From Sandman to Star Trek to Sammy the Mouse

Writer Britt Aamodt takes stock of Minnesota's unsung wealth of notable cartoonists and comics artists working in every aspect of the industry, from the superhero staples of the genre to groundbreaking underground publications and web strips.

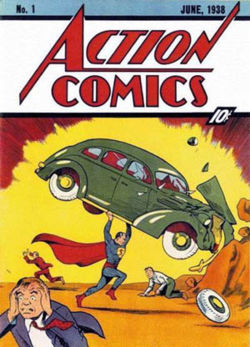

IF YOU’RE OFFERING A SURVEY OF MINNESOTA CARTOONISTS, you have to, first, mention that the Twin Cities ranks fifth in the nation for the number of resident cartoonists (and then follow that claim with a disclaimer that the above ranking is anecdotal at best). Of course, you’d also want to dust off your pop cultural histories so you could detail the genesis of the comic book form—which begins with ACTION COMICS No. 1, appearing in June 1938 to introduce Superman to a Depression-era America hungry for escapism. But it turns out that factoid, too, is debatable, with a number of collectors and cartoonists placing the origin of comic books at other times and in other publications.

So much for a definitive accounting of the history of comic books. And we haven’t even broached the subject of the production of comic art in Minnesota yet. You see, for all the hype surrounding comic-book-turned-movie blockbusters, the art of comics is relatively young, and it’s nursing a chip on its shoulder the size of Mount Everest (which, by any standard, is a hefty piece of real estate). But for all of you who get twitchy at the lack of critical respect shown to comics, consider this: When was the last time someone wrapped your birthday gift in a numbered Picasso print? Put another way, does anyone think twice when lining the kennel with Sally Forth and Dilbert?

From their inception, the funnies were meant to be read and then disposed of. And like their ancestor, the strip, early comic books were printed on a paper stock that, if it didn’t say “throw me,” hardly asserted its place on the shelf alongside Shakespeare and Nancy Drew. As arts journalist Roger Sabin points out in Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels (Phaidon Press, 1996): “Throughout their history [comics] have been perceived as intrinsically ‘commercial,’ mass-produced for the lowest-common-denominator audience, and therefore automatically outside notions of artistic credibility.”

But even so, you can understand the chip. Because whatever else they are, comics—whether you’re talking strips, comic books, graphic novels, minicomics, or web comics—are art, and a special art form at that (a point to which the sheer volume of ink spilled by its passionate defenders in recent years will attest). Hampered by their ephemeral nature and subsequent lack of credibility, comics have only recently begun to attract the kind of critical and historical documentation assumed in other art forms.

Getting back to Minnesota: there is no definitive history of the local scene, but these days it seems you can’t turn a corner without bumping into a cartoonist. So, perhaps Minneapolis artist Dan Klonowski (a.k.a., Danno, a.k.a., Dank) is onto something when he cites a comicsreporter.com article placing the Twin Cites fifth on a list of American cities with the most cartoonists. And his pal, comics artist Steve Stwalley, isn’t far off either, describing this diverse group of Minnesota artists as having a lot of POW! behind their creative punch.

