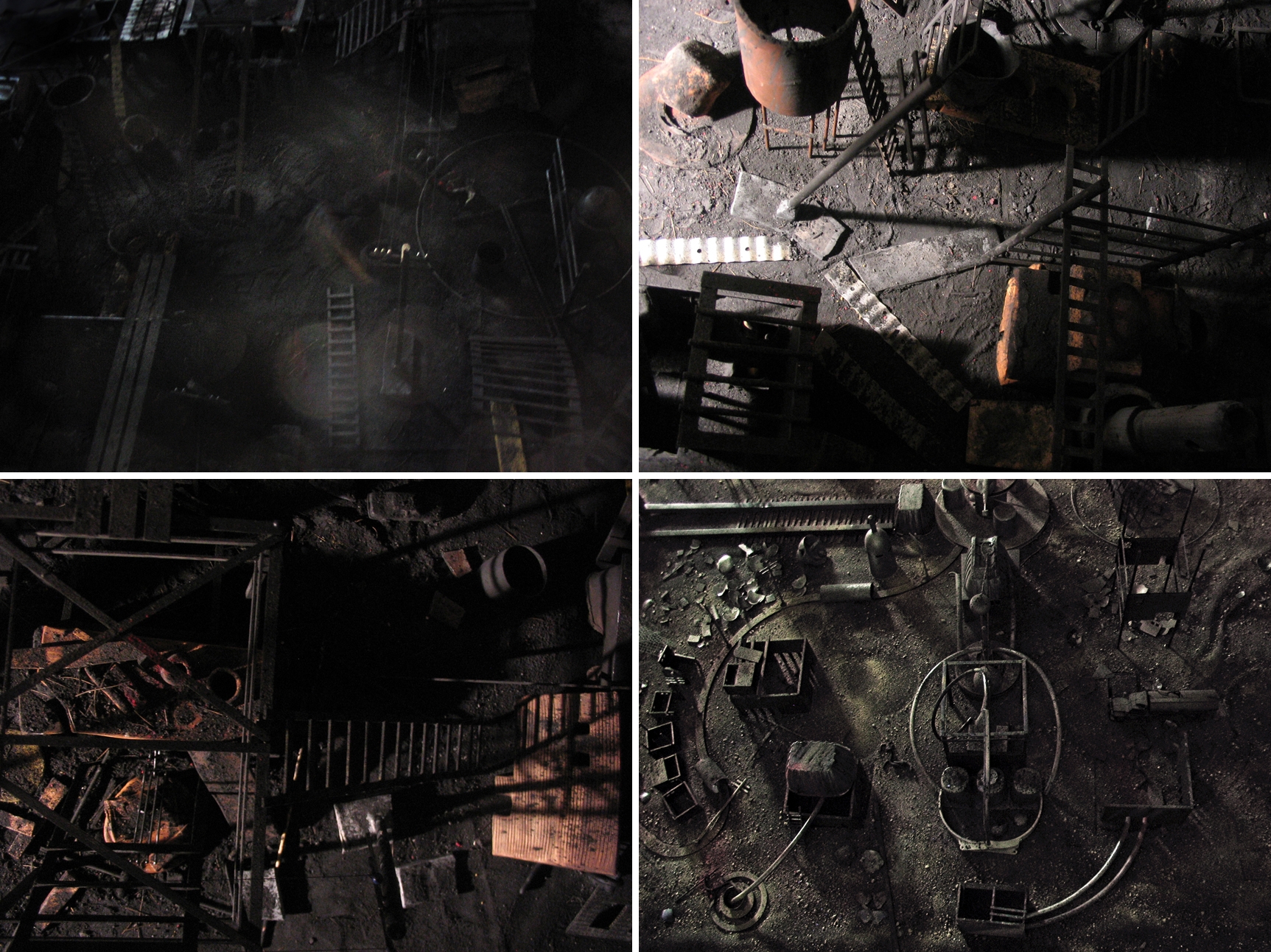

When the war in Iraq began, the first thing I noticed was the absence of images of the war dead. No images of civilian casualties or fallen U.S. troops. No images of the somber honor guard ceremonies that await each flag-draped transfer case.

