Old Hand

John Orth is showing a retrospective of sculpture, drawings, and paintings at the Tweed Museum of Art, on the University of Minnesota campus in Duluth. The show is called Archetypes and Armatures, and its deeply pleasurable. (Through Nov. 18.)

It’s a surprise to come across sculptor John Orth’s work and realize what depths of time and attention have accumulated in it. He’s been working steadily for over 30 years, getting up in the morning and opening a sketchbook, planning work, traveling to the studio and building flasks and molds for casting, carving patterns, pouring iron, welding steel. He’s been thinking about the forms he makes, thinking about what he sees on the way to the shop, thinking about whether all this makes any sense. And steadily, surely, with a good eye and a lot of skill, he’s made work that reflects this constant practice of imbuing materials with intelligence.

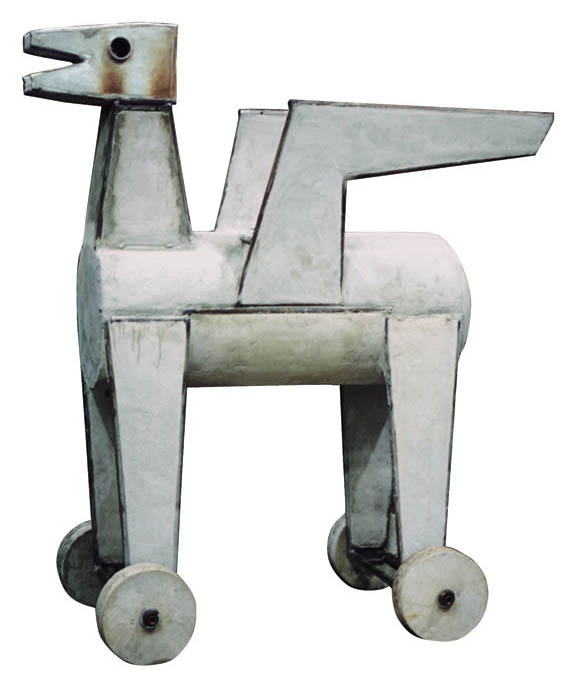

Peter Spooner, the curator of this show at the Tweed Museum in Duluth, understands the need to show Orth’s life and processes of thought. Fine cast iron sculptures like “Iron Fist” and “Zeus” are shown with wood assemblages that seem more temporary, and with pages from sketchbooks, small drawings, tentative ventures into trajectories that you see, later, in final form as sculptures.

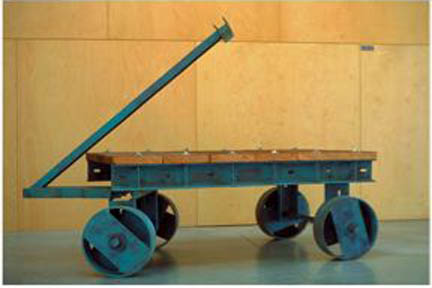

Orth also makes tools and studio furniture familiar to any sculptor: work carts, worktables, hoists—the stuff he needs in order to make his sculpture. But Orth makes them with an attention and care that’s rare—particularly the carts and wagons. Their foursquare forms turn into something significant, both hieratic and cute, ponderous and full of wit. It was a great idea to include them here.

Process—life process, work process, how things get thought, how they get made—is the real burden of this show. Spooner writes, in his essay, “Each work is a solution to the technical problems inherent in sculpture—how to cast, weld, bend, or shape it, along with a question that is key to the rugged look of his work—when and how to stop making it.” This seems precisely to the point, looking at the work: the objects and drawings are well done, full of energy, lively—but they would not be nearly as effective without their context of deep and embodied meditation on what it is to make things, what it is to make at all.

Three short videos with texts written by the artist push the emphasis on process further–the camera follows him in the course of working. These are amusing, but seem peripheral at the moment. It’s possible that he will find ways to incorporate them into the larger body of work more effectively.

You can read the influence of his teachers and mentors in Orth’s work. He’s studied with some of the past century’s most interesting artists, from painters Grace Hartigan and Jack Tworkov to sculptor Julius Schmidt. Abstraction and a kind of musical attitude to form held sway when these artists were in their heyday, and that tendency can still be seen in this show. It would look dated except for the incorporation of all these traces into a practice that in itself is a work of art. It gives the style new life.

The small drawings and sketchbook pages, work notes and typewritten or drawn texts, are some of the best work here. Motifs like the horned man remind us that there’s a protagonist, and invite us to take his place.

And all the work swirls around the cast iron, which, true to its weight, does provide the gravitas at the middle of the show, and is the medium for which many of the wooden patterns and flasks are made. A cast-iron fist at the entrance to the show (which can be worn—slipped over a hand which grips an internal handle!) is oddly magnetic. That almost self-mocking reference to the power of the artist’s hand hovers over the rest of the show, over all the thousand traces of that hand, from the delicate lines of the watercolors to the careful wrapping of the string and rubber on some of the wooden forms, to the tight craft of the studio carts and hoists.

This isn’t a perfect show—some of the more literal figures, the female figures in particular, are less than inspired; a few of the assemblages fall over the provisional edge—but it’s testimony to a life that’s far from virtual, and imbued with an intelligent sensuality and material skill that’s rare and welcome.