A Braided History in a Time of Resistance

Arts writer Sheila Regan offers an embodied meditation on family, storytelling, and the strength and fragility of the body, following her experience with Kerel Kroul’s exhibition at the Rochester Art Center.

As I walked across Rochester, I felt bemused by the atmosphere created by having one of the world’s most prestigious, and expensive, hospitals plopped down into a small Midwestern city. It felt like wandering through a weird utopian health spa bubble. Everything looked vaguely like an alumni magazine where nobody smoked, and every restaurant contains nutritional information on their menus, including Denny’s.

I found some solace when I entered into Keren Kroul’s lovely exhibit, Topographies of Loss & Longing. Honestly, I was feeling unhinged and thwarted, and there was a calming nourishment I felt amidst Kroul’s artworks.

The central piece of the show was a large hanging installation, containing multiple layers of cut-out paper. The delicate shapes mirrored the geometric node formations Kroul often has used in her watercolor works. Kroul’s gravitation toward watercolor and paper reveals a sense of fragility. These are materials that could so easily be ripped or torn. In fact, the tiny tears in the sheets added to the work’s feathery texture. Kroul didn’t let the paper’s lack of strength stop her from manipulating it into web-like shapes that mirrored the dense intricacy of her watercolor patterns, where she had added colors layer by layer with tiny brushes.

The hanging piece was positioned in the gallery to soak in the light from the large windows facing the outside. I stood with my back against the window, the afternoon sun warming my neck. The intricately cut sheets cascaded down from the ceiling, as if they were a waterfall of light. The urge to touch these pieces almost overpowered me. I wanted to peek through the layers, but the work had a surprising opacity.

I had to walk around the white sheets to experience the art on the other side. It was as if the physical terrain of the gallery intentionally created an awareness of embodiment. My body moved through the gallery’s terrain, stirring thoughts and memories. The floor pattern of that path became a part of the work, a gesture that suggested a connection between one’s body and the land beneath us.