As an artist I fully understand the reason for this absence. I understand the power of these images and why they were missing for so long from the coverage of the wars and our cultural dialogue about it. But war is not the antiseptic event we’ve been sold in the last decade, with its “surgical strikes” and “collateral damage”. War is brutal and people die. Our young enlisted men and women, innocent bystanders, and thousands upon thousands of children die horrible, often excruciatingly painful deaths. Seeing gruesome evidence of the war we’ve engaged in pierces the heart. Seeing these grave images might soften the forces of anger and righteous patriotism that fuel it. As a nation, we did not want to look. And so, we have not looked. And 10 years have passed.

To me, art, theatre and music offered universal truths, powerfully articulated, that provided an antidote to the lies and half-truths underpinning the violence of war. I was hooked on the idea that art could articulate a new vision and make a difference in the world.

In an essay titled “Where Are We?,” written for Harper’s shortly after the start of the wars, John Berger writes of the cost of willful ignorance:

“I write in the night, although it is daytime…I write in a night of shame.

By shame I do not mean individual guilt. Shame as I’m coming to understand it, is a species feeling which, in the long run, corrodes the capacity for hope and prevents us looking far ahead. We look down at our feet, thinking only of the next small step.”

My current project, the aforementioned 1,000 hour project, is an attempt to raise our collective gaze, to shed the shame and guilt that surround our nation’s ongoing military engagements and use the power of creative energy to spark a fresh dialogue about becoming purveyors of peace, not war.

10 Years + Counting grew out of a focused residency at Blue Mountain Center in New York. Twenty-four artists, writers, filmmakers, academics, and activists convened to discuss one thing: the cost of war. It was a sobering week, and a handful of us left the residency determined to stay in touch and figure out a way to do something. We knew that the ten-year anniversary of the war would provide an unusual opportunity to re-capture the dialogue.

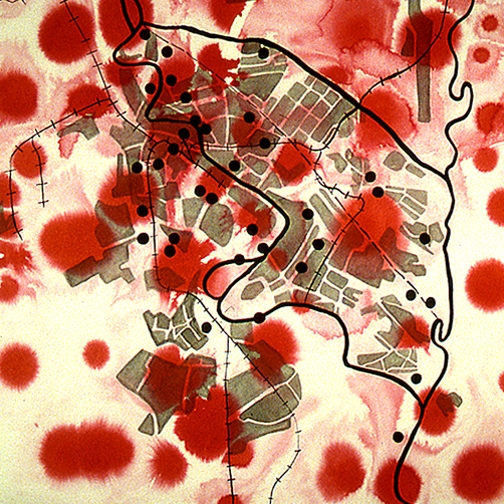

Collaborators on the project are scattered across the country. Through email and conference calls we hammered out the details: What is the appropriate medium given that we are few but want to create something with national impact? We decided to exploit the internet as a public space, to create a cultural commons that would encourage creative responses to the ten-year anniversary of war. Ours would be a project that would not prescribe action, but rather challenge individuals to work within their own homes and communities and bring their own interests and passions to bear. As it says on the 10YAC site, we aim to turn the “anniversary of devastation into an unstoppable, irrepressible explosion of imagining the possible: a new beginning.”

It’s a lofty goal, but the multi-disciplinary team that is directing 10YAC believes that creativity is necessary for change. There is no way to devise a better future, or an end to the war, if we cannot first imagine it. Socially engaged public artists are well-equipped to lead the way, to tap into that collective creative impulse. What might happen if we entice hundreds, or even thousands, to make something? What magic might begin? What conversations might start?

In an essay for the online art zine Quodlibetica, “Project to Practice: Imagining Communities,” essayist and critic Christina Schmid wrote the following on the evolution of public art-making, and it reflects our hopes for this process:

“The goal is not a revolution but an evolution: a slow-moving suggestion of change, of possibilities for a ‘new normal,’ a different set of social facts, rather than a possibly painful collision.”

10 Years + Counting is decentralized, non-prescriptive, and encourages the innate creativity in all people without hierarchy or judgment. And although projects will be spread across the country, each individual, ad-hoc group, or institution will be connected to the project and to each other through interactive mapping on the website. 10YAC hopes to illuminate one of this most important and contentious issue by connecting people via the related practices of reflection and creation.