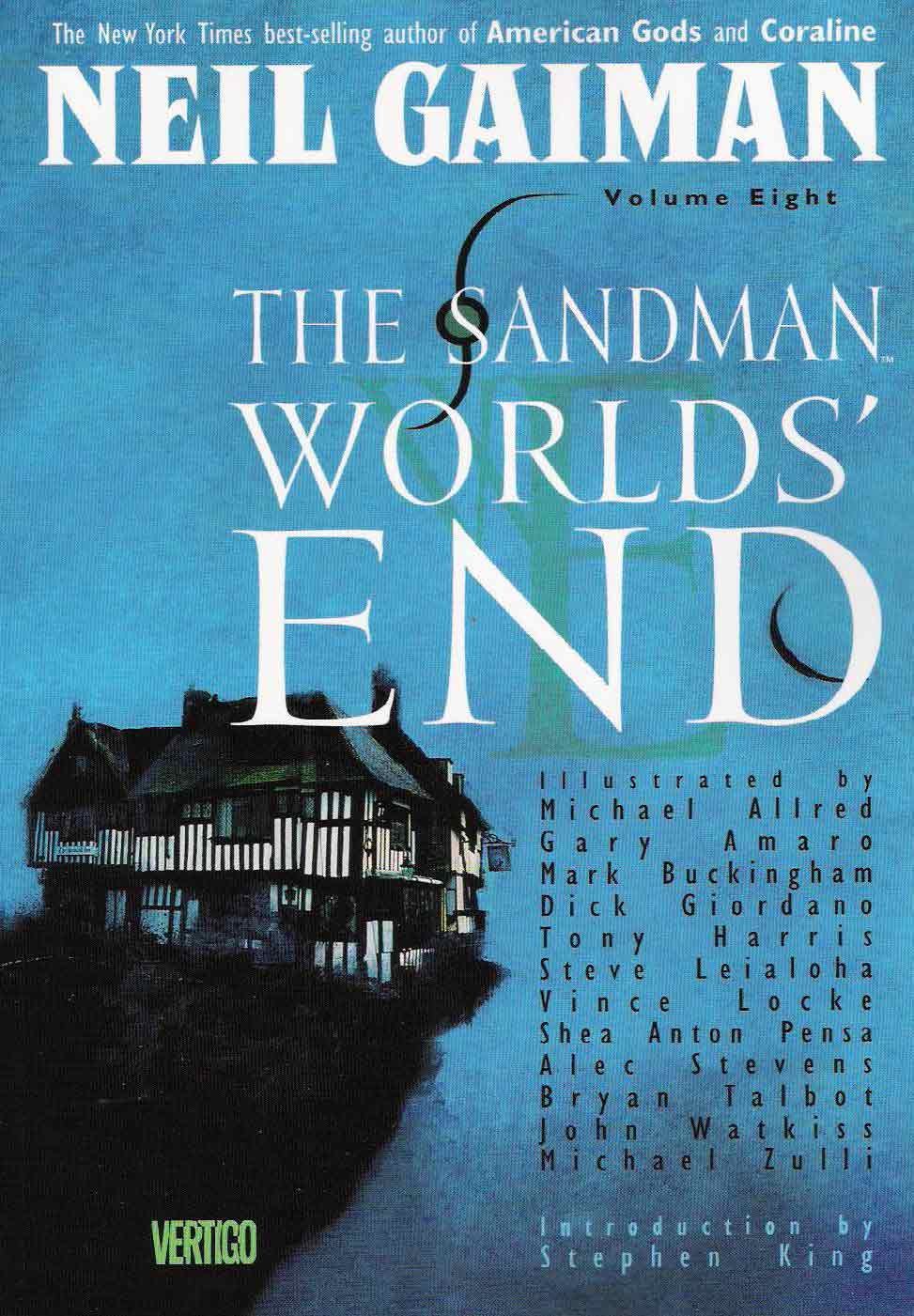

Dream Writer: Neil Gaiman

Probably the most famous Minnesota cartoonist is not a Minnesotan at all (because he’s a god), but a transplanted Brit; and though biographies often locate his home in Minnesota, it’s actually across the border, in Wisconsin. The artist in question, Neil Gaiman (author of the Sandman comics), is not a cartoonist at all, per se (though the cartoonists interviewed for this article claim he has a fair hand at drawing). Even so, his name pops up a lot in conversations with local cartoonists. For one thing, they all seem to have been over to his house at one time or another. (Maybe it’s the appetizers.) For another, Gaiman is just one of those guys whose work turns up on numerous best-of lists. You can’t not mention him if you’re talking about significant comics artists.

Gaiman’s Sandman series, first appearing in 1988, mines rich veins of mythology, folklore, literature, and history for a storyline nominally belonging to Sandman, the “Master of Dreams,” yet which also captures a growing list of supporting characters in its complex narrative web. Gaiman’s literary style has attracted new fans to the medium and has spun off more than one related series following the exploits of secondary Sandman characters.