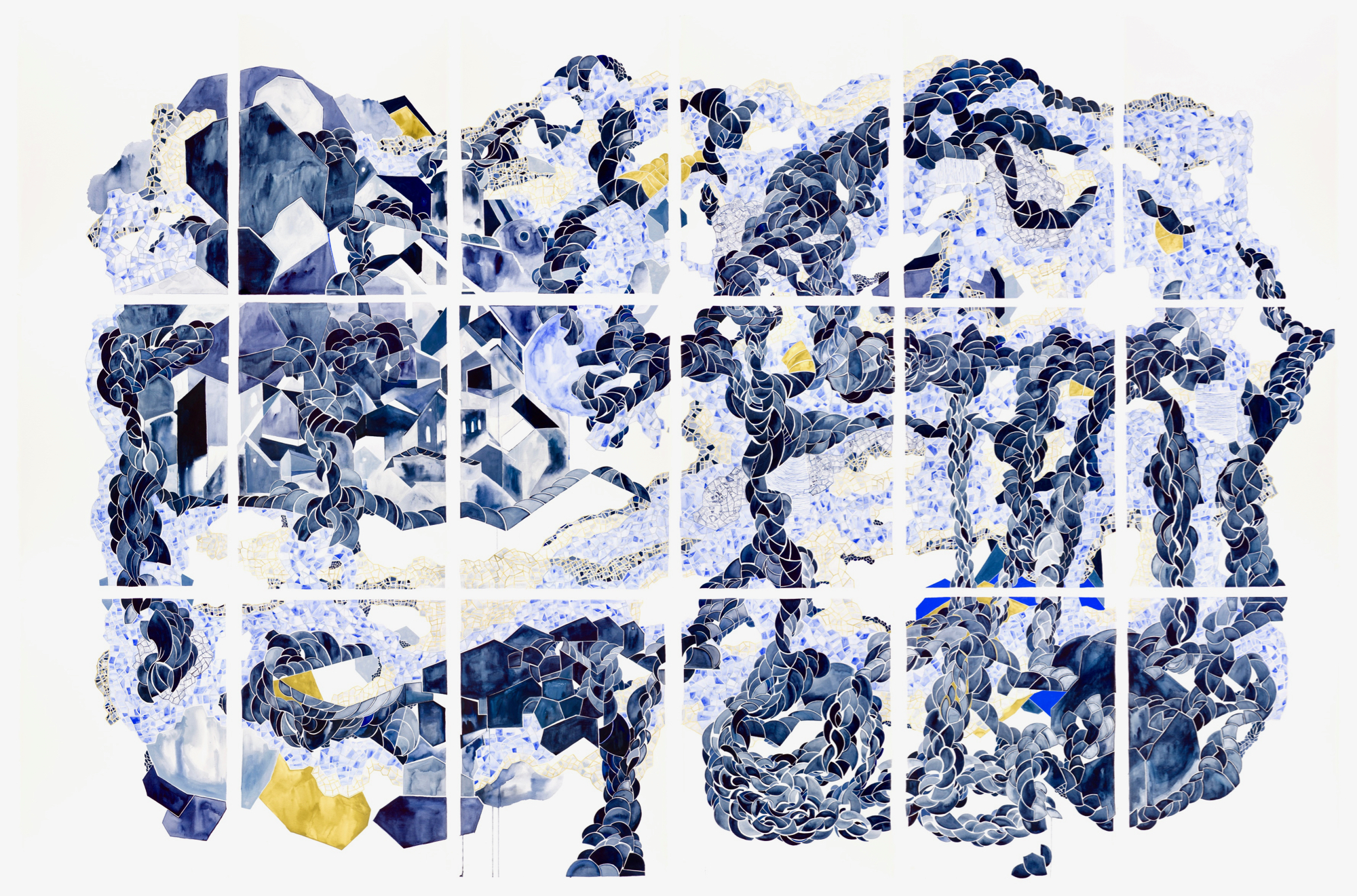

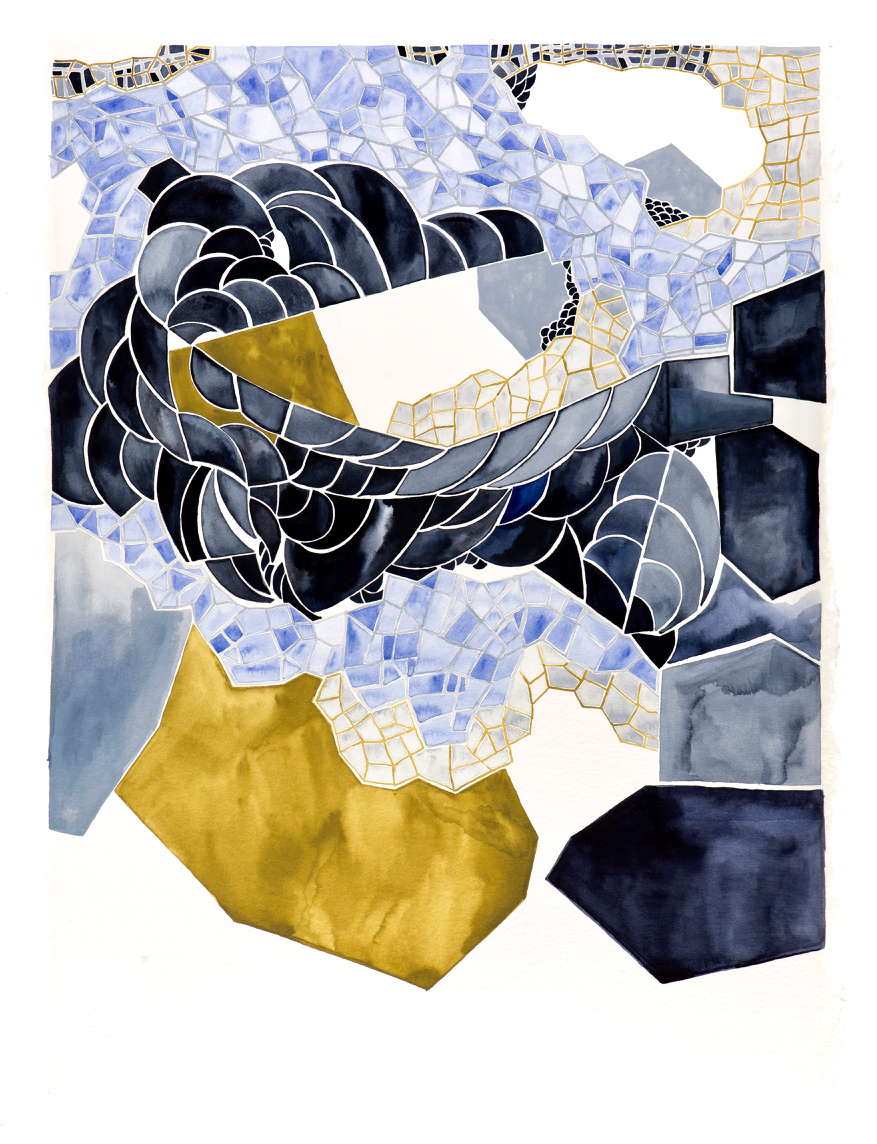

The 18-section watercolor piece on the back wall mirrored that contact with the ground, with the earth. Abstract villages of geometric forms floated on top of cloud-like woven braids. Engaging with this work was like wandering through a dream-like landscape, one with hidden stories and histories that poke through the surface. The work had a vertical movement, taking the eye up and down what seemed like mountains, with tiny portals opening up into far-away, faint realms.

