New Skins at the MIA: Painting in a Whole New World

In New Skins, Jim Denomies and Andrea Carlsons show at Minneapolis Institute of Arts, painting takes a new direction. Its an important show, and an immensely pleasurable one.

”New Skins” is big, in all ways. It’s an ambitious show that’s highly successful. Jim Denomie and Andrea Carlson both use their positions inside and outside the standard artworld to brilliant effect. The artists’ work is very different, but the pairing works. Carlson and Denomie are both of Anishinaabe ancestry, but more than that, they are fine artists with academic training and fully developed personal styles. They use their media in sophisticated ways, working out of both Euroamerican and native cultural traditions.

What was most instructive about this show to me was how rich the traditions of art are if they are approached not only from the inside, but with the perspective of someone who can both take a tradition and leave it—someone who can see it from inside and outside simultaneously. This eliminates stale strategies of quotation and irony, and opens up new potentials in the practice of painting. Both Carlson and Denomie are possessed of more than one tradition, and that seems to be a rich and liberating condition.

Denomie’s half of this show contains two bodies of work: the Renegades (a series that’s been developing over the past decade), and the Painting-a-Day series (which were painted during every day of 2005). They’re quite different, though lately they approach each other more nearly than they used to.

The Renegades are funny and angry paintings reminiscent, in their detailed wit, of Hogarth. Like the eighteenth-century artist, Denomie sees the cruelties of history and must laugh at them, because the alternative would be ungovernable rage. The earlier Renegade paintings often had a kind of unearthly beauty as well, particularly in the skies and sometimes the land itself, often represented as a body or bodies. The humor is in the terrible antics that humans get up to, under those luminous skies.

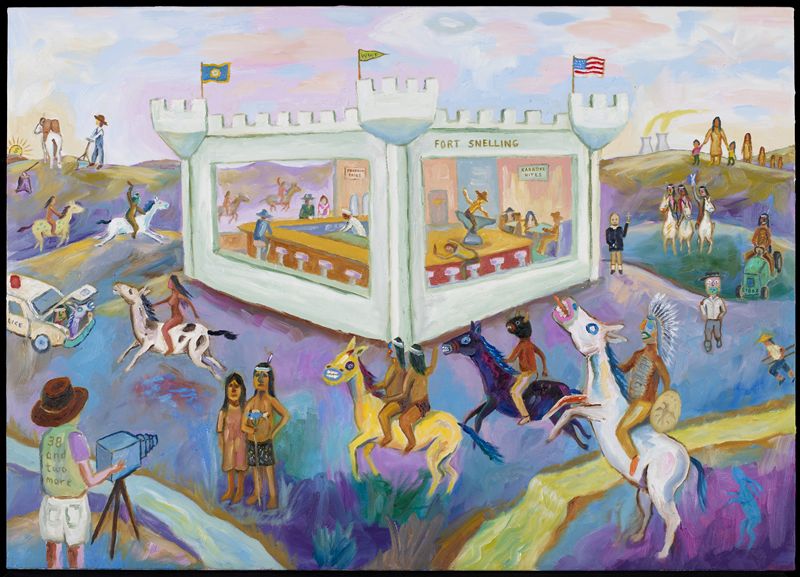

In Attack on the Fort Snelling Bar and Grill, beauty is not the point (even though it’s an exuberant field of paint, well handled). Humor and edge are there in force. It’s a story painting, and all its details have great twists—the patrons seen through the café windows quote Hopper’s famous Nighthawks; the bewildered farmer from Minnesota’s Great Seal is being mooned by an Indian on horseback; with bitter humor, an Indian (and his inseparable grinning horse!) peer out of the trunk of a police car. There are terrifying shape-shifters and goofballs alike in this work, an immense range of the characters found in the landscape between two cultures. Denomie’s wit has never been in better form.