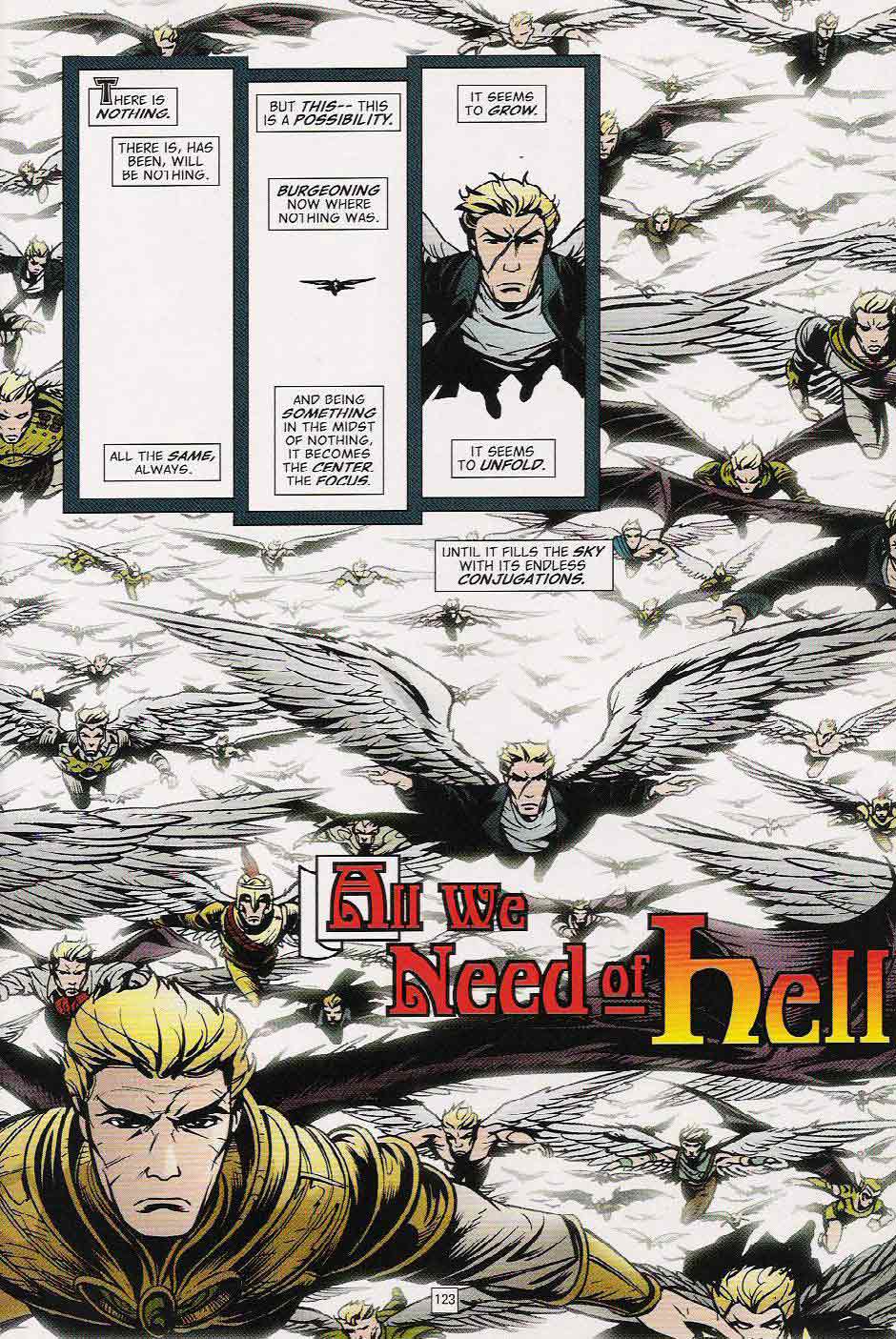

The Lightbringer: Peter Gross

One of those successful Sandman spinoffs is Lucifer. Written by Mike Carey, Lucifer was penciled and inked by native Minnesotan Peter Gross, who shares a classy old house with artist wife Jeanne McGee in Southeast Minneapolis. (McGee too has dipped her toes in comic book waters. She colored the miniseries Chosen.)

