When Pigs Fly: Eric Dubnicka

Ken Bloom, the director of the Tweed Museum of Art at University of Minnesota-Duluth, recently guest-curated a show at the Duluth Art Institute. Here's his take on what he saw in Eric Dubnicka's work.

First impressions are said to be everlasting but they mislead: what seems opaque can later gain transparency. You may need this second impression to pierce the density of Eric Dubnicka’s new work. Character, mystery, and motive reward your gaze. The work’s readability is inversely proportional to the degree that its form and style represent conventional aesthetics. Abstraction used to present this conundrum, but audiences have learned to recognize that all images derived from the imagination present an abstraction of sorts, and that abstract art per se is a representation of realities of feeling.

When form-as-gesture acquired mainstream audience acceptance, abstraction faced a crisis. Artists responded by attempts at expanding the range of form and subject, also employing non-art materials, insinuating samplings of vernacular culture while trying to confound the act of depiction itself. Artists discovered that, by allowing chance and by channeling inchoate forces that emanate from their sensory and psychic environment, they could reach a more accurate representation of ideas in their work. The product would, in theory, manifest this metaphysics in whatever form might be discovered along the way.

Eric Dubnicka has quick-stepped into a world of artistic vision that grew out of action painting’s spontaneity. Though he inclines toward the self-expressive marks typical of Abstract Expressionist artists such as Willem De Kooning and Jackson Pollock, Dubnicka does not, as did the action painters, use the canvas as a self-biographical arena, wherein the event of painting is itself the sign of its own meaning.

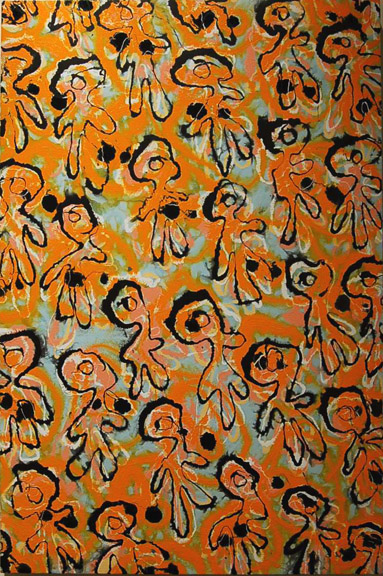

Instead, Dubnicka’s work reflects the attention he paid to Neo-Expressionists such as A.R. Penck, Nouveau Fauves such as Jonathan Borofsky, graffiti artists such as Jean Michel Basquiat and David Wojnarowicz. Art-world tropes such as dripping paint, popular culture iconography, graphic-narrative style, primitive mark-making, and “Bad Painting” reveal a commitment to allowing the work to develop outside of conventional formalist pictorial controls. The result is a material naturalism — the work evolves according to properties of materials used, and according to the spirit of the mind while it makes choices among possible actions. Such actions reflect abandon, yet intend to attain accurate representation — that is, they embrace myriad conflicting forces typical of essential human struggles.

We are each surrounded by the unseen. Forces beyond our control press from within and without, testing our balance, challenging our ability to cope. Each of us seeks equilibrium; each of us unearth demons, ghastly and immutable distortions of our subconscious selves. Such fear attributes breathtaking powers to a chimera. Left undefended, the truths upon which one’s confidence is founded suffer. The sense of self turns transparent; the ground upon which we stand depends on certainties — now diminished by contingency. Such is the human condition that teaches us of what material consciousness is made.

In the face of the perceived need for artists to engage political, social, and emotional questions, to provide guidance in a contingent and ambiguous world, formalist strategies have not been embraced by wide audiences. But artists resist such pressures; the artist has a nature that continues to seek individuation and to chafe at the seams of external systems of control. According to the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, “We have art in order not to die of the truth.” But this is a truth of contradiction: the victim is a perpetrator and vice versa; psychologically and pictorially the foreground is pushed to the rear without horizon; the middle is polarized, and the unseen is felt as an assault.