“The physical object of the braids became transformed into a kind of pathway… The memory itself became a tool for searching, leading the viewer on their own journey into past histories.”

When I first looked at the work, I saw intestines, which makes sense in the context of a piece about memory—because our guts are literally our bodies’ second brains. Scientists have recently discovered that our guts have a mind of their own. Inside of the alimentary canal lie about 100 million neurons, which help not only with the digestive processes of our bodies, but with emotions as well. The old saying that you should trust your gut isn’t far from the truth. Our innards hold emotional truths and a window into our innermost selves. I’m convinced that’s where our deepest memories lie, and our truest emotions. Kroul’s geodesic textures and looping trajectories created abstract landscapes that evoked both the natural world and the cells that make up human life.

Kroul, who was born in Israel and grew up in Mexico and Costa Rica, has a complex back story. Israeli on her mother’s side and Argentine on her father’s, she grew up speaking Spanish and Hebrew at home, and English at school. Her grandmother, who was a twin, escaped the Holocaust, though her grandmother’s sister did not survive. Throughout Kroul’s grandmother’s life, she carried the braids of her sister with her in a wrapped piece of cloth, and eventually was buried with them. Those braids act as the formative building block for the piece, wrapping terrain and memory with a love that’s deep and impenetrable.

Kroul’s watercolor process involves taking a fragmented memory—in this case the braids her grandmother carried with her to remind her of her sister—and layering them in an enmeshed knot. The physical object of the braids became transformed into a kind of pathway, making its way through a vertical map. The memory itself became a tool for searching, leading the viewer on their own journey into past histories.

I found myself entering a collaboration with Kroul as I viewed her work. The afternoon I stood in the gallery, I had just spent the night on a cot at the hospital while my partner awaited surgery. The day before, I had made the drive down 52, the golden fields rolling past my car window. My own personal story at that moment met the artist’s, because of the open and enveloping narrative her work summons. I had my own need for healing on that particular day, and I found solace in the nurturing quality of the artist’s storytelling.

Though Kroul’s work is personal, as it draws on experiences of her own family, it’s also inherently political, given our current climate. With the rise of neo-Nazi and alt-right groups both denying the Holocaust’s existence and spewing hate against both Jews and other anyone deemed “other”, Kroul’s reference to her family’s history in the Holocaust offers a quiet hum of resistance.

Kroul’s inquiry into what home means, and what identity means, feels particularly relevant to our current crisis. We are in a moment where everyone, particularly artists, are called to engage in political realms. And yes, that means taking up the fight outwardly, but also requires an inward search of ways we hold power and privilege.

I tell you of my experience of Kroul’s work not as some omnipotent observer, critiquing art in a vacuum, but through my own experiences and my own body. I tell you all of this as a white, nearly middle-aged woman, born of a certain privilege, with hurts and sorrows and faults just like anyone else. I tell you these things because we must tell each other these things: We must say who we are and where we came from, and keep saying it. Simply engaging in truth-telling has become an act of resistance.

With the right-wing narrative about what it means to be a “real” American becoming narrower and narrower, it is through disparate stories, backgrounds and experiences that we create a richer understanding of humanity. It’s the role our institutions, like the Rochester Art Center, to continue to give a platform to a diversity of voices. As a woman, and a person of Jewish identity, Kroul navigates topics of personal and family narrative compellingly, and with nuance.

The paper-thin logic of fear-mongering rhetoric falls apart in the face of the dense and rich histories of the many peoples that walk this earth. Our memories passed from one generation to another bridge cultures and difference. Defying hate doesn’t take guns or weapons. Instead, our stories ultimately wash away ignorance. Sometimes a physical object, held onto for decades as a reminder of our loved ones’ strength, lifts us into a mountain of resistance.

This article was commissioned and developed as part of a series by guest editor Jordan Rosenow.