Gross calls his comic book work “mainstream,” which means his art appears in titles put out by some of comic book publishing’s big hitters: DC Comics, Marvel and Dark Horse. In the industry, “mainstream” also tends to refer to superhero comics. But with the shifting demographics of comic book readers and the burgeoning influence of underground comics (not to mention Harvey Pekar‘s success with quotidian themes in American Splendor), the big hitters have split off new superhero-less lines. Vertigo, DC’s line of mature comics, “has been called the HBO of comics because of its emphasis on story,” says Gross. Lucifer and Books of Magic, Gross’ series, are published by Vertigo.

“In comics, drawing is not the most important thing. There are a lot of artists, especially in independent stuff, who draw horribly. But they draw consistently and they know how to tell a story,” he explains. Gross, who is also one of the original instructors in the Minneapolis College of Art and Design‘s comic art program, says further: “I always try to teach students about storytelling. I figure they’re going to learn how to draw when they do. But to get them thinking about storytelling—that’s a huge step.”

A New Frontier: Gordon Purcell

If you’ve been tuned into comics lately, you’ve probably noticed another trend—an influx within the genre of TV show-spawned comics series. Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, and The Ghost Whisperer come to mind. Actually, licensed comics aren’t new, says Gordon Purcell, who has been penciling Star Trek comics for years. “Jackie Gleason and Lucy had their own comics,” says Purcell. “The idea behind licensed comics is that people who watch the shows want more. And this is a way to give it to them. I can draw William Shatner as a 35-year-old Captain Kirk where he’s thin and nice-looking and fit. They can’t do that in a movie.”

Purcell, who works from his home in Plymouth, has moved in and out of the series as the license has bumped from Gold Key to Marvel to DC to Malibu to Marvel again. IDW Publishing currently holds the show’s license, but even though other artists have worked on Star Trek, Purcell’s name and art are well-known to fans.