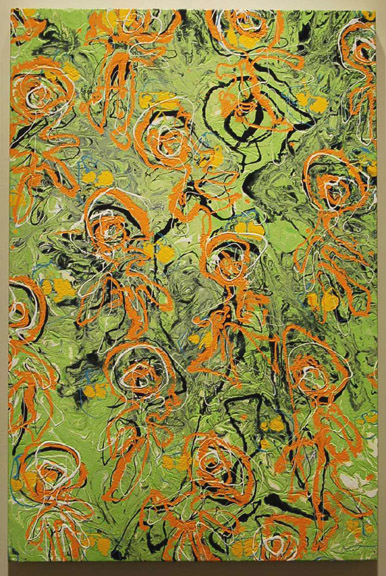

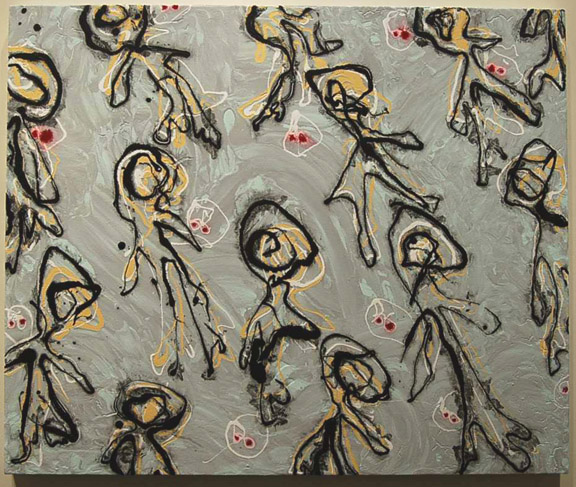

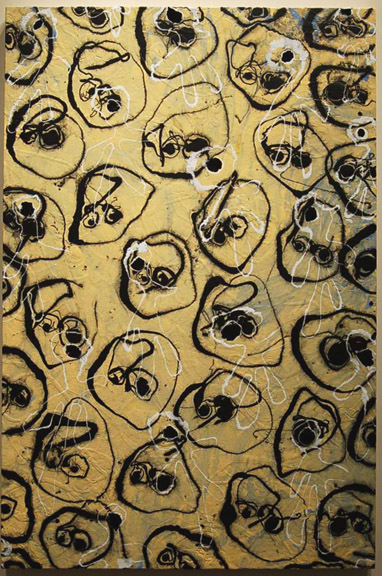

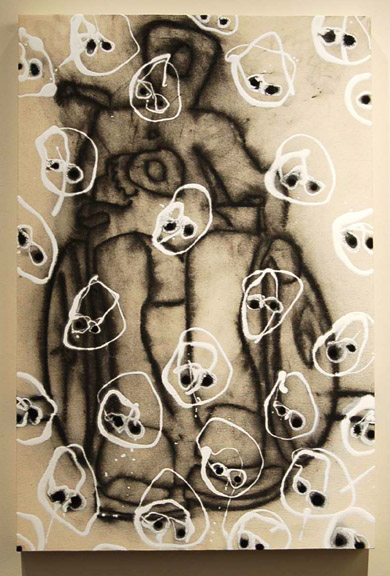

Dubnicka’s paintings trade on the irrational. Space is generally compressed and distorted, often with no polar orientation. Up can be down, and vice versa. The view from the onlooker’s perspective could be from above, analogous to the view through a microscope where directionality is rationalized as a dimension of depth. One discovers layered fields of forms, in repetitious hoards, as bacteria would appear. When the forms appear as figures, they are distressed, blind, asexual and porous. Where a body seems to form, its head is a hole. The effect is hallucinatory; the pictorial syntax is one of mutation.

Dubnicka does throw us an anchor to keep us from drifting too far afield. His drawing style is fluid, but rational. Depictions reveal an interest in replication, seriality, even satire. Repeating form suggests meaning in that form. Dubnicka’s absurd rendering of brainless beings suggests a symbolism of blind adherences. We begin to see a moral thrust in the artist’s thinking, as well as a rudimentary and somewhat cranky sense of allegory.

We see reflected in these fictional figures the roots of actions within our own arena. Are we accused? Is Dubnicka’s exasperation with us or just with others’ human folly? Through what line of thinking has the artist drawn us into such dark observations? Again, answers may be found in tradition. Dubnicka is expanding on a history of artists crying out into a world that cannot feel as they do, and cannot see as they do. Confronting the audience with exaggerations, Francisco Goya’s Los Capricios, Edvard Munch’s Scream, Diane Arbus’ Boy with Grenade come to mind as underlining Dubnicka’s contentions.

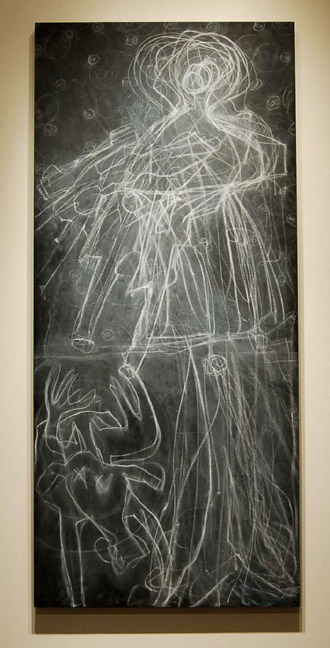

At one end of this gallery installation is a single painting depicting a wheel-chaired individual holding a gun while peering at you through a screen of faces. This guilty yet avenging angel of the underclass allows no escape from judgment; you are witness to what appears a paranoiac episode of a disabled psychotic. He’s pointing your way. On second glance you may notice that this work hangs perpendicular to a monumental canvas wherein thousands of figures amass on a hill, revealing a singularity in their aggregation. A ghostlike figure forms by accumulation within the mass. It is a remarkably Boschian scene. This is humanity in its uphill struggle. This is humanity seeking salvation.

The effect is a reminder to us of thematic desperation periodically surging through art and literature of past ages referring to the fall of man due to moral decline. Dubnicka’s prophetic vision demonstrates a similarity in the dystopian facts of our postmodern age. His is a curiously millennial vision, almost biblical.

In the Book of Revelation John prophesized the fantastic and seemingly impossible fall of Rome and the coming of the new age symbolized by the skyward vision of the lamb. Dubnicka by contrast offers us an absurdist, somewhat ironic alternative vision of a world where pigs fly, the other side of John’s vision: his witness of the foreboding appearance of the beast.