Homecoming: T. L. Solien at Bockley

Mason Riddle reviews T. L. Solien Drawings: 1997-2003 at the Bockley Gallery, 2123 W 21st Street, Minneapolis. The show has been extended through June 2.

Ma

“My work represents the relationship between symbolic presentations of the Self and the existential framework in which the Self operates”

-T. L. Solien

Seeing T. L. Solien’s recent exhibition of mixed-media works on paper was something akin to being paid an unexpected visit by a long-lost friend, a welcomed homecoming where all is familiar yet somehow new. After a 10-year Twin-Cities hiatus, here were nine Solien drawings, each a tense psychological blend of recognizable images, oblique symbols, bold abstract forms and gestural markings. These works were complex, deeply personal and highly associative, classic Solien, allowing the viewer a toehold on meaning, but never passage over the threshold for clear understanding.

Solien’s work has always been autobiographical, dogging his Sturm-und-Drang experiences, which are rendered through fantasy figures from the Wizard of Oz, Walt Disney or other transient, make-believe environments. In his earlier work, he would assume different identities such as the Tin Man, a sympathetic character but yet one with no heart, or a tearful schoolboy wearing a pointed dunce cap. These caricatures would be combined with other images and symbols to make pictographics, uneasy psychological and emotional narratives.

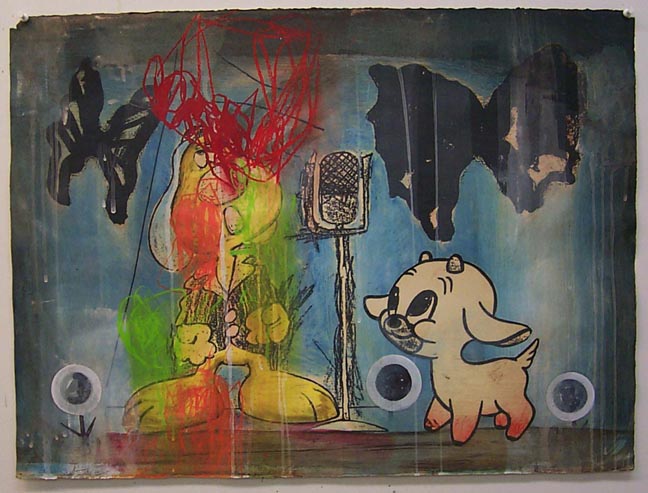

In the current offering, Solien’s work is no less oblique; perhaps it’s even more so. Over the last decade or more, a greater visual density of image and abstract form has informed his work, as these drawings, covering a seven-year period, confirm. Here, cartoon characters associated with Disney, comic books, or children’s literature serve as Solien’s alter ego. Bugs Bunny, Porky the Pig or one of the Seven Dwarfs are combined with other representational images such as a microphone, a falling oak leaf, a ship or a lighthouse, to construct a layered mélange of meaning. Images meld and collapse into each other, forming entirely new, eccentric figures. When they’re overlaid with abstract forms, passages of color, and animated markings, they recall a classic Surrealist mode of storytelling. Everything appears to be symbolic or a metaphor, yet the beckoning narrative is, ultimately, undecipherable.

The strongest works in the show are those with the most clarity of image, allowing the viewer a tangible point of entry into the work. For example, in “The Wayfarers” from 2003, a small simple boat, laden down with figures and objects, chugs downriver. Its inhabitants are a couple of bunnies, a black catlike figure, a disembodied eyeball, a cross-like mast with no sail, and a red oozing form of which Dali would approve. Is this Noah’s Ark or “The Heart of Darkness”? Does the black cat, the floating eyeball, or the actual voyage itself, signify Solien?

A more visually delicate work, “Lighthouse Keeper” from 1999, is equally seductive, with its subtle coloring and relative passivity. Here, a small lighthouse on a rock outcropping, a pair of (wedding?) bells tied with a bow, and a grid/window form crowd into the lower half of the drawing. Above, an eye bobs like a sentinel in an undefined space, along with other images (a monkey figure smoking a pipe?), abstract forms, and atmospheric markings. Of particular note is “Two Harbors,” from 2002, a sophisticated composition of image, form and color. A bit Picasso, a bit Magritte, here abstracted and unidentifiable images coalesce in a blue, room. Two smokestacks belch out dark smoke and Mickey Mouse hands wave good-bye.

As in all of Solien’s work, these drawings are deeply personal accounts about life events. These are dark stories, tales that border on discontent and failure, rarely happiness and success. There is no room for humor, only irony, and most of paintings seem to be bittersweet narrative at best. For nearly three decades, Solien has explored and analyzed every aspect of his life – marriage, family, religion, memory, and sexuality – adding, by twists and turns, new protagonists to his motley crew of characters. There is a power in the consistency of Solien’s vision. His investigations of Self have allowed him to develop an ever-evolving and identifiable iconography, a visual tenor and style that not only serves his own practice but also the viewer. We can count on not understanding Solien’s works; but we can also count on being engaged. In the end, we must ask what it means to explore such a solitary – even epic – path, where all roads lead, for better or for worse, back to Self?

There was a time when Solien’s paintings, prints and drawings were virtually everywhere – in galleries and museums here, in New York and Chicago, to mention just a few cities. While his exhibition history with the Glen Hanson Gallery in Minneapolis in the early 1980s was impressive, it was really the inclusion of his work in the 1983 Whitney Biennial that focused the world’s larger gaze on Solien’s aesthetic. Following shows at the American Center in Paris and in the Brooklyn Museum, New York, he was one of nine artists in Walker Art Center’s 1984 ground-breaking exhibition, Images and Impressions: Painters Who Print, which included such heavyweights as Francesco Clemente, Jörg Immendorff, and Susan Rothenberg.

In the late 1980s, he stepped out of the limelight, moving to Pelican Rapids, Minnesota, with his wife and children, to work. Ultimately feeling financial pressure, a peripatetic Solien eventually taught painting and drawing at several universities, including the University of Iowa, Montana State and Ohio State. Since 1997, he has been an Associate Professor of Art at University of Wisconsin- Madison.

Mason Riddle has written about T.L. Solien’s work for Artforum and Art Paper and she authored a catalogue essay on his work for a 1995 Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program show titled Bewildered Image2, which also included the work of Lance Kiland.