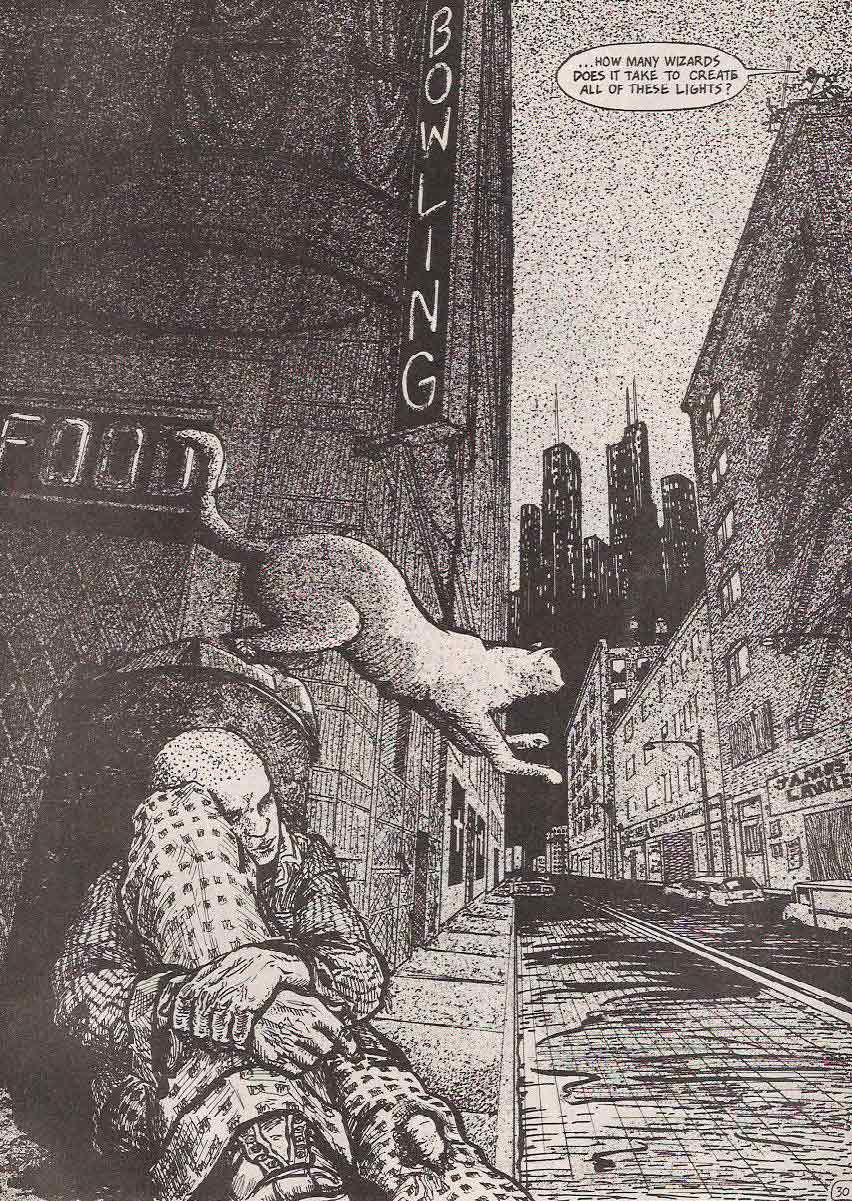

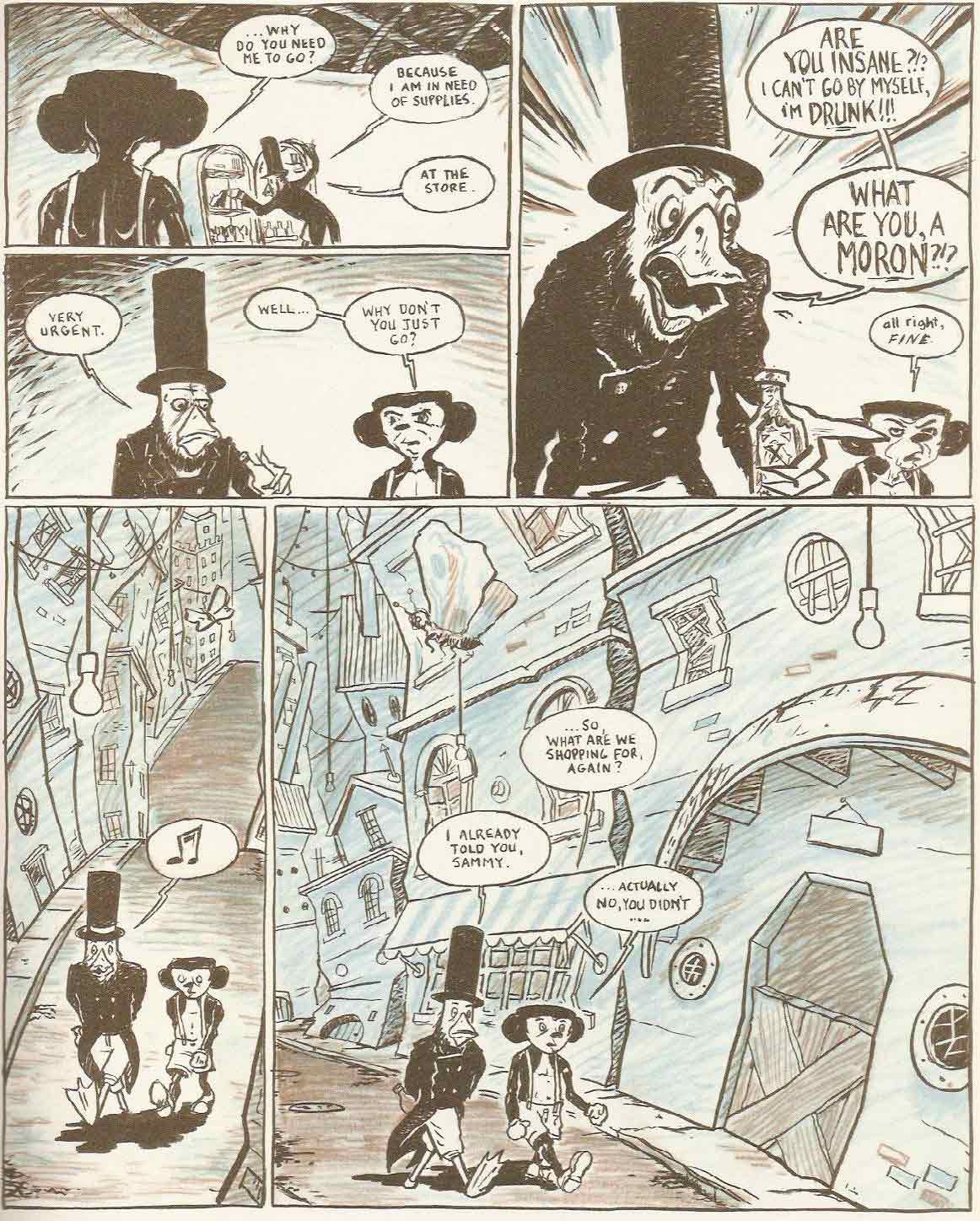

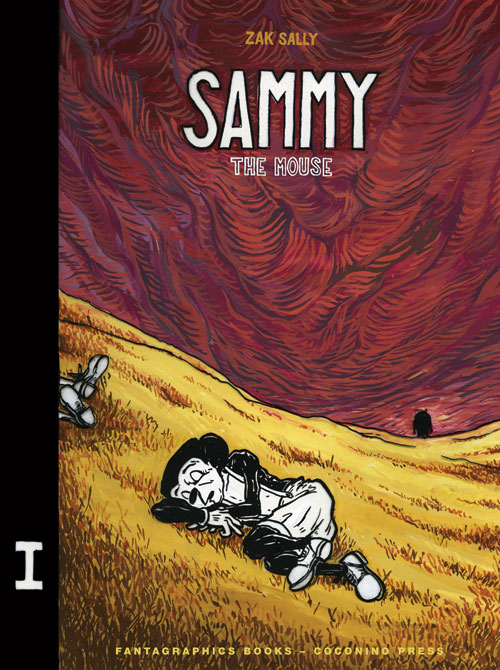

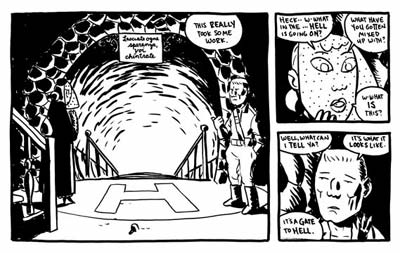

By Hand: Zak Sally

For 12 years, Zak Sally was the bassist for Low. Not a bad gig, by any account. “That’s when I learned you could make a living from art,” says Sally. In one of those moves that make for a good story, but only after the tough-decision making is done, Sally exited the music scene and turned to comics a few years back.

“I was leaving Low, and I sat down with Eric Reynolds [from Fantagraphics],” recalls Sally. “I said, ‘I need you to tell me the honest truth. Can a person make a living at comics?’ And he was, like, ‘No.'” It was hardly a rallying cry, but Sally took the leap, regardless, and has come out the other side with three installments of his minicomic The Recidivist and Sammy the Mouse #1, published by Fantagraphics in 2007; and he has a second volume due this summer. He has also formed his own publishing company, La Mano 21.