I call it seed planting.

We don’t know yet what we will harvest. Ours is a practice built on faith and the belief that the process is as, or even more important than the outcome. We will be out there — encouraging, cajoling, and then letting go. We are called to action, to play a part, however modest, in creating a new day. We hope to stoke the collective imagination and then stand back and watch sparks fly.

I’ll end with an excerpted passage from John Berger’s brief and poignant essay “Miners.” Written in response to the cause of striking miners in England, facing violent repression, he brilliantly articulates my conviction about the power of creative practice:

“I would shield such a hero (miner) to my fullest capacity. Yet, if, during the time I was sheltering him, he told me he liked drawing…or always wanted to paint…if this happened I think I’d say: Look, if you want to, it’s possible you may achieve what you are setting out to do another way…I can’t tell you what art does and how it does it, but I know that art has often judged the judges, pleaded revenge to the innocent and shown to the future what the past has suffered… it makes sense of what life’s brutalities cannot, a sense that unites us.”

My story began and, at least for now, ends with war. But within this gentle, bold, and inclusive practice, I am hopeful.

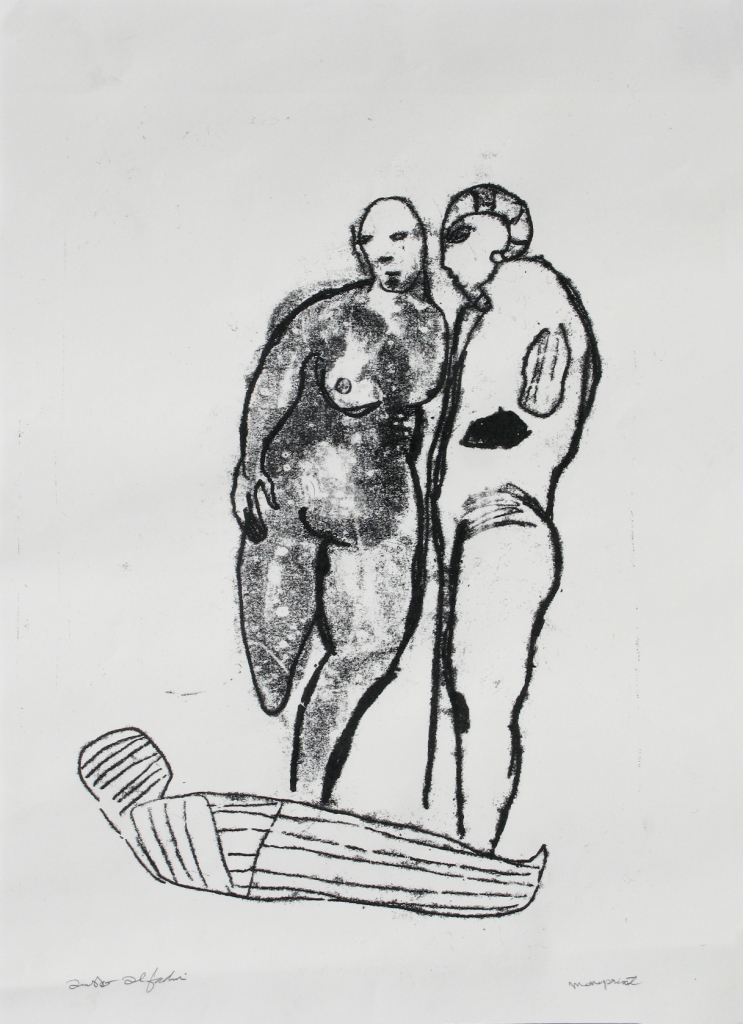

Related exhibition details: No Glory, a 10YAC exhibition co-curated by Camille Gage and her fellow 10YAC collaborator Susanne Slavick, opens this weekend at Form + Content Gallery in Minneapolis. There is an artists’ reception September 10 (7 – 9 pm), and a gallery talk September 18 (3 – 5 pm). The exhibition will be on view from September 8 – October 1, 2011. For more information about the exhibition, which features the work of some of the artists in the 10YAC online gallery, visit www.formandcontent.org. For more information on the national project referenced in the essay, visit www.10yearsandcounting.org.