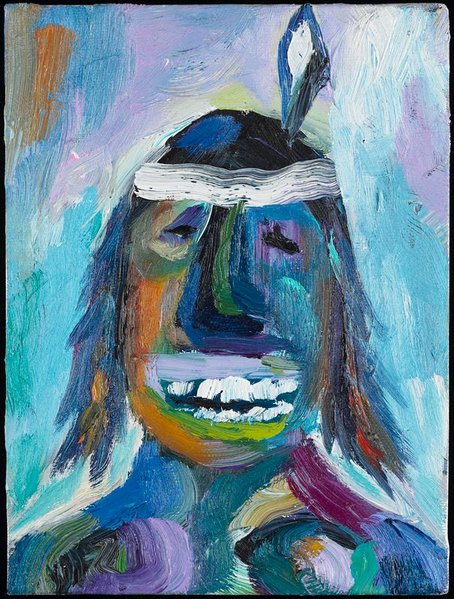

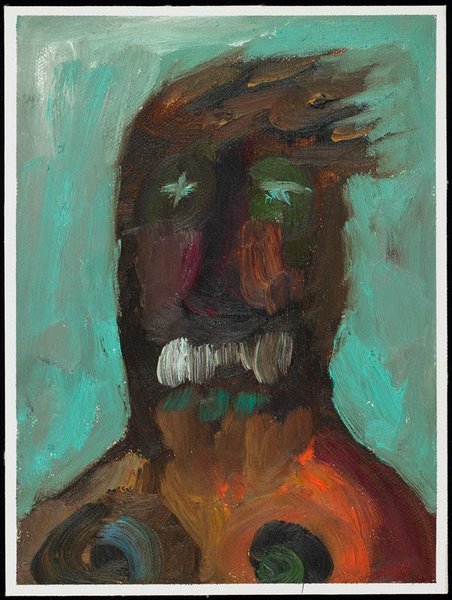

In the Painting-a-Day Series, the beauty and power of Denomie’s use of paint return. These are private works, and contain, in naked honesty, love and terror and bemusement; some are calm and lovely, some are deeply open and disturbing. All are worth seeing; the fact that there are hundreds, a whole year’s worth, mean you’ll need to spend some time.

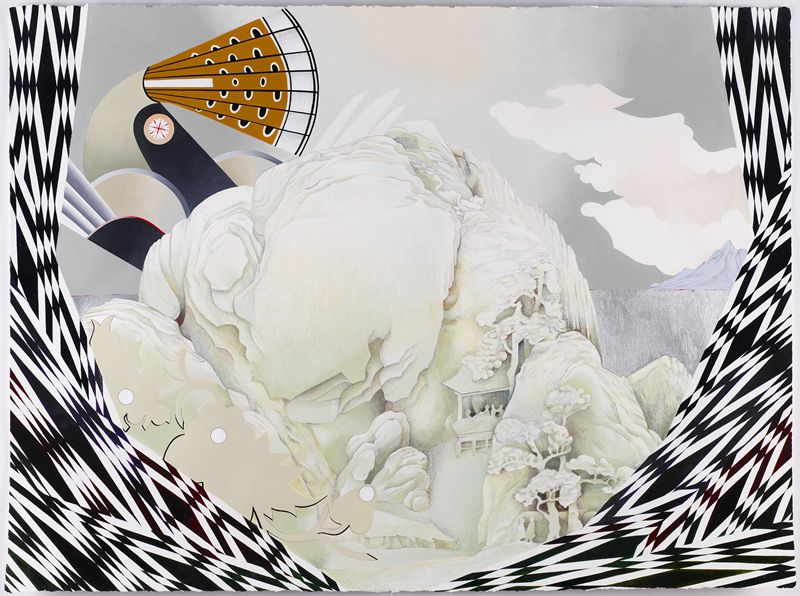

Carlson’s work here is also double—she has works on paper, and a new series painted on stretched beaver hides, which of course were the currency that first brought together European culture and Anishinaabe culture. The otherworldly landscapes in her work are clothed in resonant patterns; there’s elegant violence, sexiness, blood.

Carlson combines her Anishinaabe and Swedish heritage and her knowledge of art and cultural histories to construct a series of artifacts about artifacts—and about the conventional Western museum mindset. In some sense, by turning the art and artifacts of other peoples into mere aesthetic objects, we strip them of their power and of their ability to bring things about: connections, ideas, new forms of being. By imposing a museum context, we make things “ours,” not “theirs.” Carlson turns this dynamic inside out, with wit and ease and grace.

She’s incorporated many of the objects in the MIA’s collection into her own compositions, which are resonant with a use of form as real power, and with motifs from Anishinaabe story—a sort of museum as well, a house of cultural power. Wittily, this puts the MIA’s famous jade mountain or its dazzling decorative silver into her museum—which is located in a parallel world, a world not fully accessible to those not privy to its sources and its force. We can see the things there—are they sitting on a beach? Are they offerings to the dead?—and they’re beautiful, drawn with impeccable technique, hovering in a kind of everymans-land among cultures.

You must see this show. It points a new way to relate to art history—it turns it into art histories, and restores artists to their role as primary interpreters of art and these histories. There’s a great lightness and power to the humor in this work, which is deeply serious; and the sense of a sudden, and welcome, shift in perspective comes both a surprise and a relief.