Sally falls on the other side of the blurred line dividing comics into mainstream and underground or “indie” publications—a catch-all label for artistic styles, content, and publishing models not typically covered by major publishers. Think Robert Crumb in the ’60s or, more recently, Dan Clowes (Ghostworld).

Separated at Birth: The Cannon Non-Brothers

Oddly enough, people assume cartoonists Zander and Kevin Cannon are brothers. It’s not an unfounded assumption: they’re both graduates of Grinnell College and they similarly sport beards, spectacles, and the name Cannon. They also share ownership of Big Time Attic, an illustration and comics firm in Northeast Minneapolis. Even if they’re not brothers, the two Cannons share a singular talent for diversification: mainstream comics, commercial illustration, self-published minicomics and web comics, and they are on the ground floor of a new line of comic book-styled textbooks. METRO Magazine named their Big Time Attic blog the “Best Comics Blog in the Twin Cities”. (“Out of how many?” notes Zander, the wry elder Cannon.) The duo has also used the web to publish their comics: Zander’s Heck and The Replacement God and Kevin’s Far Arden.

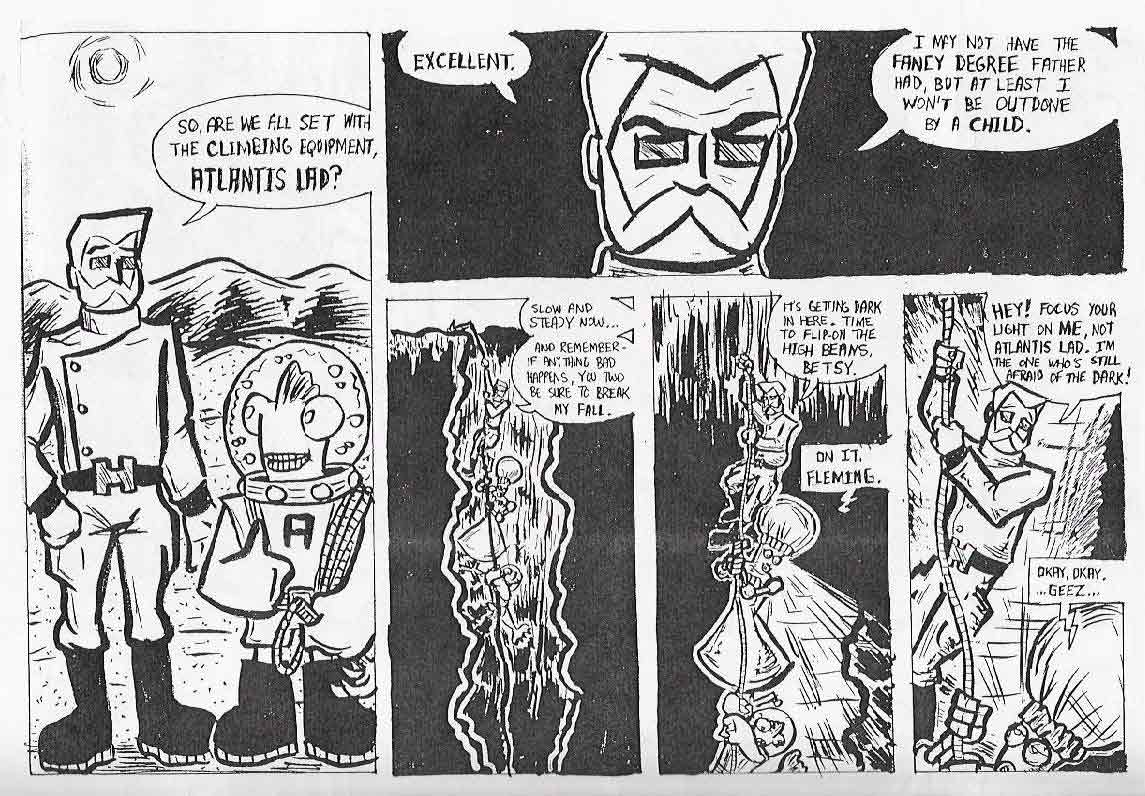

Conspiracy Afoot: Steve Stwalley and Danno

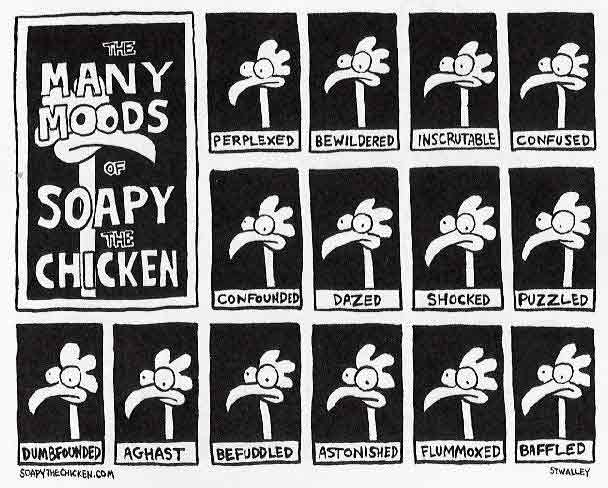

The rule of indie comics is that there are no rules. And you don’t get more indie than a Kinko’s copy-cut ‘zine, folded and stapled down the middle. Just last month, in early May at Altered Aesthetics in Northeast Minneapolis, fifty of Minnesota’s indie cartoonists convened for the Lutefisk Sushi show and publication party. The show, now in its third year, is the brainchild of Steve Stwalley, cartoonist of the online strip Soapy the Chicken and founder of the Cartoonist Conspiracy. The purpose of the Conspiracy, which has spawned cells outside the Twin Cities, is “to develop a community of cartoonists at all levels to share, meet, and collaborate,” says Danno, who is a longtime member with work both in the show and in its companion publication, the minicomics Sushi box set.

“We have a wide variety of influences,” says Stwalley. “There are some who do superheroes. Certainly, a lot of us have also been inspired by underground comics. But there’s a real focus locally on personal expression.”

Danno sums up the no-rules ethos of the group: “It’s really about creating whatever weird story comes to mind.”

And they do—with stories about Arctic pirates, colonialist explorers, sad sacks and regular dudes playing out their lives one panel at a time, just like their creators, who are too many and too gifted to get their due in a single article. For all the artists mentioned above—Sam Hiti, Dan Jurgens, Chris Monroe, Tim Sievert, Will Dinski and Vincent Stall to name still a few more—there are dozens more living and working in Minnesota, sending ripples into the vaster comics universe. Who knows? Maybe the next American Splendor, Crow, or Road to Perdition will bear the legend “Made in Minnesota.”

Related Links and Resources

• Neil Gaiman’s website

Gaiman’s website provides an author bibliography, information on forthcoming projects and a blog that seems to follow the author wherever he goes.

• Peter Gross’ website

Gross’ website provides images of his original panel illustrations.

Not solely a Star Trek artist, Purcell has worked on a number of comic properties, including the Hulk, X-Files, Kolchak the Night Stalker and Superman.

• Zak Sally’s website

Sally’s site offers information on the cartoonists adventures in the comics world and information on cartoonists published by La Mano 21.

• Big Time Attic

Zander and Kevin Cannon’s website and blog feature links to the cartoonists’ ongoing web comics, tips on craft and a page of unusual, not-yet-invented inventions.

• Steve Stwalley’s website

Check out Stwalley’s online strip Soapy the Chicken here. Or venture to http://www.stwallskull.com for more of Stwalley’s work.

• Danno’s website

Danno posts online comics, including Manly Tales of Cowardice, on his Staple Genius website.

• Cartoonist Conspiracy website

The Cartoonist Conspiracy website provides information on membership and an updated list of events, including the first Thursday of every month comic jams at Diamonds Coffee in Northeast Minneapolis.

About the author: Britt Aamodt is a freelance writer living in Minneapolis. She loves the arts, meeting new people, and grocery shopping.